Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Pugnacious In The Punjab

Seán Moran considers holy war in Lahore.

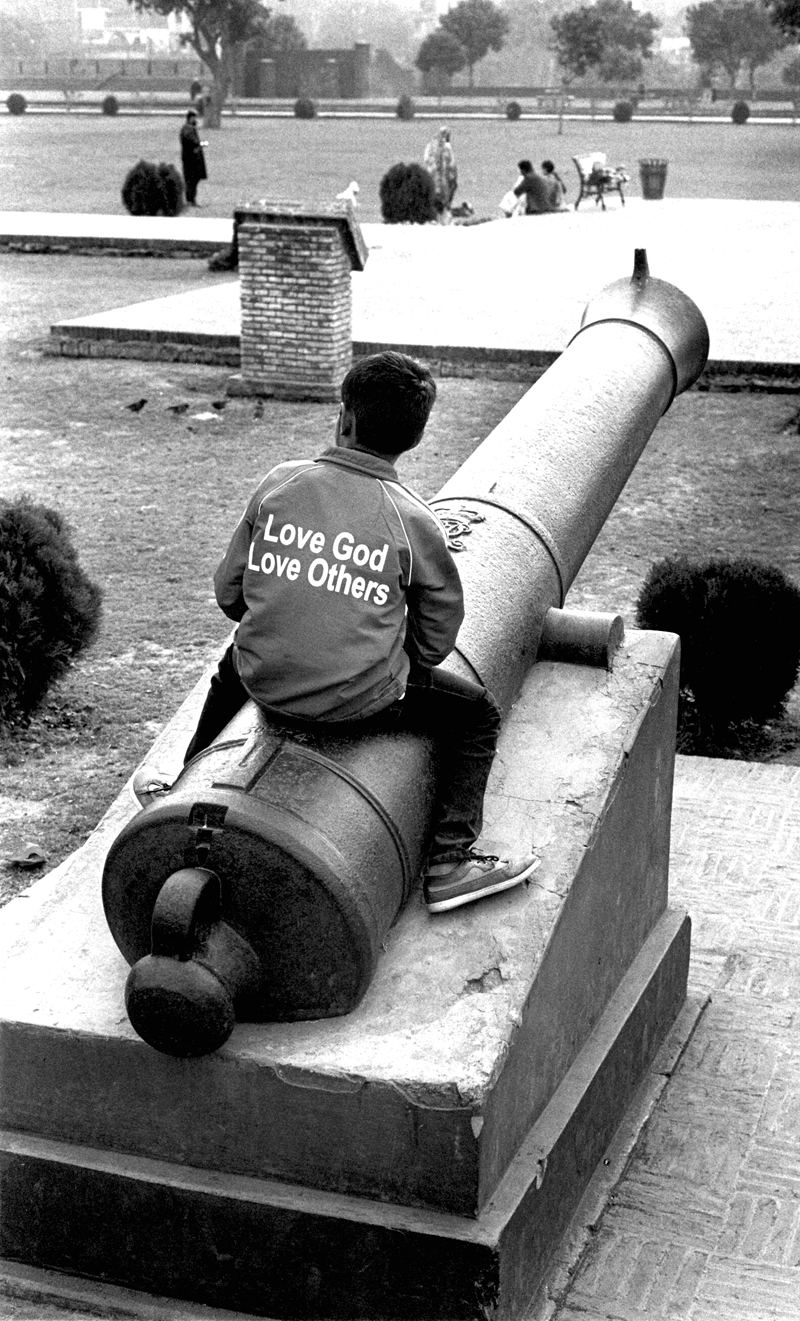

My photograph is genuine. The words on the boy’s back are real, and the cannon, outside a fort in Pakistan, is authentic. It dates from the Eighteenth Century and is embossed with the symbol ‘G3R’: ‘King George III’. He’s the mad king whose behaviour eventually led to the second amendment of the American Constitution – the right to bear arms – in case his troops should reappear with cannons and muskets. (I oversimplify a little here.) What drew me to the scene was the incongruity of a peaceful religious motto next to a weapon of war.

Pakistan has certainly had its share of violence, and we hear much about Islamist aggression in the world at large, which the belligerents excuse by talk of historical injustices. Some people polarise the world into ‘Crusaders’ and ‘Jihadists’; but we can make few valid generalisations about 2.3 billion Christians or 1.8 billion Muslims. It claims too much if a small number of outliers are allowed to define the whole category. Unfortunately, many non-Muslims flinch when they hear the phrase “Allahu Akbar!” – “God is the greatest!” – because on the television news the shouted slogan is typically followed by a bang.

Religion has been behind certain conflicts. But it can also be a useful cover story to justify the unjustifiable, with no genuine link to faith. The troubles in Northern Ireland – now largely resolved, happily – were not a theological dispute. Religion can be like patriotism: the last refuge of a scoundrel. Yet some of the finest people have faith too. And a number of the most genocidal leaders in history felt no need to invoke God as an excuse for their crimes against humanity. Stalin in the Soviet Union, Mao in China, and Pol Pot in Cambodia, were all atheists; and self-worshipping Kim Jong-Un waits in the wings in North Korea.

We might reasonably expect religion to engender peace, not conflict, since just about every religious doctrine favours treating people how you would like to be treated (secular humanist principles embody this ‘Golden Rule’ too). Some codes go even further, by demanding that we treat our enemies well: “Whoever pardons [an evil act] and makes reconciliation – his reward is due from Allah” (Qur’an 42:40), or “Love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you” (Matthew 5:44). And no-one should force their theological views on others at the muzzle of a gun: “There is no compulsion in religion” (Qur’an 2:256).

So how is it that aggressors commit atrocities with religious motivations? One standard answer is that they are not truly members of the religion in question. After an Islamist outrage, for example, moderates say: “No true Muslim would do such an appalling thing. Islam is a religion of peace.” In Northern Ireland, terrorists on both sides were deemed to be ‘not real Christians’ by others who claimed to be real Christians. Disputing this, militant atheists point to aggressive verses in both the Qur’an and the Bible. They are ‘real’ Muslims or Christians, they claim: the attackers are being true to their holy books.

This argument is unconvincing. For while the Qur’an has some ‘sword verses’, and the Old Testament has a certain amount of smiting, the overall tenor of both written codes is one of peace, harmony, and reconciliation. Does that mean, then, that we can legitimately assert that ‘no true X’ (where X is Christian, Muslim, etc) would commit violent acts? I would say no, since claiming that the aggressors are ‘not really X’ is an example of the logical fallacy called the ‘appeal to purity’. We are illicitly re-drawing the Venn diagram of who’s in and who’s out to exclude those cases that don’t suit our argument. And while a perfectly good Christian or Muslim would never do any wrong things, such individuals are rare. Every church and mosque would be empty if perfection was an entry requirement. Religion is more help to sinners than saints. Indeed, our Venn diagram can be manipulated to exclude everyone who fails any arbitrary criterion that we choose. The late English philosopher Antony Flew called this faulty logic the ‘No True Scotsman Fallacy’, since his illustration relied on the traditional Scottish seasoning for porridge being salt. A conversation between Adam and Bob about the breakfast habits of Scotsmen might go like this:

Adam: “No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge.”

Bob: “My Uncle Angus puts sugar on his porridge, and he’s a Scotsman.”

Adam: “In that case he’s not really Scots: no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge.”

Adam has tried to make his assertion unfalsifiable. Bob’s reasonable counterexample about Uncle Angus is swept to one side, and Adam insists on his own purist criterion. In reality, some Scotsmen and Scotswomen do put sugar on their porridge; and some Muslims – together with Christians, atheists and so on – do commit atrocities. But it is not an essential requirement of ‘Scottishness’ to eat sweet porridge, nor a central part of ‘Muslimness’ to be bloodthirsty, either.

In fact, during several visits to Pakistan I have never encountered any belligerence (nor porridge-fuelled rage in Scotland). I’ve only ever experienced friendliness and hospitality, although I’m visibly a Westerner. Admittedly, I was once a little worried by an eccentric local chap I bumped into on the streets of Lahore. He insisted on giving me a guided tour of the Jinnah library. While we were having tea and cakes in the library café afterwards, he revealed that the Pakistani secret services had tried to recruit him as a body double for the then President of Pakistan, General Musharraf (he did look remarkably like him). Cakes finished, we stepped outside into the warm evening air so that he could have a smoke. Someone appeared out of the shadows and lit his cigarette for him. The Presidential lookalike then asked me if I wanted to join him on his jihad. It was an awkward moment. But his jihad turned out to be his personal mission of warning people about the harmful effects of skin-lightening creams. It was good to see such a heavy smoker concerned for public health.

Photo © Seán Moran 2017

I breathed a sigh of relief once it was clear that he used the word ‘jihad’ in the sense of ‘striving towards a praiseworthy goal’ (the greater jihad), rather than ‘holy war’ (the lesser jihad). But there are fanatics who do go by the latter definition – or rather, by their own version of it. They have a misguided sense of tidiness, in wanting everyone’s belief-sets to be congruent with their own. Such Jihadists are so concerned about the allegedly mistaken viewpoints of others that they try to erase those opinions, together with their holders. So in its own twisted way, violent extremism is an appeal to purity, too. Except the theological equivalent of putting sugar on your porridge can get you killed. The Irish Eighteenth Century thinker Edmund Burke evaluated this revolutionary mindset pithily: “By hating vices too much, they have come to love men too little” (Reflections on the French Revolution, 1790). But it is hard to disentangle how much of the violence is really linked to a concern for virtue, rather than to high testosterone, low self-esteem, frustration, and a toxic combination of circumstances.

Those suffering attacks on their values are in a difficult position. Turning the other cheek may be a suitably pacifist reaction to a face slap, but the slaughter of innocents is a different matter. Philosophers can help to calibrate an ethical response, and perhaps show the folly of some populist sabre-rattlers (such as the minor UK politician who recently demanded the reinstatement of the death penalty… for suicide bombers).

One written ethical defence against religiously-motivated aggression is: “Those who have been attacked are permitted to take up arms because they have been wronged.” The list includes “those who have been driven unjustly from their homes only for saying, ‘Our Lord is God.’” Otherwise: “many monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques, where God’s name is much invoked, would have been destroyed.” Perhaps surprisingly to some, this precept is from the Qur’an (22:40). It gives permission for reasonable self-defence, to Jews and Christians as well as Muslims. An extension of this is the ‘just war principle’ of international law, which the medieval philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas (among others) helped develop, in his Summa Theologica (1274). This does not allow anybody to take up arms and join battle for the sake of just any perceived wrongs, but sets out certain conditions for war to be ethically justifiable. Aquinas’s first requirement is that of auctoritas principis: having the legitimate authority of your country’s leader: not so straightforward if the commander-in-chief is mad (naturally, I am referring to George III here). Second, there must be a causa iusta: a just cause. Third, is the need for intentio bellantium recta: that the belligerents “intend the advancement of good, or the avoidance of evil.”

These principles form the core of Western thinking about the ethics of going to war. But they also appear in the rules of jihad (with certain modifications, such as the Caliph – the religious leader – being the legitimate authority, and “the advancement of good” taking on a more explicitly religious tone). In the Seventh Century CE, the first Caliph, Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, formulated ten rules for battlefield conduct. These protected women, children, the elderly and monks from harm, and forbade the destruction of inhabited areas.

When judged against the criteria of Aquinas, al-Siddiq and others, it’s clear that much religious violence is neither ‘just war’, nor jihad, nor even religious in origin. If the belligerents would only sit and read the key writings on these matters, they might have second thoughts. Unfortunately, the quiet reading of philosophical and theological texts is probably not as exciting as causing mayhem.

Although the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has its troubles, it was heartening to see the boy dismount the cannon and stroll around his home town of Lahore, together with his father, mother, brother and sister. They were all confidently dressed in identical jackets bearing the same peaceful slogan.

© Dr Seán Moran 2017

Seán Moran is in Waterford Institute of Technology, and is a founder of Pandisciplinary.Net, a global network of people, projects, and events.