Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

Alistair MacFarlane appreciates the life of an infamous art prophet.

Before Marcel Duchamp, a work of art was an artefact, a physical object. After Duchamp it was an idea, a concept. Duchamp did to art what Einstein did to physics and Darwin to religion: each destroyed the foundations of a subject – although they did so in very different ways. Einstein thought long and hard until he formulated his new vision of the physical world. Darwin agonised for decades, making himself physically ill, before announcing that we were merely members of the animal kingdom. In stark contrast, Duchamp approached the demolition of the art establishment and the pretentiousness of artists with the cold-eyed calculation of a saboteur looking for the best target. He found his target in New York in 1917.

Early life

Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville-Crevon in the Seine-Maritime province of upper Normandy on 28th July 1887. His mother Lucie (née Nicolle) was the daughter of a painter and engraver, and his father Eugene a local notary. The art of his maternal grandfather filled their house, and the young Marcel and his three surviving siblings absorbed artistic sensibilities from infancy. All four children took up art. Marcel became a painter; one elder brother Jacques a painter and printmaker; his other older brother Raymond became a very distinguished sculptor; and their young sister Suzanne another painter.

After winning a prestigious prize for drawing at school, Marcel decided to follow his elder brothers and study at the Académie Julian. Helped by the patronage of Jacques, who had become a member of the Académie Royale, he exhibited in the 1908 Salon d’Automne, becoming a lifelong friend of the artist Francis Picabia and the critic Guillaume Apollinaire. Duchamp’s brief career as a pure painter culminated with his masterpiece Nude Descending a Staircase (now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art), which was submitted to the Cubist Salon des Indépendents in 1912. The organisers of that exhibition asked his elder brothers to persuade him to withdraw the painting or to paint over its title. He promptly went to the showroom in a taxi and removed it from the exhibition. This was a turning point in his life, which he thereafter largely devoted to seeking an answer to two questions: What is to be deemed acceptable as art? and Who decides?

After gaining exemption from military service, Duchamp felt increasingly uncomfortable in France, and in 1915 decided to emigrate to the United States. Several of his paintings had been purchased there, so he could afford to move. On arriving he found he was a celebrity there, and he made it his home, eventually taking citizenship in 1955.

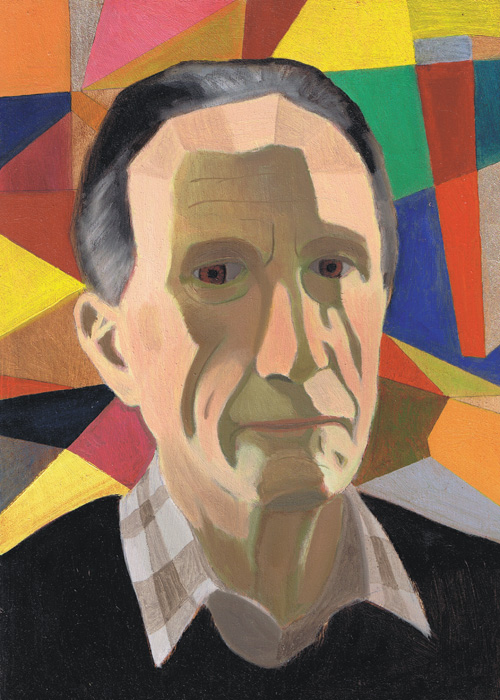

Portrait of Marcel Duchamp © Darren McAndrew 2015

Fountain

Duchamp had two strategic objectives. First, to destroy the hegemony exerted by an establishment which claimed the right to decide what was, and what was not, to be deemed a work of art. Second, to puncture the pretentious claims of those who called themselves artists and in doing so assumed that they possessed extraordinary skills and unique gifts of discrimination and taste. Tactically he sought to make a very bold, and very public, gesture, by seeking to submit some totally outrageous entry under conditions the art establishment would be forced either to accept under their own rules, or to break these rules, giving reasons for rejection. He saw the perfect opportunity in an exhibition planned by the Society of Independent Artists in New York in April 1917. He was a member of the committee, whose rules explicitly stated that all works submitted would be exhibited. This aimed to be the biggest event of its kind, having 2,500 works submitted by1,500 artists, and so would attract the kind of attention Duchamp sought.

On 17 April, 1917 he discovered an ideal exhibit when strolling along Fifth Avenue in the company of Walter Arensberg, his patron, a collector, and Joseph Stella, a fellow artist. When they passed the retail outlet of J.L. Mott (now alas no longer there), Duchamp was fascinated by a display of sanitary ware. He had found what he had been diligently seeking; and persuaded Arensberg to purchase a standard, flat-backed white porcelain urinal. Taking it to his studio, he placed it on its back, signed it with the pseudonym ‘R.Mutt’, and gave it the name Fountain. It is the only submission to the exhibition which is now remembered, since after having been on display for a short while, the organising committee, suitably outraged, rejected it.

However, his shrewd two-way bet had succeeded beyond Duchamp’s wildest expectations, and he achieved the notoriety he was after, and subsequently seismically shifted the thinking of the art world. In 2004, a panel of artists and art historians voted Fountain as the most influential artwork of the Twentieth Century. Duchamp’s place in the history of Art was commemorated in 2000 by the founding of the Prix Marcel Duchamp – an annual award given to young artists by the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. That a tribute to his work should be associated with a building which its architect turned inside out would have greatly appealed to Duchamp.

The original Fountain has disappeared, although a photograph exists, and seventeen copies exist in various art galleries.

The Philosophical Aftermath

Over the centuries, hundreds of artists have produced thousands of accepted masterpieces which adorn museums and galleries worldwide. Until the early Twentieth Century it had seemed fairly clear what these works had in common: they were all physical artefacts such as paintings, sculptures, engravings, and etchings, which showed exemplary craftsmanship and were representations considered beautiful, interesting or inspiring. Today it seems that anything goes in art galleries: animal carcasses; unmade beds; comic book paintings; huge statues of Disney characters; rows of bricks; live performances; created landscapes – whatever. It would be totally unreasonable to claim that such a dramatic change could be laid at the feet of one man. It would equally unreasonable to ignore the impact made by Duchamp. It also seems ill-advised to claim, as the philosopher Arthur Danto once did, that this change means that art is now dead. On the contrary, art seems to be flourishing as never before.

What has happened is that there has been a progressive demolition of practically all the conditions which had been regarded as mandatory for something to be considered a work of art. Art no longer has to represent anything, nor even to be beautiful (although of course it can be), nor require exemplary skill for its production (although that might be so, too). Neither does it have to be made by the putative artist, who can simply put forward an idea for somebody else to make or perform. Why one should then be regarded as an artist, and the other not, is an interesting philosophical question in itself. Another question – very pressing if you’ve just spent a fortune on a Picasso – is, if it were possible to make exact physical copies (as soon may be the case using high-fidelity 3D printing), why should only the original be a work of art?

It cannot be the case that absolutely anything can be a work of art, since then everything would be a work of art. The real problem – and this is Duchamp’s great legacy to philosophy – is that we now need to work out a sufficient set of conditions for art. Several philosophers rose and are rising to this challenge. Nelson Goodman sought to treat all manifestations of art – painting, sculpture, music, literature, performance and dance – in terms of a general theory of symbols – thus examining the languages of art. As mentioned, Arthur Danto set out to establish that art was dead; then changed his mind, explaining why this in fact is not the case. What does certainly seem to be dead are old fashioned philosophies of aesthetics.

Although an accomplished and versatile artist, Duchamp’s contribution to philosophy has proved greater than his contribution to art. Art requires our left brains and our right brains to talk to each other, and so give meaning to experiences which lie beyond the grasp of reason. Exactly how this works and what its limits are (if any) poses philosophical problems of great relevance, importance and difficulty, whose solutions would bring a greater breadth and balance to our cultural life.

Last Words

During the 1920s and 30s, Duchamp became a chess master and an authority on the game. For the rest of his life this passion excluded most other activities. When his wife left him, finally unable to cope with his obsessive personality, she made an appropriately powerful gesture, glueing his favourite pieces to his favourite board. Duchamp must have felt that at least this showed a sound grasp of one sufficient condition for the production of a work of art: she had made a telling statement without using words.

Marcel Duchamp died on 2nd October 1968 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, and was buried in Rouen Cemetery. On his tombstone he had arranged for an engraving: “D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (“Anyway, it’s always the others who die”). In so doing he had, most fittingly, made his memorial both a philosophical statement and a work of art.

© Sir Alistair MacFarlane 2015

Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor.