Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

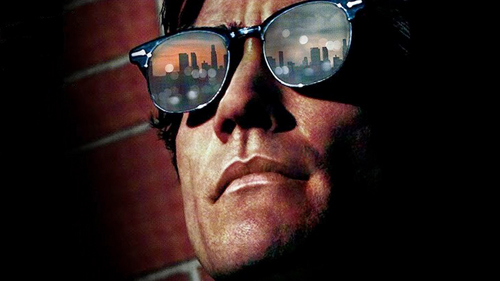

Nightcrawler

Terri Murray watches the disappearance of reality into images, in the name of news.

Nightcrawler (2014) belongs in the canon of classic films about the power of representation and the insidious effects of the media, alongside such prescient movies as Network, Medium Cool, They Shoot Horses Don’t They?, Putney Swope, Ace in the Hole, Man Bites Dog, Wag the Dog, Face in the Crowd and Death of a President. The medium is the message in this dark satire about how abysmally low the media will stoop for a scoop. The viewer is made to reflect upon the forces driving the ‘infotainment’ industry that has all but replaced serious journalism. Let’s take a look.

Nightcrawler images © Open Road Films 2014

The Presentation of Self & World

Director/writer Dan Gilroy’s screenplay is genius, and Jake Gyllenhaal and Rene Russo are at their best as sleazy, compromised anti-heroes.

If you emerge from the cinema wanting to reflect further on Gyllenhaal’s character Louis Bloom, may I recommend the work of Canadian-American sociologist Erving Goffman (1922-82)? I’m thinking particularly of his account of people not as ‘inner selves’, but as performers in social situations. Goffman’s key concern was not ‘authenticity’, but how our various performances promote our social survival, or not. In his 1959 book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman suggested that image management forms the basis of our behaviour. He divides life into ‘on stage’ and ‘back stage’ moments, and sees people as actors. The self is dependent on its ‘dramaturgical’ relationship to the social nexus of institutions, through roles that will be credited or discredited. As such, our self is a result of the façades we erect for different audiences. It is an effect, not a cause, arising from the scenes of our lives. This way of thinking about the self is reflected in Nightcrawler.

Lou Bloom is a hustler who makes his living from deceptive self-promotion. His primary skill, and the key to his success, is persuading people that he already possesses abilities which in reality he will gain only if they believe him and invest in him. He sells them an illusion; but in doing so the illusion becomes real. And just as Lou constructs a self from the fictional persona he pushes, he also brings into being a set of real effects from the media illusion he sells.

Transformation by means of self-fulfilling prophecy is a leitmotif humming beneath all the events depicted, including Lou selling himself as a roaming reporter/cameraman (a ‘stringer’) to Nina (Russo), the News Editor at KWLA, and his ‘I run a successful TV news business’ spiel when hiring his assistant Rick (Riz Ahmed). Lou needs the assistant to make his business successful, and by convincing him that his business is already successful, he gets the outcome he wants: the youngster takes the job. Lou isn’t the only one at it; his competitor offers to bring him in to a company that doesn’t yet exist – but would if he could get Lou on his team.

It’s all image. In each case the pretence of some situation being better than it is in reality is used to bring the better situation into reality. If this works for aspirations and ambitions, then it also works for fears and nightmares. Goffman’s emphasis on the ‘façade self’ has its parallel in the view of contemporary culture as a world full of images and simulations. Lou needs sensational and gruesome footage to get the ratings, so he invents it. At first he merely uses clever editing to heighten the viewer’s sense of personal tragedy and loss, giving the content more emotive appeal. Later he actually interferes with the world he’s supposed to only be recording, by posing and even moving corpses for better camera angles and more dramatic effect.

What’s most disturbing about Lou’s behaviour is that he chooses to exploit victims of crime when he could put down his camera and help them. Instead, he transforms their suffering and misfortune into a cash cow, thus feeding on other peoples’ misfortune, prolonging it, expanding it, and intensifying it. This worsens the victim’s situation, perverts and demeans Lou’s own humanity, and creates an appetite for bad news and schadenfreude in his viewers. The sheer volume of human misery and violence he serves up probably desensitises the public to suffering as much as it has done to Lou himself. Not only does the subject change in front of the camera like a gory version of quantum observation changing reality, the cameraman is also transformed, into a blood junkie hankering after an ever more potent fix. In all these ways the production of broadcast news by reporters obsessed with violence and tragedy results in an altered reality – a culture fashioned in the image of the media content it consumes. In convincing others to believe in his illusions and false ‘realities’, the broadcaster nurtures their wildest fantasies and nightmares. As Lou says, “You know what FEAR stands for?… False Evidence Appearing Real.”

Nightcrawler makes us question how far today’s media are transforming the world as opposed to merely reflecting or observing it. The consensus among media scholars is that a ‘hypodermic’ (or we might say ‘direct injection’) model of media effects overestimates the power of the media to shape perceptions and behaviour. Nevertheless, the weight of evidence from dozens of studies supports the view that exposure to media violence does lead to aggression, desensitization toward violence, and lack of sympathy for its victims, particularly in children. The US Surgeon General’s Office, the US National Institute of Mental Health, and many professional organisations around the world, consider exposure to media violence a risk factor for actual violence.

Lou rearranges some props for a shoot

The Unreality of the Presentation

All of this gives new relevance to the work of French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007). Baudrillard, even before the birth of the internet, used to emphasise that we inhabit a world engulfed by constant and pervasive images, or what he called ‘hyperreality’. He explored how the media transform the reality that most of us take for granted as being separate and distinct from mere images or representations of it. For example, in The Evil Demon of Images (1984) Baudrillard explained how images have ‘imploded’ into the real world. Now images precede and shape reality. This reverses the conventional causal relationship between reality and the image. One of Baudrillard’s core arguments was that our world is so thoroughly saturated with mediated images of it that there’s no longer any way to access a real world untainted by this flux of appearances. Our experience of the world is filtered through preconceptions and expectations that are products of media culture; and in a world saturated with reproductions, representations, and imitations, it becomes very difficult to conceptualise a ‘pure reality’ to which we can contrast the myriad of simulations. Simulations have imploded into us, into our behaviour, our bodies, our buildings, our procedures, and our environment, such that our real world is regulated by simulation. The arrow between the real and the representation seems to have been reversed: now ‘reality’ is an effect of media culture, rather than culture springing from something prior to and deeper than it. Instead of art imitating life, life imitates art.

In his 1923 book Crystallizing Public Opinion, the Austrian-American public relations and propaganda pioneer Edward Bernays (1891-1995) wrote that the PR executive’s most valuable asset is a capacity for crystallizing the obscure tendencies of the public mind before they find expression. The propagandist must tap into instincts and emotions that already exist in order to extract the desired responses and reactions; he cannot create reactions out of thin air. His job is more akin to directing the public towards, or deflecting them from, certain aims or goals. By framing the facts in particular ways, he is able to change their significance to his audience.

In explaining the method by which propaganda works, Bernays said that news receives attention in the competitive marketplace by virtue of its ‘superior inherent interest’. Therefore, the PR executive must “lift startling facts from his whole subject and present them as news. He must isolate ideas and develop them into events so that they can be more readily understood and may claim attention as news” (p. 171). In just this way, Nightcrawler’s Nina sees how connections between separate events can be woven into a tapestry that makes them more ‘newsworthy’ (that is, more sensational): “Tie it in with the carjacking last month in Glendale and the other one, the van in Palms, when was that? March. It’s a carjacking crime wave. That’s the banner. Call the victim’s family. Get a quote. Mike it. You know what to do.” Meanwhile Lou wants to move up the corporate ladder into the editorial side of the business. He is acutely aware that the most sensational and graphic content will ‘cut through’ and boost the network’s market share: “I don’t think it’s any secret that I’ve single-handedly raised the unit price of your ratings book,” he tells Nina. In his 1928 book Propaganda, Bernays explains how news is as much made as it is captured:

“In the selection of news the editor is usually entirely independent. In the New York Times – to take an outstanding example – [the editors] determine with complete independence what is and what is not news… The fact of its accomplishment makes it news. If the public relations counsel can breathe the breath of life into an idea and make it take its place among other ideas and events, it will receive the public attention it merits” (p.150).

We can glean parallels between what Bernays says about the role of the newspaper editor and Nina’s job as a television news editor. Her constructing the news is given its most literal exposition in the ‘horror house’ segment of the movie, in which Nina tells her anchor literally to “build it!”

Nightcrawler persistently reminds us how the propagandist fulfils his client’s aspirations by turning fantasies into ‘reality’. Looking at a fake backdrop of the Los Angeles skyline at the television station, Lou says to Nina, “On TV it looks so real.” Gilroy’s dialogue often cleverly insinuates this seeping of fiction and fantasy into a world that resembles them:

Lou: I’m focusing on framing. A proper frame not only draws the eye into a picture but keeps it there longer – dissolving the barrier between the subject and the outside of the frame.

Nina: Is that blood on your shirt?

‘Framing’ is a central trope in Nightcrawler. By invading the home of a family struck by tragedy, and zooming in on a family photo stuck to their fridge, Lou reframes the otherwise common event into ‘good television’. He quickly learns how the editors at the station construct the story to maximum effect by linking the intimate details he has recorded to the loss they’ve suffered, thus turning anonymous victims into ‘relatable characters’.

A cinematic vision of fake news, including a mirror image of a fake city

Reporting Tragedy or Causing It?

But this is just a movie. How closely does this fiction reflect the activities of real media organisations? Dateline NBC’s To Catch a Predator reality TV program provides a vivid example of how a network blurred the line between journalism and entertainment, and between reporting events and causing them. The show sought out online predators such as paedophiles and lured them to meetings that would end with their arrest. Its sting operations caught dozens of people. The irony, said critics, was that the network acted in a predatory way itself. Its set-ups seemed likely to have made criminals out of at least some people who had merely flirted around the edges of illegal activity until being coaxed into actually committing illegal acts by the show’s actors. Crime makes good television; potential crime doesn’t.

In the most notorious case, the network used an underage-looking actor to entrap a small-town Texas Assistant District Attorney called Bill Conradt. The network involved the otherwise bored local police force – a role they were apparently only too excited to assume, since it gave them national attention. With the cops functioning as its de facto actors, the network then decided to do something unprecedented. Since Conradt was no longer responding to their actor’s online solicitations, the TV crew persuaded local law enforcement to call in a SWAT team! With NBC’s camera rolling, the police broke into Conradt’s home. Facing public shame and under the intense duress of the situation, Conradt put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. NBC, with all the sensitivity of a dentist’s drill, broadcast the segment during prime time. The presenter of To Catch a Predator said Conradt’s suicide was something “nobody can feel good about”, but expressed no regrets about the overall handling of the operation. Conradt’s family sued. Some of the men caught in the show’s sting operations, however, admitted to previous criminal activity. In this way the show’s illusions sometimes revealed realities. As in Nightcrawler, illusion and reality alternated in a fast, close dance.

Unlike the usual escapist offerings at the cinema, Nightcrawler has an ‘alienating’ effect, insofar as it forces us to think about the media and the entire system within which it is made, rather than just taking it for granted. In the same sense that Bertolt Brecht’s epic plays are revolutionary theatre, Nightcrawler is a truly revolutionary film, for it provokes viewers to question their social conditions and what it means to consume media.

© Terri Murray 2019

Terri Murray is the author of Feminist Film Studies: A Teacher’s Guide. She earned her BFA degree in Film & Television Studies from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, and has taught A-Level film studies for 15 years.