Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

To Be Born: Genesis of a New Human Being by Luce Irigaray

Dharmender Dhillon muses on Luce Irigaray’s best way to make an individual.

Luce Irigaray is a highly influential French cultural theorist, philosopher, and psychoanalyst. Her latest offering, To Be Born: Genesis of a New Human Being (2017), is a dense but readable defence of individuality amidst a culture that fosters conformity.

Irigaray’s ‘continental’ approach – that is, seeing philosophy as a way of life irreducible to mere formal study – is evident from the outset, in a cryptic prologue. Thankfully, once we get past the initial jargon-laden introduction, the main body reads well, and her conclusion follows from the premises she’s outlined. The writing is emblematic of Irigaray’s trademark, highly creative, ‘Hegelian-Nietzschean phenomenology’. In other words, she interrogates concepts from the point of view of human experience with an equal amount of scepticism and fascination.

Irigaray (photo by Babette Babich)

In sum, Irigaray argues for individual creativity. The central strand of the argument portrays the nurture and socialisation of a child within contemporary Western culture as limiting their potential. She advocates solitude and a space for individuation amidst an oppressive social totality. As such, echoes of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), as well as the Critical Theory of Theodor Adorno (1903-69) and the ideas of Michel Foucault (1926-84), are all apparent. The latter two thinkers both investigated ways in which Western society seeks to mould and control subjects, especially through culture and education. The term ‘subject’, popularised by cultural theorist Stuart Hall, is itself telling; for under modern social norms, an unimpeded individuation cannot occur. Rather, the individual is subject to a myriad of forces seeking to control him or her: “When it is presumed that [a child] has reached being a human… it has become a made product instead of developing” in its own unique way (p.16). Irigaray desires that we “venture beyond what is already experience[d] of life” (p.7). She thinks in these terms because she, like Nietzsche before her, is interested in shaking up what she deems a decadent prevalent discourse in which “one wastes away because of ennui, disgust, melancholy and weariness” (p.27).

Echoing Nietzsche, Irigaray argues that humanity as it is ought to be overcome, and that existing customs are ill-equipped to facilitate this. In response to this challenge, Irigaray turns to traditions from the East, such as yoga, as a means of nurturing individuality through inwardness: “a cultivation of breathing allows us to assume the solitude of our singularity” (p.x). She acknowledges that the challenging of norms is not without danger, but that by centring oneself through the cultivation of breathing exercises, for example, individuals may develop the courage and attentiveness to transcend dominant societal norms.

Nietzsche’s Shadow

Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-1885) casts a large shadow over To Be Born: it is the only work of his cited in the bibliography, and the source of the closing line of the text. What is slightly problematic or uncharitable, depending on how one chooses to read it, is how Irigaray’s text is essentially an exposition of Nietzsche’s ‘three metamorphoses of the spirit’ as outlined in Zarathustra, without ever once explicitly acknowledging them.

In the ‘three metamorphoses’, Nietzsche dictates how one is to transfigure oneself from a burden-carrying ‘camel spirit’, who understands the morality in which one resides but does not wish to partake in it; to the freedom-seeking ‘lion spirit’, who, liberating itself from the burdens of the camel, seeks to assert its moral agency; to the liberated ‘child spirit’, who is able to create new values. Nietzsche elaborates this through his description of the child spirit as representing “innocence and forgetfulness, a new beginning, a sport, a self-propelling wheel, a first motion, a sacred Yes… the spirit now wills its own will, the spirit sundered from the world now wins its own world” (Thus Spake Zarathustra, trans. R. J. Hollingdale, p.55).

Building upon this notion of ‘willing its own will’, Irigaray argues that a child ought not be forced to adapt itself to the world, but instead “transform this world according to its potential and its desire” (To Be Born, p.28). This is clearly a highly utopian and indeed speculative claim, for it cannot prescribe what such transformation would consist in. It is also debatable whether the exercising of such a will would necessarily engender socially beneficial outcomes.

Also following Nietzsche, Irigaray’s championing of individual creativity amidst, and against, socially sanctioned but repressive norms deems that any such response will necessarily be maligned owing to its very eccentricity. As she notes: “important aspiration or creativity is not tolerated” (p.59).

Language & Control

Irigaray, like many of her predecessors in the Continental tradition (not least of all Nietzsche), believes that language, as opposed to giving individuals the tools to fully express themselves, has come to limit their potentials. That is to say, we currently fail to use language in a way that might help individuals fulfill their potential: “At school, in our culture, the child thus learns what is, or would be, the world, but not what or who it, itself is. For teaching it what the world is, teachers first instruct it in using language. It is taught how to speak, to read, to write, as one handles a tool, a machine, not to say a weapon, which it will interpose between the world and itself. Its linguistic performance will amount to dominating the world” (p.57). Pulling the proverbial rug from beneath herself – using language to critique language – is but another part of Irigaray’s project of shaking up norms.

Irigaray claims that every child is capable of a ‘natural growth’ according to their own particular potential. However, this growth is corrupted by those upon whom every child initially depends because the culture into which we initiate children does not facilitate their natural, individual flourishing. In an observation that could have been lifted from the scathing cultural critique of Dialectic of Enlightenment by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer (1944), Irigaray asserts that “various techniques, by substituting themselves for the motion of a natural growth, will paralyze and distort [such growth], and transform human being into a sort of automaton in which a part [the care-giver], determined by culture, exerts control over another part [the child], which remains faithful to nature, in order to master it while exploiting its energy” (p.15).

Conspicuous by his absence in To Be Born, Adorno has much to offer when addressing the problem of humanity’s linguistic specification and domination of nature. Concerned with combating the idea that language and science allow for exact knowledge of, and so control over, the natural world, it is through Adorno’s concept (or rather, non-concept) of ‘non-identity thinking’ that there lies hope for Irigaray’s utopian aspiration for individual creation outside of cultural domination. Non-identity thinking involves playing concepts off against each other to reveal their inconsistency. In doing so, the totality is revealed as false, and there remains a minutia of hope for new forms of communication and creation that are not simply the instruments of existing social norms. Non-identical communication meets Irigaray’s utopian aspiration that “Henceforth, the matter is no longer one of recognizing what or who appears to us according to the discourse that we have heard about it or them, but of preserving a space for the not-said, not-defined, not-determined, in which this other can appear as something or someone that is not yet known or recognized” (p.66).

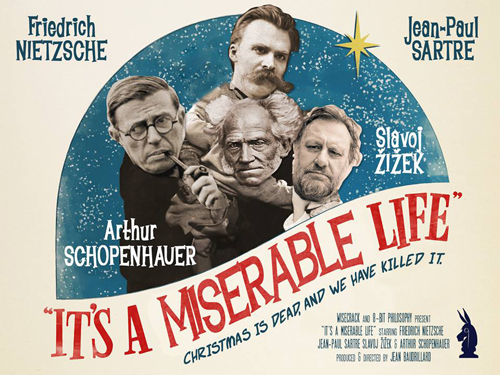

I don’t know who did this, but cool poster, get in touch.

Shock The Monkeys

Explicitly and implicitly combining these Nietzschean and Adornian lines of thought, Irigaray proposes that it is through solitude and non-dominant communication that individuals can engage in discourse that’s different from that of the prevailing logic.

The prevailing neoliberal logic of individuation only serves the dominant discourse, which is based on capitalist competition and the threat of scarcity. Against this, Irigaray harnesses and rekindles Nietzsche’s diagnoses of his century’s fin-de-siecle malaise to argue that “our religious, cultural and political ideals are unable either to secure the safety of humanity or to offer a plan for constructing a future which corresponds to our current necessities” (p.99). Not shy of exercising her own eccentric creativity, Irigaray responds to critics by asserting that those who laugh at her utopian proposals contribute “only towards wasting the remainder of our living energy for the automation of a world in which people turn into robots – which amounts to the fabrication of monkey-like beings” (p.103). Observing much present-day party politics and the schooling of governing elites, it’s arguable that Irigaray’s diagnosis is unfortunately all too insightful.

© Dharmender S. Dhillon 2018

Dharmender S. Dhillon still sees Herr Nietzsche in, well, everything: it’s getting mighty tiring!

• To Be Born: Genesis of a New Human Being, by Luce Irigaray, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, 120 pages, £17.99 pb, ISBN: 3319392212