Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Religion & Secularism

Einstein & The Rebbe

Ronald Pies sets up a dialogue between science and religion.

“The Bible shows the way to go to heaven, not the way the heavens go.”

– Galileo Galilei

“There is no harmony between religion and science. When science was a child, religion sought to strangle it in the cradle.”

– R.G. Ingersoll

When I was a resident in psychiatry, over thirty-five years ago, one of my mentors said something that forever changed the way I thought about my profession. “In psychiatry,” he said, “you can do biology in the morning and theology in the afternoon”. He was being a little facetious, but on a deeper level he meant what he said. I understood his message to be simply this: the problems of my patients could be understood and approached from both a ‘scientific’ and a ‘religious’ perspective without fear of contradiction or inconsistency. Yes, I know there are many critics of psychiatry who would challenge its scientific bona fides, but that’s a debate that would take me too far afield. Instead, I would like to use my teacher’s claim as a point of entry into a much broader question: namely, in what ways do science and religion differ, and in what sense do they have features in common?

This is hardly a new question, and I don’t claim to have any revolutionary answers. But I hope that by distinguishing between the truth claims and the wisdom claims of science and religion I can make the case for a form of ‘compatibilism’. To do this, I will draw out St Augustine’s distinction between scientia and sapientia, whose meanings I will try to make clear presently. In addition, as an illustration of how this distinction may be helpful, I will present an imagined dialogue (albeit using real quotes) between two towering figures in the realms of science and religion, Albert Einstein, and Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, known as ‘the Rebbe’. What makes this dialogue different from the usual ‘Science vs. Religion’ boxing match is the eclectic and nuanced positions of the two figures, for in an important sense Albert Einstein was a deeply religious scientist, and the Rebbe a deeply scientific theologian.

A Tale of Two Terms: Science & Religion

When considering the commonalities and differences between science and religion, it seems useful to proffer at least some rough-and-ready working definitions of them. I don’t claim that these definitions provide necessary and sufficient criteria for either of the term’s ‘science’ or ‘religion’. Indeed, Ludwig Wittgenstein taught us to question the very notion of such ‘essential’ definitions. Yet we must begin somewhere. Accordingly, I would like to define ‘science’ as ‘That field of study which attempts to describe and understand the nature of the universe, in whole or in part, by means of: careful observation; hypothesis formulation; empirical attempts to verify and falsify hypotheses; and experimental tests of predictions generated by specific hypotheses’.

Defining religion is perhaps even dodgier than defining science. As Professor of Religion Thomas A. Idinopulos has noted, “The more we learn about religions, the more we appreciate not their similarities but their differences” (‘What is Religion?’, Cross Currents, 1998). (I’m also reminded of the satirical definition in Henry Fielding’s 1749 novel Tom Jones: “By religion I mean Christianity, by Christianity I mean Protestantism, by Protestantism I mean the Church of England as established by law.”) Nevertheless, I want to venture a working definition of religion based in part on the work of the philosopher Ninian Smart (1927-2001). In my view, ‘religion’ may be defined, very roughly, as ‘That body of beliefs, rituals, values, norms, and narratives that address the place of humankind in relation to the universe, and proffer a coherent worldview in which faith, devotion, a sense of the sacred, and adherence to ultimate values, play an important role’. Note that this definition of religion does not require belief in a deity – including an omniscient, omnipotent Creator who intervenes in the affairs of mankind – although it does not preclude God or gods, either. Indeed, if you consider Buddhism a religion, the concept of a transcendent deity is not found in Theravada Buddhism, and is only partly expressed in some strains of Mahayana Buddhism. Jainism, too, lacks any well-formed notion of a deity. So when we ask whether science and religion share certain attributes, we need not do so in relation to any of the notions of God as understood in, for example, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

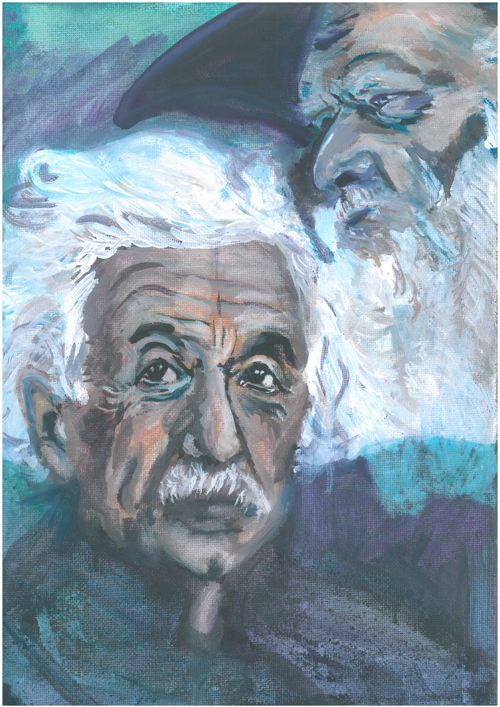

Einstein & The Rebbe by Gail Campbell, 2020

Compatible or Incompatible?

As suggested by the dueling epigrams at the beginning of this article, there is a yawning chasm between two extremes of views of religion’s relation to science. Galileo presented a ‘compatibilist’ view, suggesting, in effect, that religion tells us what we must do to attain salvation, not how the stars and planets operate under natural law. The latter is the province of science. This position is not far from that of the late Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002), who coined the term ‘non-overlapping magisteria’ to describe the relationship between science and religion. As Gould succinctly put it, “The net of science covers the empirical universe: what is it made of (fact) and why does it work this way (theory). The net of religion extends over questions of moral meaning and value. These two magisteria do not overlap” (taken from the Gould website).

In stark contrast, we have the ‘incompatibilist’ view of the American lawyer R.G. Ingersoll (1833-1899), known as ‘the Great Agnostic’, who argued that religion and science are in effect mortal enemies. But his claim that religion has been unequivocally hostile to science could be disputed through several archetypal historical examples. For instance, in the infamous Galileo affair, in which the Catholic Church ultimately condemned Galileo for heresy, it is not clear that the Church’s initial opposition was purely due to it having ‘anti-scientific’ attitudes. Some scholars have suggested that Cardinal Bellarmine, the head of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, “was willing to countenance scientific truth if it could be proven or demonstrated” to his satisfaction. (A full discussion of this is provided by P. Machamer in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2014.)

In contrast to Gould’s position I’d like to argue that there is a limited but important degree of overlap between science and religion. I’d also like to argue, in contrast to Ingersoll that religion need not be an enemy of science. But before unpacking my ‘modified compatibilist’ position, I would like to present a hypothetical dialogue between two immense historical figures in the magisteria of science and of religion.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) is arguably the most renowned scientist since Isaac Newton, while Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-94) was the head of the Lubavitcher branch of Orthodox Judaism. But the Rebbe was no ordinary man of religion, as he had studied science and mathematics at the Humboldt University of Berlin and the Sorbonne. He was quite capable of discussing science intelligently, even with the likes of Albert Einstein. For his part, although Einstein had been brought up in a non-observant Jewish household, he “had great respect for the humanistic elements in Jewish tradition”, and retained from his childhood “a profound reverence for the harmony and beauty of what he called the mind of God, as it was expressed in the creation of the universe and its laws” (Einstein: His Life and Universe, W. Isaacson, p.20, 2008). This point becomes crucial in the argument I’ll develop.

The Rebbe Meets Einstein

Let’s imagine a meeting in Professor Einstein’s study in late 1954, shortly before the scientist’s death. Einstein would have been seventy-five years old; the Rebbe around fifty-two. Although the dialogue is hypothetical, Einstein’s views are represented by verbatim quotes from Einstein himself over the span of many years. In the case of the Rebbe, the quotes represent the teachings of Rabbi Schneerson as memorized and collated by a group of ‘oral scribes’. The collated teachings were then transcribed by the Rebbe’s student-disciple, Rabbi Simon Jacobson. I have also added a few informal greetings and transitional remarks, shown in italics. Moreover, although the dialogue is shown in English, one can easily imagine the two men conversing in Yiddish, the mother tongue of many Jewish people around the world:

The Rebbe: Greetings, Herr Professor! It is an honor to meet you! So, if I may be so bold, here is the problem. For some people, there still exists today a rift between science and religion, as though some parts of life are controlled by G-d and others by the laws of science and nature. This compartmentalized attitude, however, is wrong. Since G-d created the universe and the natural laws that govern it, there can be no schism between the creator and His creation.

Einstein: Rebbe, it is a pleasure to meet you! I would say that behind the discernible laws and connections there remains something subtle, intangible, and inexplicable. Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion. To that extent, I am, in fact religious. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it.

The Rebbe: Indeed, Herr Professor! And the natural laws of the universe can hardly contradict the blueprint from which they were made! So, science is ultimately the human study of G-d’s mind, the search to understand the laws that G-d installed to run the physical universe.

Einstein: Yes, Rebbe, though I cannot conceive of a God who rewards and punishes his creatures, or has a will of the type of which we are conscious in ourselves… Enough for me [is] the mystery of the eternity of life, and the inkling of the marvelous structure of reality, together with the single-hearted endeavor to comprehend a portion, be it ever so tiny, of the reason that manifests itself in nature.

The Rebbe: Indeed, Herr Professor, there is no question that the universe is guided by a certain logic… Scientists and philosophers peer through the outer layers of the universe to discover the force lying within. What we are all actually searching for, whether or not we acknowledge it, is G-d, the hand inside the glove.

Einstein: You know, Rebbe, I think we are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn’t know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being towards God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws, but only dimly understand these laws.

The Rebbe: So the true challenge of science today is not to refute G-d, but to discover how [science] reflects and illuminates parts of G-d’s mind that have yet to be uncovered.

Einstein: For me, Rebbe, the most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and science… To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is something that our minds cannot grasp whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly: this is religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I am a devoutly religious man.

Truth Claims & Wisdom Claims: Scientia & Sapientia

There are clearly some truth claims in science and in religion that simply cannot be reconciled. For example, whereas some Christian fundamentalists calculate the age of the Earth as just over six thousand years, most scientists believe the correct figure is about 4.6 billion years. Assuming, both claims are using the word ‘year’ in the same way, then there is simply no way they can be reconciled. Moreover, the methods of religion and science are also radically different, if not broadly incompatible. For example, we do not generally find theologians conducting controlled experiments to determine the age of the Earth or to find out whether their prayers are answered. However, when it comes to wisdom claims, there are areas of significant compatibility between science and religion.

Some derivations of the word ‘religion’ relate it to the Latin religare, meaning ‘to bind fast’ or ‘to connect’. I would argue that religion, as I have defined it, seeks to connect us, as human beings, to the underlying and ultimate ‘Originating Force’ responsible for our existence, whether this is ‘God’, ‘Brahman’, ‘the Dao’ or something else. Science similarly seeks to connect us to the cosmic order, albeit in a material sense. When Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young sang in ‘Woodstock’ that “We are stardust, we are golden, we are billion year old carbon”, they were merely reflecting the prevailing scientific claim, best expressed in 1973 by astronomer Carl Sagan on the TV show Cosmos, that “the iron in our blood, the calcium in our teeth, the carbon in our genes, were produced billions of years ago in the interior of a red giant star. We are made of star-stuff.”

A more spiritualized version of this idea was expressed in 1918, by the then-President of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Dr Albert D. Watson:

“It is true that a first thoughtful glimpse of the immeasurable universe is liable rather to discourage us with a sense of our own insignificance. But astronomy is wholesome even in this, and helps to clear the way to a realization that as our bodies are an integral part of the great physical universe, so through them are manifested laws and forces that take rank with the highest manifestation of Cosmic Being.”

(Retiring President’s Address, Annual Meeting, January 29, 1918, italics added)

It should be clear that the italicized portion of the statement is not an assertion of scientific fact; that it is not a verifiable truth claim, like ‘The half-life of strontium-90 is 28.8 years’. Rather, it asserts a fundamental relationship between our bodies as physical entities and ‘the highest manifestation of Cosmic Being’ (the capital letters were doubtless important for Dr Watson). I would characterize this as a wisdom claim – not unlike the claim of Einstein when he said, “behind the discernible laws and connections there remains something subtle, intangible, and inexplicable.”

The distinction I wish to emphasize here, between truth claims and wisdom claims, is also far from novel: I am drawing on the distinction Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) made sixteen centuries ago, between scientia and sapientia. For Augustine, scientia denoted ‘knowledge of temporal things’ – what we might call ‘facts about the observable world’. In contrast, sapientia denoted ‘wisdom derived from the contemplation of eternal truth’ (‘Augustine of Hippo’s Trinitarian Imago Dei For Balancing Intellect and Emotion In The Life of Faith’, Jerry Ireland, 2013).

I believe that much apparent disagreement between science and religion stems from a failure to distinguish these two distinct modes of knowing. Indeed, mistaking a scientia statement for a sapientia statement (or vice versa) would be what the philosopher Gilbert Ryle called a ‘category mistake’ – roughly speaking, a bit like calling a whale a fish.

For example, in the Passover Haggadah – the guide to observing the Passover meal – we read the following:

“It was not just our fathers and our mothers who were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt; but we, all of us gathered here tonight, were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt”

It is nonsensical to read this statement as belonging to the category of scientia. It is quintessentially a statement of sapientia, or wisdom. As Prof. Marcus Borg explains, “the exodus story is understood to be true in every generation. It portrays bondage as a perennial human problem… [and is] thus a perennially true story about the divine-human relationship.” (Reading the Bible Again for the First Time, 2001, p.49). Moreover, as Borg points out, many sapientia statements in religious texts are essentially metaphors, and as such, only appear to contradict scientific statements about the observable world. The danger emerges when we literalize what are essentially metaphorical statements. It is important to note (as Borg does) that metaphorical statements are not false statements even though they are not scientific statements. They may still contain important wisdom. Indeed, Borg observes that “metaphors can be profoundly true, even though they are not literally true. Metaphor is poetry plus, not factuality minus” (p.41). For example, in John 15:5, Jesus tells his disciples, “I am the vine, you are the branches. He who abides in me, and I in him, he it is that bears much fruit.” Clearly, this extended metaphor is not a literal claim about observable facts that can be tested and contradicted by science. Rather, it is a wisdom statement – a metaphor expressing the idea that Jesus’s followers are spiritual extensions of himself, and that good things will come of their faith.

A Personal Coda

I have a strange ritual I perform every morning, based very loosely on a Jewish prayer called the modeh ani, which is traditionally recited upon first awakening. It’s a prayer of thanks. In English it says, “I offer thanks to You, living and eternal King, for You have mercifully restored my soul within me; Your faithfulness is great.”

Why do I call my ritual ‘strange’? In short, because I am not at all sure that there is any ‘eternal King’ listening to me, much less that such a Cosmic Ruler would care one whit about my needs, wishes, or aspirations. And yet, each morning I give thanks for life and health, and speak as if some ‘higher power’ could hear me. My prayer is not scientia. It is not a statement of fact, susceptible to scientific refutation. It is an act of consecration – an act ‘dedicated to a sacred purpose’. It is religious, in so far as my giving thanks connects me to something larger than myself, perhaps in Einstein’s sort of sense. My prayer does not quarrel with science: it presents no challenge to my scientific or medical knowledge. Rather, such an act of consecration is a gesture toward sapientia, a seeking of wisdom – even in the face of the deepest doubt.

© Ronald W. Pies MD 2020

Ronald Pies, Professor of Psychiatry at SUNY Upstate Medical University and Tufts University, is the author of The Three-Petalled Rose, and other books of philosophy.

• The author wishes to thank Roger Price for his support of this work.