Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Dialogue

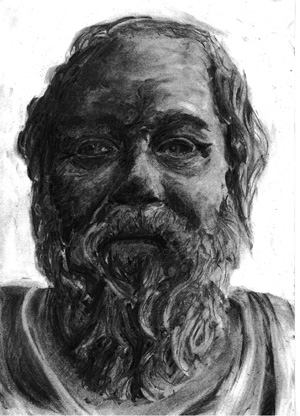

Socrates on Conservatism

Mordecai Roshwald imagines what the Athenian gadfly might have said.

(In this dialogue the writer has taken the philosophical licence of dispensing with the dimension of time, which otherwise led to blatant anachronisms. The dialogue tries to recapture the early Platonic, alias Socratic, manner and tenor of discussion, and so is an homage to an intellectual exercise which defies the vicissitudes of time in other ways.)

Constant: How good to see you, Socrates! I haven’t seen you for ages, ’though I frequently think of you. Where have you been these many days?

Socrates: As always, here, hanging around the shopping mall. Not that I come here for shopping, but I like to observe the shoppers. How persistently they keep looking for new things to acquire! I wonder why they need so many things?

Constant: That’s what keeps the economy going. Alas that they show not half as much eagerness to acquire wisdom, as you would argue. As you see, Socrates, I have remained your faithful disciple.

Socrates: You greatly honour me, my dear Constant, by crediting me with being the educator of such a distinguished man as yourself, although, as you must know, I have no knowledge of any worth myself, and so I could not have imparted knowledge or wisdom to you – or anyone else for that matter. But tell me, what are you shopping for? For I do not imagine a busy man like you walking around the mall for mere sociological observation or idle contemplation!

Constant: Well, Socrates, in a way my presence here is not free from contemplation. I am trying to see whether the mall has some old-fashioned stores among all the glitter of novelties. I’m looking for a conservative shop with conservative merchandise catering for conservative people like me. Maybe a book-store specializing in classics of literature. Perhaps a store selling proper clothes for men and for women nurtured on the tastes of older and better times. Even some solid older furniture – antique but not antiquated – might be of interest, although I don’t have much money to spend. Indeed, above all, I seek the conservative ambiance, which is disappearing from the modern agora.

Socrates: Ah, Constant, I don’t know whether you have found what you were looking for, but I have just found what will make me happy this day. I have found you, who will enlighten me as to the meaning of the word ‘conservative’, which you so persistently use. I have been puzzled by it for some time, and now that I have encountered you, who are so eager to find conservative stores and goods and even a conservative atmosphere, I am sure you will be able to explain to me what ‘conservative’ means.

Constant: You are kidding, Socrates! As always, you pretend not to know the meaning of words that are well established in human parlance, in order to test innocent but sincere people like me and examine if they know what they are talking about.

Socrates: You accuse me of a mischievous intent, my good Constant. Yet, the truth is that I have been at a loss to find a definition of conservatism, while you clearly enjoy a familiarity with the term and the philosophy underpinning it. So don’t be cruel and hide it from me, and let me share in your knowledge, so that it may benefit me, too. Or do conservatives like you wish to keep their wisdom to themselves and refuse to enlighten the ignorant?

Constant: How could you entertain such an idea? We conservatives have no intent of keeping the truth hidden in a safe. We are proud to be conservatives, and we are only too happy to spread the good tidings of conservatism to all and sundry.

Socrates: Excellent, my friend and benefactor! Tell me, then, what is a conservative?

Constant: The answer is quite simple. A conservative is a person who, like me, looks for nice old things, whether material or spiritual, and spurns all the fashionable novelties which flood our shops and our minds.

Socrates: So a conservative looks for nice old things, or nice old ideas.

Constant: Exactly.

Socrates: And if he comes across anything which is old but not nice, or an idea which is old but nasty, does he or she reject them? Or if he encounters a thing or an idea which is nice but not old, he equally repudiates them?

Constant: What is nasty or is not nice is rejected, even if it is old. What is good but not old would be acceptable after a careful examination. Yet by and large, things that have proved themselves to be nice over a significant period of time are what pass the muster of the conservative. Ideas which appear to be attractive, but which have not been established for very long, may all too often prove questionable, or even pernicious.

Socrates: Do you want to say, my friend, that the duration of an idea’s usage is a component of its value, or is that something merely accidental? Is the age of a thing or the antiquity of an idea of essential worth, just as the age of wine or the antiquity of an archeological discovery add to their respective value?

Constant: You have put it very well, Socrates. That’s exactly what I want to say. Indeed, those who disregard the test of time, and cherish things because they are new, belong to the anti-conservative camp and undermine the right way of life.

Socrates: And what shall we call these opponents of the conservatives?

Constant: I’d call them ‘progressive’, for they advocate change. They seem to expect improvement, even salvation, from a change in the current situation, even if the current situation has been established for a long, long time.

Socrates: And wouldn’t you call them ‘radical’ too?

Constant: You have taken the word out of my mouth, Socrates. Yes, they are radical, for they are eager for change and have no regard for established and well-proven practices and institutions. And you may add another label – ‘liberal.’ For they take liberties with the venerable and established, as if morality were subject to human whim.

Socrates: So it appears that the conservatives are arrayed in a battle formation against their progressive, radical, liberal enemies. The latter show little respect for tradition and established ways, while your conservatives put their trust in experience as validated by usage and history. One camp cries, “We are free to change the world! We’ll break the fetters of the past! Let’s move forward!” while the other camp shouts, “Keep things as they are, as they have been for years, for decades, for centuries. Trust the judgment of your forebears rather than follow the folly of upstarts.”

Constant: You have put it very well once again, Socrates. I am happy to welcome you into the camp of the conservatives.

Socrates portrait © Athamos Stradis 2012

Socrates: You are all too eager to jump to conclusions Constant. You remind me of a young spirited horse who is so eager to run that he does not wait for the starting signal in the race. For, my good friend, I am still very far from forming an opinion on this controversy. As a matter of fact, I still do not know what it means to be a conservative – or a liberal, a radical, or a progressive, for that matter.

Constant: What do you mean? We have just clarified the matter.

Socrates: Let me explain my difficulty. From what we have said it appears that both the conservatives and their opponents – whichever name we use for them – want what is good and right. The difference between them is that the conservatives see being old and established as a major asset for being what is right and good, while their opponents see in the novel and the changing a great chance of improvement, and thus the promise of approximation to what is right and good, even the summum bonum.

Constant: If you want to put it that way, I have no objections. Of course, though, the conservatives are right in their judgment, for they have the evidence of the past, while their opponents trust their mere dreams of the future.

Socrates: I am still far from deciding between the two camps, for I am confident that your opponents will argue that the evidence of the past cannot stand up to the ingenuity and creativity of the new generation. It is these sterling qualities , they will say, that account for human progress and hold out the promise of man’s great future. As for myself, I am at a loss and cannot make up my mind which of the two camps, if either, is right.

Constant: I can see, Socrates, that once more you are going to pretend that you know that you do not know. And once more I shall refuse to accept your claim.

Socrates: We must avoid such a discord between the two of us, good friends that we are. Let me try to explore the meaning of being a conservative from another angle. Tell me, my friend: do you attribute great weight to the old and the established in every field of human knowledge and every sphere of human conduct, or do you consider past experience as being of dominant worth in one domain and of lesser or negligible value in another?

Constant: I do not understand what you mean, Socrates.

Socrates: Let me offer you some examples. You approve of the works of art of the great artists and architects of the past, and you wish to have their masterpieces emulated by the following generations. But do you similarly endorse earlier systems of plumbing, which actually have been greatly improved in modern times? Or, to offer another example, would you have us travel by sailing ship, rather than fly, as we do nowadays, and as it was envisaged in antiquity by the radical and progressive Daedalus?

Constant: I see your point, Socrates. One should not apply the same yardstick to artistic creation and to innovations in technology. It would be foolish not to benefit from technological invention.

Socrates: And wouldn’t you give the liberal consideration you accord to technology also to the improvements in the art of medicine? Or should we rely on the old practices in caring for human health, and rule out new ideas and promising new treatments?

Constant: I’ll grant you the importance of innovation here too, if it passes the test of actually healing people.

Socrates: So you address your conservative attitude to music, poetry, religion and philosophy, while you remove those conservative restraints when dealing with technology and experimental science – whether this affects the provision of human needs, or the physical well-being of people.

Constant: We must bring under the cover of the conservative approach also the social institutions, such as family and government. These are very important domains of human experience. Some would see them as an expression of what is essentially human.

Socrates: By all means, let us include the family and the state in the realm of conservatism, and subject them to the cautious judgments of mature thinkers, learning and benefiting from the experience of many generations.

Constant: I am happy you agree with me and have embarked on the road to conservatism. Indeed, you may have arrived there already.

Socrates: Don’t rush me, my good friend. In exploring the meaning of words, I still travel by sail, and I haven’t arrived yet at a full understanding of the word ‘conservative’

Constant: What still bothers you? Let me know, and I’ll dispel the clouds of doubt which obscure the sunlight of truth.

Socrates: You are very kind. Well then, you agree that while some fields of human activity should be ruled by a fundamentally cautious, traditional, historically-minded and ancestry-revering attitude of mind, other domains need not – indeed, must not – tolerate the fetters of tradition, but ought to proceed forward daringly in their attempt to improve the human lot.

Constant: I would not put it in such an enthusiastic manner – I mean your song of praise for science and technology. Yet in essence what you say is correct.

Socrates: Alas, my friend, the division we agreed between the two spheres of human pursuits does not allay all my concerns. I still have some questions concerning those domains we have agreed to exclude from the rush and radical decisions of the curious mind.

Constant: So you plan to attack the bastion of conservatism! Go ahead; I am standing on the ramparts.

Socrates: I do not attack any bastions, and you need not watch me from the ramparts. I am merely trying, with your invaluable assistance, to find the meaning of conservatism – that is to say, if it has any consistent meaning. I have to understand what it means, before I can decide whether to accept it or not.

Constant: Ask, Socrates. Keep asking.

Socrates: Let us have a look at the institution of ‘family’. Do you agree, Constant, that family is the best setting in which to bring up children – from their birth to their maturity?

Constant: I certainly do.

Socrates: And what kind of family do you have in mind? Does it consist of a father and a mother and their children?

Constant: Of course.

Socrates: And is your approval of this family arrangement based on the experience of the past and on society’s traditional respect for family?

Constant: It’s a perfect example of the wisdom of our forebears and of the importance of following in their path.

Socrates: And what do you think of a family in which one man has two, or three, or four wives, all living together with a flock of children?

Constant: I think that would be counter to decency, to propriety, to the principle of equality of men and women. Maybe some kind of a liberal would claim such a right for himself, ignoring the rights of women. A conservative man would not indulge in such a blatant disregard of the cherished and holy tradition that regards monogamous families as the only acceptable form of this institution.

Socrates: Yet at one time in the past this was not the only kind of family.

Constant: What do you mean? It has been the only form of family in the civilized world from times immemorial.

Socrates: What about the Biblical record? Did not Abraham have a kind of second-class wife, Hagar, besides Sarah? And did not Jacob have two wives, each of whom added an additional woman in order to enlarge the family? Yet the practice is not presented as being sinful or reprehensible.

Constant: But in any case bigamy was discarded a long time ago by the civilized world.

Socrates: Precisely! When it was discarded, was this not a radical departure from a long-established practice? Whoever was responsible for introducing the exclusive practice of monogamy was not a conservative follower of tradition, but a radical innovator! Thus, it can be said that you religiously follow a radical of ancient times.

Constant: That is a strange way of putting it – you accuse me of being a radical because of my respect for a sacred institution. How can a religious conservative be a radical innovator?

Socrates: Very easily, my friend. For your Protestantism too, which you cherish and faithfully observe, was at one time a new creed which radically departed from the established belief. Indeed, Christianity separated from Judaism under the guidance of St Paul, Luther broke with the ruling Catholic church, and various sects branched off from the mainstream of Christianity in fairly recent times. Thus, every conservative Christian is at the same time a radical – even a revolutionary. A revolutionary yesterday is a conservative today. Can you see now, Constant, how the meaning of being a conservative eludes us? Can we get hold of this slippery fish, which slides out of our grip the moment we get hold of it?

Constant: I suspect, Socrates, that you have poured oil into the water to make the fish slippery.

Socrates: No, my friend, the water is crystal clear. Its clear reflection exorcizes the illusion created by a word which pretends to have a meaning and even to carry an important message. Alas, the meaning and the message remain beyond my sight.

Constant: Perhaps we can find the meaning of the word in the realm of political life. Certainly there are conservatives in politics. In Great Britain there is even a Conservative Party.

Socrates: Yes, there are people involved in politics who call themselves Conservatives, and are also called so by their opponents. And there are those who call themselves Liberals, and are described as such by the Conservatives. The problem is what these words mean – if they mean anything at all. You, my friend, consider yourself a supporter of American democracy, don’t you? And your support for it does not contradict your conservatism, does it?

Constant: Of course not! Democracy has a long tradition in this country. Indeed, the very roots of the United States are the establishment of a democratic republic.

Socrates: Undoubtedly so. But, the Republic was established by rejecting the rule of a king. Wasn’t that a radical, revolutionary move? Surely, nobody at that time would describe it as conservative! So if you put yourself in the situation of 1776, you would have to admit to being a revolutionary, ardently opposing, perhaps even fighting, the conservative establishment. Unless of course you would have chosen to remain loyal to the king and oppose the revolutionaries.

Constant: I would have done nothing of the sort. I am all for the Republic.

Socrates: So you are both a revolutionary and a conservative, an advocate of change and a preserver of things as they are. And you switch from one position to another according to circumstances. Indeed, this posture of a conservative revolutionary, or a revolutionary conservative, appears to make you – forgive me for being outspoken – an opportunist – a man without principles.

Constant: Nothing would be further from a conservative!

Socrates: Or a revolutionary, for that matter.

Constant: It seems to me that if either of us is an opportunist, the distinction should be claimed by you, Socrates, for you do not proclaim allegiance either to conservatism or to liberalism, but try to prove that each means its opposite, and that the opposite does not retain its meaning either. You confound the meaning of important principles and try to push us all into a Godless, senseless society, deprived of values and guidance.

Socrates: O my good friend, here you are quite mistaken. For I am the very opposite of what you describe. I apply my value judgments to every problem I encounter. I am what people these days call ‘judgmental’, and I do not hide it. I want to discern what is right and what is wrong, just as I want to discover what is true and what is false. Indeed, I wish to find out whether being conservative is right or wrong. So far, all I can say is that to be a conservative is right, when it is based on a right moral judgment, and it is wrong when such a moral foundation is absent, or substituted by a mistaken value. The same, however, is true of liberalism, radicalism, or whatever you choose to call the opposite. When you asserted earlier that what is nasty is to be rejected even if old, and that what is good and not old ought to be accepted, you were perfectly right. Unfortunately, you blurred the statement by loading it with a lavish praise for the old and traditional, and by a vehement rejection of innovation.

Constant: I may have overdone my point, but it was out of zeal for the conservative cause.

Socrates: Yet your zeal did not serve the cause.

Constant: No, it did not help me to convince you. It would have been effective with a less punctilious fellow.

Socrates: Yet it would not have served the cause of conservatism even then. For you do not want to recruit into your ranks men who can be won over by false arguments. You want people who become conservatives out of a true conviction – a conviction based on solid grounds and valid arguments.

Constant: Quite so. I want true conservatives.

Socrates: And a true conservative is one who cherishes the old not because it is old, and repudiates the new not because it is new, but he cherishes the old only if and when it is right, and he is ready to accept a brand new idea or conduct also if it is right.

Constant: That appears to be right.

Socrates: And can we conclude that also the liberal, radical, progressive ideas and ways have to be approved or rejected not because they have or do not have these fashionable reputations, but only in accordance with their being right or wrong, just or iniquitous?

Constant: This would be the right conclusion.

Socrates: And so we should abandon all the fancy terms and fiery slogans of both camps, bring the ardent advocates of the opposite opinions into a common site, and tell them, “Let us explore the meaning of right and wrong, and then judge our beliefs and actions accordingly.”

Constant: That would be unnecessary. For I have a good sense of what is right and what is wrong.

Socrates: Excellent, my friend. So kindly divulge your knowledge to me.

Constant: Some other time, Socrates. You may not have noticed, but, while we were discussing timeless problems, time did not stand still. I have to rush away now.

Socrates: What a pity! Just as we are coming to an agreement on an important issue, our ways part.

© Mordecai Roshwald 2014

Mordecai Roshwald is Professor Emeritus of Humanities at the University of Minnesota. He has had numerous publications, his most famous work being Level 7, a post-apocalyptic sci fi novel.