Your complimentary articles

You’ve read two of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Beauty versus Evil

Stuart Greenstreet asks whether we may judge a work to be artistically good even if we know it to be morally evil.

“It is not an accident that the artistic manifestations of Fascism were banal in the extreme,” John Casey writes in The Language of Criticism (p.54, 1966). It is not an accident, the argument goes, because works of art take their character from their makers. Art draws on what is distinctive about how artists view the world and the attitude that they take towards it. So Fascist art, for instance, is bound to be bad because it instantiates Fascist values and a Fascist worldview. This amounts to claiming that it is impossible for evil individuals and institutions to produce laudable art, or for a work of art to be artistically good if it is also morally bad.

This claim is severely tested by Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 film Triumph of the Will, a piece of Nazi propaganda which Hitler commissioned and helped to produce. It is not banal. It is commonly judged to be both beautiful and evil; the artistic and moral criteria tug in opposite directions. The basic evaluative question, therefore, is whether the film’s evil content nullifies its artistic merit.

Triumph of the Will is a film of the 1934 Nuremberg party rally, one of several giant rallies promoted by the Nazi Party in the 1930s. The rally lasted seven days, involved thousands of participants, and was estimated to have drawn half a million spectators. Hitler went to Nuremberg to help to organise the spectacle that involved thousands of troops, marching bands, and ordinary citizens. The film was made at Hitler’s request and with his support; he even gave it its title.

As a work of propaganda, designed to spread the Nazi creed and mobilize the German people, Triumph of the Will presents National Socialism as a political religion. Its images, doctrine, and narrative all aim at entrenching its tenets: Ein Volk. Ein Führer. Ein Reich. Germany is one nation, Hitler is an inspired leader, and the Third Reich will last a thousand years. The film’s most unsettling feature is how it presents a beautiful vision of Hitler and the New Germany that is morally evil. Here is one critic’s reaction:

“Triumph of the Will is a work of creative imagination, stylistically and formally innovative, its every detail contributes to its central vision and overall effect. The film is also very, very beautiful. … Its every detail is designed to advance a vision that, as history was to prove, falsified the true character of Hitler and National Socialism. … [The film] renders something that is evil, namely National Socialism, beautiful and, in so doing, tempts us to find attractive what is morally repugnant.” [From Mary Devereaux’s essay ‘Beauty and evil: the case of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will’, 1998. I have drawn on parts of her essay in writing this article.]

There is a standard solution for tackling the problem of evaluation that arises when beauty is entwined with evil in a single work of art. The solution is known as ‘formalism’: it puts an iron curtain between the ‘form’ of an artwork and its ‘content’. ‘Form’ is shorthand for a work’s ‘formal features’, which in visual art (including film) include balance, symmetry and perspective, all of which are usually achieved by the arrangement of shapes and lines and colours. In music formal features can include the key chosen, the rhythms, the role of different instruments, and the intervals between notes.

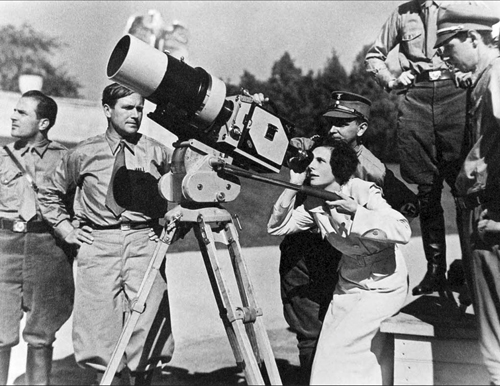

Leni Riefenstahl and her camera crew filming Triumph of the Will in 1934.

We take in the formal features through our eyes (in all visual art); or though our ears (in music); or through eyes and ears, in ballet, and in drama performed on either stage or screen. Whereas an artwork’s formal features engage our senses, its ‘content’ appeals to our mind and our emotions. It makes us think and feel. So ‘content’ refers to the meaning or message ‘contained’ in works of art, which their makers strive to express.

Formalism asks us to evaluate art narrowly, solely in terms of its formal features; and to keep that assessment apart from any parallel evaluation of its emotional, political or other content. But is this actually possible? Consider these two critical descriptions of a musical work, first in terms of its formal features:

The work opens in C major but then changes to a minor key; the theme introduced by the oboe is taken up by the violins; the rhythms become increasingly syncopated…

Now in terms of the emotions expressed (the work’s ‘content’):

After a serene and joyful opening the music becomes progressively more disturbed and anguished until at last it issues in a final outburst of grief.

Try to imagine a critical description of Beethoven’s 9th symphony (The Choral) that ignored its content and referred solely to its formal features. By failing to mention the symphony’s optimism and nobility the critic would defraud us. But suppose that we could make a purely aesthetic evaluation of a work’s formal properties without discussing its content. That would let us ignore the Nazi propaganda in Triumph of the Will and judge it (as ‘art for art’s sake’) purely in terms of it formal qualities. In that case we would be free to judge it artistically good even if we know that it is morally bad. However, as we shall see, this isn’t a practical solution, let alone a morally acceptable one.

In the best works of art form is fused with the content. Consequently the value of such a work (as art) is not something that can be judged apart from the moral qualities of its content. This is what F.R. Leavis meant when he said “works of art enact their moral valuations.” When we examine the formal perfection of Jane Austen’s novel, Emma,

“we find that it can be appreciated only in terms of the moral preoccupations that characterise the novelist’s peculiar interest in life. Those who suppose it to be an ‘aesthetic matter’, a beauty of ‘composition’ that is combined, miraculously, with ‘truth to life’, can give no adequate reason for the view that Emma is a great novel and no intelligent account of its perfection of form.” [F.R. Leavis, The Great Tradition, p.8, 1960.]

Form and content are not two discrete elements which Austen miraculously combined: it is the novel’s aesthetic form which in itself ‘enacts’ (expresses and brings to life) Emma’s moral content. So the form of a well-made work of art is integrated with its content: the two become indivisible. To clinch this claim I shall offer one further piece of evidence: namely, Picasso’s mural-sized painting Guernica (1937).

Guernica is the name of a Basque town in northern Spain, a bastion of Republican resistance during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). On 26 April 1937 Guernica was bombed for two hours by Nazi German and Fascist Italian warplanes at the request of the Spanish Nationalists, who were fighting to overthrow both the Basque government and the Spanish Republican government. The town was devastated and according to the official Basque figures, 1,654 civilians were killed.

Picasso (who was born in Spain) painted Guernica to commemorate the horrors of the bombing. It is a work that certainly enacts its moral valuation. It is impossible to make a purely formalist evaluation of Guernica because one could not set aside its ‘content’ (the anger and the pity it projects) without destroying it as a work of art. Picasso explained that the painting was inspired by his “abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain in an ocean of pain and death”: he produced it as a ‘weapon’ in a war against Fascism. [Picasso’s Statement, 1937] Guernica was his instrument of war; and Triumph of the Will was Hitler’s instrument in the mobilisation for war. They are committed works, engaged as opponents in a battle, and both should be judged as such.

My reasoning leads me to two conclusions. First, that there is a connection between the artistic value of works of art and the moral attitudes of those who bring them about, which includes those who inspire and commission art, as well as those who actually make it. Secondly, this connection is necessary, not contingent. This necessity isn’t of the logical kind, but an ‘intrinsic’ sort of necessity, one that it is inheres in the work.

How (in the light of these conclusions) should the fact that Triumph of the Will is evil feature in our evaluation of it as a work of art? The film clearly is of artistic value. Mary Devereaux called it “extremely powerful, perhaps even a work of genius.” But despite its mastery we must condemn it because it serves (is indeed ruled by) a vile vision. Its vision is vile because it lies about the real nature of Nazi Germany: it presents as beautiful and good things that are categorically evil, namely Hitler and National Socialism. It is impossible to ignore this fact when we evaluate Triumph of the Will as art, because the film’s vision is essential to it being the work of art it is.

We have seen that the purely formalist approach to a work of art which raises moral issues is to sever aesthetic evaluation from moral evaluation, and to assess the work in aesthetic (i.e., formal) terms alone. This is impossible in judging Triumph of the Will, because the evil quality of its content is (to use Leavis’s word) ‘enacted’ by its form.

I have taken the following path to reach a judgement of Triumph of the Will:

(1) Every detail of the film contributes to its moral vision.

(2) This vision is essential to the film being the work of art it is.

(3) Therefore, if the film’s vision is flawed, then so is the film as a work of art.

(4) The film’s vision is flawed. It attracts us to evil by rendering it beautiful.

(5) Therefore, the film is flawed as art.

The film’s content is inextricable from its form, and therefore it is impossible to judge the formal elements in isolation from the vision they instantiate. The beautiful vision of Hitler and Nazi Germany is the soul or essence of the film, the property that makes it the work of art it is. Hence in watching it, it is impossible to disregard or to disengage or distance oneself from that vision. Therefore the film is bad as art.

© Stuart Greenstreet 2019

Stuart Greenstreet was awarded a diploma in Philosophy by Birkbeck College, London. After graduating from the OU he also studied philosophy at the University of Sussex.