Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Existence

Barbara Smoker probes why there is something rather than nothing.

Why is there something rather than nothing?” This question is often pressed by modern Christian theologians – especially, in my experience, the Dominicans – although it was a secular mathematician, Leibniz, who first framed it, three centuries ago.

If you reply “Why not?”, the theologian will insist that if something is not self-explanatory – that is, if it exists but does not have to exist – it is natural to ask why it exists, and there should be an answer. Probably so, you counter – but that is within the system of cause and effect in which we find ourselves, and it cannot apply to the cosmos itself. After all, what the question is apparently demanding is an explanation for the whole of existence, although explanation means finding causal relationships between one event and another, and, you may counter, there is nothing known beside the universe (by the usual definition) to which to relate it.

“Not known in the experiential sense,” agrees the theologian, “but known by inference: unless the incipient universe somehow came into existence from nothing, we are forced to assume the existence of an eternal necessary being – God – independent of the universe, and in a causal relationship with it.”

This is the old cosmological argument – one of the five arguments for the existence of God advanced by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, and still the main argument underlying much God-belief (though usually less philosophically expressed). However, it does not allow for the possibility that something other than God (the cosmos itself, for instance) has always existed. Nor does it address the question, since a God would be something.

Even accepting the implied reinterpretation of the word ‘universe’ to admit something (or someone) outside it, the ‘Why’ of Leibniz’s original question and its subsequent theological answer makes no sense unless it is to question the motivation of the assumed creator – and some believers would consider that blasphemous! Atheistically, the question is unanswerable, like many of the ‘Why’ questions frequently put by small children.

Now, I agree with the theologians that something could hardly have come out of nothing, and I also tend to agree with them that it is reasonable to assume a ‘first cause’ (or, perhaps, causes) from which everything has sprung in this universe of ours – meaning this finite knowable universe, to which the opening words of Genesis (“In the beginning…”) obviously refer. But that ‘beginning’ is not, of course, necessarily the ultimate beginning of everything – if there ever was such a beginning. In any case, it is ruled out by the theological postulation of a pre-existent creator.

The anonymous author of Genesis some three-and-a-half millennia ago (traditionally Moses), would surely have been astounded to learn that this known universe has had so long a history as about 13,800,000,000 years, as has now been indisputably calculated from its expansion rate. Furthermore, if we peer backwards beyond this universe, to before the Big Bang (Fred Hoyle’s tongue-in-cheek term), we face the notion of eternity: that is, an eternal uncaused cause, rather than an entrenched beginning. Although ‘uncaused cause’ is a theological term, the concept is not necessarily theist in implication.

Modern physicists have told us that it is meaningless to say “before the Big Bang,” since that is when time itself began. Never having been convinced of this premise, my view has now been academically underwritten by Oxford Professor of Physics Roger Penrose in his Cycles of Time (2010). If this universe is merely one phase of an oscillation, as seems likely, then before the Big Bang there would have been the final collapse of the previous universe, and so ad infinitum, with a serial ‘first cause’ of each universe, totally compressed after each dissolution. The latest beginning conjecturally followed the utmost implosion of the previous universe.

Now, by what reasoning do theists give the first cause personal characteristics, calling this ‘God’? I repudiate unequivocally their unwarranted assumption that it must have been a conscious entity, with purpose and will. A simpler supposition, and far more credible, is that it was some kind of energy/matter with evolutionary potential, hardly a supernatural personage who suddenly felt a grandiose creative urge.

However, since the Lambeth Conference of 1930, only a small minority of Anglicans have denounced evolution. The Vatican quickly issued a similar capitulating decree – although both authorities insisted on the reservation that God had not only set the whole thing going, but had specially created the human mind (notably divorced from the brain). This idea was called ‘Emergent Evolution’.

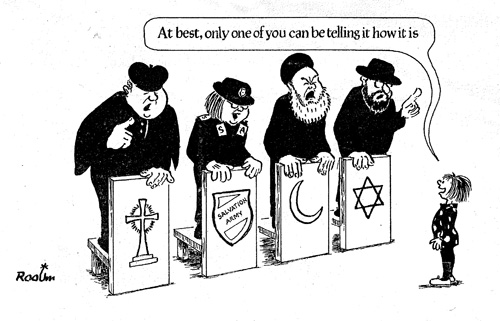

Abrahamic religions cartoon © Donald Rooum 1972

A Brief History of Atheism

In earlier times, it seemed to most people that the whole complex universe, and especially life, could only be explained by the purposeful intervention of a supernatural magician of even greater complexity. Only a few deep thinkers speculated otherwise. One of them was the materialist philosopher Democritus, who, twenty-four centuries ago in Periclean Athens, espoused the atomic theory of matter conceived by Leucippus of Miletus, and repudiated the generally prevailing belief that deliberate creation must have accounted for the universe and life.

In every age of history there have arisen other atheistic thinkers, but it has rarely been prudent for them to disclose their disbelief. To do so would often have meant risking a cruel death at the hands of believers, and it still does today in some countries where Islam has authority. In the West, this risk has now petered out, though even here it remains a common deception that atheism results in depravity.

Some 300 years ago, a French parish priest, Jean Meslier, who had lost his faith, penned a secret letter of apology to his parishioners for continuing all his life to preach orthodox Catholic untruths, so as to preserve his livelihood and, more importantly, avoid the risk of torture, imprisonment and even execution. He entrusted the manuscript to Voltaire, who accordingly published it after Meslier’s death. Just one generation later, the French atheist writer Denis Diderot edited and published the great thirty-five-volume free-thinking symposium, the Encyclopédie, which kindled the Enlightenment.

Two centuries later, in Britain, Joseph McCabe, another apostate Catholic priest, became a lifelong prolific writer against religion. I remember hearing him lecture in the 1950s, shortly before his death. A few years later I was to meet the atheist philosopher Bertrand Russell in the Committee of 100, which he had founded to deploy civil disobedience against nuclear weapons. He was then aged 90 – as I now am myself. Another decade or so on, and I shared a platform with the young Richard Dawkins, whose meteoric career was just taking off. He and the late Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, and other contemporary atheist writers on both sides of the Atlantic are now collectively dubbed ‘the New Atheists’. Although no longer in danger of being burnt at the stake, they are often under vitriolic verbal attack for speaking out against religious superstition and practice.

Meanwhile, in many of the countries where Islam rules, it is still a capital offence to come out as an atheist. There are no doubt thousands – possibly millions – of secret Islamic sceptics therefore keeping a cautious silence. We can only hope that before long they too will be free to speak their unclouded minds – as their forebears were in the later Middle Ages, when Islamic culture was far more advanced than the Christian.

Today atheism can plausibly claim to be backed by science. Physicists are in the process of discovering how, under certain physical conditions, our universe may actually have created itself. At the same time, microbiologists are on the cusp of fathoming the mechanism for the spontaneous emergence of life, through the combination of particular chemicals forming self-replicating matter. Contemporary theologians who ignore these ongoing discoveries and projections display an element of wishful thinking in their faith, at least. Moreover, the postulation of a creator fails to answer the question of ‘the beginning’, since it leaves open the next obvious question: did this creator itself have a prior creator, and so on, retrospectively forever? (Small children, on first hearing the creation story, often astutely ask, “Who made God?”) As for the question of existence itself, Bertrand Russell – though largely influenced by Leibniz – pointed out that if a creator God did exist, then he/it would ineluctably be part of existence; therefore, supposing the physical universe to be God’s creation cannot obviously explain existence itself in its entirety.

Modern Arguments

A leading exponent today of the cosmological argument for God is the American philosopher William Lane Craig. His thesis [as expounded in PN 99 – Ed] begins logically enough: “(1) Everything that begins to exist has a cause of its existence; (2) the universe began to exist; (3) therefore the universe has a cause of its existence.” But I can perceive no logic behind his then jumping to the corollary that this uncaused cause was a conscious person. I therefore agree with his cosmological argument on every point bar one: that one point being the consciousness that he ascribes to the uncaused cause.

A British promoter of these ideas is Richard Swinburne (Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, Oxford University), who has declared, “To suppose that there is a God explains why there is a physical universe at all.” He apparently sees no need to explain how this supposed deity came about, and an explanation that contains an unexplained link loses any efficacy. On the other hand, he has confidently described the Godly constitution: “God being a being to whose existence, power, knowledge, and freedom there are no limits, is the simplest kind of person there could be” (Quoted from a hand-out at a public lecture). The ‘simplest kind of person’? How, I wonder, can a being credited with omnipotence and omniscience be considered simple? Although simple life-forms can certainly increase amazingly in complexity – indeed, that is the very basis of evolution – the supposed creator who designed that potential must have been complex enough to envisage it. I raised some of these questions with Swinburne at a meeting, but his reply was too complex to be comprehensible, at least to me.

With all the true wonder that science is rapidly revealing, what need is there for jejune creationist fairy-tales? In his book for children, The Magic of Reality (2011), Richard Dawkins concludes with the words: “The truth is more magical – in the best and most exciting sense of the word – than any myth or made-up mystery or miracle. Science has its own magic: the magic of reality.” Why then, in the twenty-first century, are children still taught to believe in an unnecessary creative magician? And why is atheism still widely regarded as pernicious?

Atheism & Agnosticism

“Some forms of atheism,” declared Karl Popper in 1969, “are arrogant and ignorant and should be rejected, but agnosticism – to admit that we don’t know and to search – is all right.” Two decades earlier, having finally abandoned the Catholic faith in which I was raised (and with it, all religion), I would have agreed with him. Indeed, at that time I tended to describe my emerging philosophical position as agnostic. After all, since, by derivation from the Greek, ‘atheism’ means ‘without God’ and ‘agnosticism’ ‘without knowledge (of God)’, there is little difference in import between the two terms – so why not choose the one that has the less dogmatic tone? As time went on, however, I realised that ‘agnostic’ was usually taken to mean ‘sitting on the fence’ – which is an uncomfortable position to maintain. I had to come down on one side or the other. And since it is generally the sentiment of synonyms rather than their derivation that determines the general comprehension of one’s meaning, and I am ‘arrogant’ enough to want to make my position clear, I soon jettisoned the more nebulous label.

With regard to Popper’s insistence on continuing to search, surely enough is enough. My years of mental turmoil before managing to rid myself of childhood theistic indoctrination entailed sufficient search – through thinking, reading, listening and debating – to last me for life. We are not expected to keep a lifelong open mind on such hypotheses as the existence of Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy, so why should an exception be made in the case of God? That hypothesis, like those other stories for children, is merely asserted, without due evidence, by dissembling, or deluded, authorities.

Atheists do not necessarily reject the idea of an eternal, uncaused first cause, but regard a fundamental subatomic force as a more credible explanation than a complex, conscious, purposive creator, in a scenario that mirrors science fiction. At the same time, I admit it is impossible to be 100% certain that there was no conscious, supernatural omnipotence – that is, the theists’ idea of a God – behind the creation of the material universe and life; but we can be 100% certain that He (to use the traditional pronoun) could not possibly be simultaneously omnipotent and beneficent, as supposed in Abrahamic theology. (“Is God willing to prevent evil but not able? Then He is not omnipotent. Is He able but not willing? Then He is malevolent.”)

Philosophers often divide non-believers into strong and weak atheists – the strong being those who believe there is no God, the weak those who do not believe there is a God – the latter sort being interchangeable with the agnostics. But surely the difference is determined by the analytical definition of God, rather than the epistemological preference of the atheist. Although I am certainly a strong atheist vis-à-vis the Abrahamic religions – since the suffering in the world logically precludes belief in a creator that is both all-powerful and all-loving – I am a weak atheist with regard to any possible gods without those attributes. The label ‘agnostic’, however, is predominantly taken to mean agnostic about the existence of just such an impossible God – a God who, contrary to experience, cares about our welfare and that of other sentient creatures. And I could not go on sitting on the fence with regard to the existence of such a manifestly impossible sort of putative creator. I simply had to come down on the atheistic side and openly accept the atheist label, however traduced.

Patently, religious believers are all disbelievers in every religion other than their own. Atheists and agnostics are thus disbelievers in only one extra god and afterlife!

Now what makes believers choose the one religion in which they believe? Usually they have inherited it from their parents and previous ancestors, not thought it out on the basis of the evidence. This is proved statistically by the fact that every region of the world has its majority religion, and sometimes a second religion (often persecuted by the first). There is not an equal spread of the world’s major religions.

Mind-Blowing Cosmology

In a school text-book, Humanism, which I wrote for teenagers in 1972 (now in its Sixth Edition), I espoused the theory that the vast observable universe in which we find ourselves, comprising many billions of galaxies, each with many billions of stars with their satellites, began with a colossal explosion, the Big Bang – although, at the time of my writing it, this hypothesis was still vying for scientific acceptance with that of the Steady State model of the universe. Before long, the idea of the Steady State was dropped, since calculated predictions based on it proved to be false, while those based on the Big Bang model turned out right.

To avoid the unlikely corollary of supposing ‘something out of nothing’, I included in my book the speculative theory that our present universe might be in the expanding phase of an eternal ‘oscillation’ – it being destined after several more billion years to collapse almost to nothing (when, say, the force of the original explosion is exceeded by the gravitational pull of the mass in the universe, making it condense to an ultimate coalescence of infinite density), until the next Big Bang sets it all off again. The even more mind-blowing notion has more recently arisen that this universe of ours might actually be just one of billions of simultaneous universes having variant physical laws – known collectively as the multiverse or meta-universe or megaverse – a speculation that is given credence in Stephen Hawking’s recent book, The Grand Design (2010). The best model of this speculative multiverse is a huge conglomeration of bubble universes, each of which has its period of existence before bursting – our own universe being one such bubble. In that case, the ‘first cause’ of our universe would be the entire surrounding megacosmos.

If the physical laws of the supposed simultaneous or sequential universes did indeed happen to differ, this would enhance the possibility that at least one of them contains a galaxy containing a solar system that has at least one planet – the Earth – with the fine-tuned physical parameters necessary to bring about and maintain self-replicating matter, i.e. life; and indeed, that there are most probably many such planets. However, the observable universe, having billions of galaxies, each with billions of solar systems, is vast enough to make that virtually certain already.

Even a planet as close to us as Mars could once, it has recently been ascertained, have supported living matter, since there is evidence of the presence of water there millions of years ago. This raises a specific theological problem for Christians: if intelligent life evolved elsewhere in the universe – which is a strong possibility, given the huge number of hospitable planets there must be, with the billions of billions of worlds available – is Homo sapiens the only species anywhere that requires redemption by the self-sacrifice of God incarnate, or would that scenario need to be duplicated countless times throughout the cosmos?

Physicists working on subatomic particles in the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva claim they have detected ‘the god particle’ – more technically called the Higgs boson, named for Peter Higgs. In 1964, he theorised its coming into existence within a nano-second of the Big Bang to explain why particles have mass, and so why matter operates under the influence of gravitational force. But this creative force is hardly recognisable as the theists’ father-figure superman.

The theistic scenario seems to be that the supreme being, after an eternity of non-creation, decided suddenly to actualise a universe – a universe which, although designed for enormous expansion, was supposedly created merely for the sake of one tiny planet in a small solar system of a particular galaxy, as the specific habitation for a congenial Man Friday life form. It is the arrogantly anthropocentric belief shared by many millions of god-believers: that the whole complexity of the universe, of space and time, was specially devised by their god(s) with the sole motive of producing human beings on Earth as ‘objects of his love’. I relish Voltaire’s mockery of this idea, in which a house-fly, finding itself in the Palace of Versailles, looks around in amazement at the size and splendour of the structure and its decor, and thinks to itself: “Fancy, all this has been created just for me!”

Atheist Conclusions

Anyway, what sort of love is it that the putative creator is supposed to have for his creatures? Not only is evolution based on the principle of the weakest going to the wall, but all the suffering endured by earthlings, including ourselves – whether caused by parasites, predators, diseases and natural disasters, or by human inhumanity – can only mean that this purposive God, all-knowing and omnipotent, lacks any sense of moral purpose as we conceive it, and cannot possibly empathise with our situation. This inevitably raises a philosophical problem, but only for those who cling to the belief that the first cause was a conscious being and insist that he (?) is a caring creator. We non-believers have no such philosophical problem, since we posit no wilful intention behind all the widespread suffering, which we see as random, not deliberate. For us, the only problem that arises is how to meliorate this suffering.

Despite (or perhaps because of) this manifest lack of morality in life’s conditions, most human beings, and many other animals, show altruism, at least from time to time. Perversely, this is seen by theologians as a reflection of perfect divine goodness – thus providing them with another argument for the existence of God. But the rational explanation for altruism is its species survival value, facilitating its emergence through evolution by natural selection.

To return finally to the question of existence, there are only two possibilities – something existing, or nothing existing – and the evident fact is that things do exist. Since it is impossible, by definition, to encounter anything behind the totality of existence, existence itself cannot have a cause. The question why there is something rather than nothing is therefore unanswerable. While observable things can be described and explained piecemeal, and science is rapidly expanding our explanation of them, a hypothesis of some basic eternal potential is as far as we can speculate, there never having been a true beginning. Although, within the universe, time is inseparable from space, I envisage time as existing without space before the Big Bang.

While we are bombarded with supernatural explanations galore for existence, they invariably posit an antecedent creator, thus begging the question. So no longer can God (or gods) provide a rational solution to an exigent riddle. Hence, atheism is now coming into its own – although the New Atheists are ‘new’ only by virtue of the newness of extensive electronic communication.

© Barbara Smoker 2014

Barbara Smoker, one of Britain’s best-known atheist authors and speakers, was President of the National Secular Society from 1970-95.