Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Philosophical Haiku

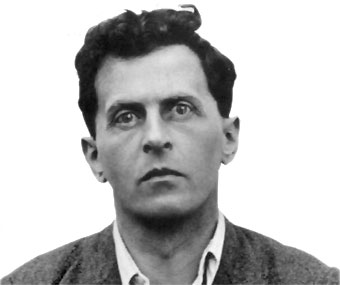

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

by Terence Green

World as facts, not things

Understand without knowing.

On the other hand…

It takes a brave man to declare that his ground-breaking work that people had hailed as a revolution in philosophy was muddle-headed, but that’s exactly what Wittgenstein did.

Born into a fabulously wealthy family in Vienna, as a young man he went to Britain, where at first he studied engineering at Manchester. At this time he noticed some intractable problems in the foundations of mathematics, so he decided to make them more tractable. After visiting Gottlob Frege in Jena, he nipped to Cambridge to see what Bertrand Russell thought. Russell thought he was crazy, but also a genius. Then WWI intervened, and so Wittgenstein headed back home, to end up fighting the Brits. Luckily for him, he was taken prisoner: he used this leisure time to write his first masterpiece, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which described how he then thought language and logic worked. For one thing, he said, the world is not made up of things, it is made up of facts — what are called states of affairs, or the way things relate to each other. In short, after several thousand years of fruitless endeavour on the part of all his hapless predecessors, Wittgenstein claimed that he had solved all philosophical problems. And so, with nothing more to be done in philosophy, he went off and became a school-teacher for six years in the wee Austrian village of Puchberg am Schneeberg (imagine his homework assignments!).

Then he began to have second thoughts: maybe he hadn’t solved all of philosophy’s problems! So he decided to go back to Cambridge. But first he had to overcome a very unphilosophical problem — he had no money. Having inherited a vast amount, he’d given it all away because he thought it would hinder his thinking (I find it works the other way, myself). A collection was taken for him, and he got back to work. Not published until after his death, his Philosophical Investigations challenged his earlier work to its very foundations.

Wittgenstein taught that in the end philosophy seeks not knowledge, but understanding. Whether they understood him or not, later philosophers were happy Wittgenstein hadn’t solved all of philosophy’s problems. They’d all be unemployed if he had.

© Terence Green 2017

Terence is a peripatetic (though not Peripatetic) writer, historian and lecturer. He holds a PhD in the history of political thought from Columbia University, NYC, and lives with his wife and their dog in Wellington, NZ. He blogs at hardlysurprised.blogspot.co.nz.