Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Why We Are in Need of Tails by Maria daVenza Tillmanns

Philosophy is child’s play this issue, as Sergey Borisov explores the existential need for commitment using tails.

Before me lies a wonderful book with the mysterious title Why We Are in Need of Tails. The book is a short story for all ages by the philosopher Maria daVenza Tillmanns, accompanied by illustrations by the artist Blair Thornley.

Tillmanns teaches philosophy with children in a program developed in collaboration with the University of California at San Diego. She’s a professional philosopher with her own unique style for whom philosophy is an artform, and says she likes to ‘paint with ideas’ (p.35). The talented artist Blair Thornley has embodied these ideas in her distinctive illustrations.

In Why We are in Need of Tails, Tillmanns explores our existential need for connection in a whimsical, playful way. So what’s this book about? How did its author manage to put big philosophy into one small story?

The characters Huk and Tuk in the book express and symbolise their friendship by interlinking their tails. The book puts across that ties of friendship, though strong, enhance our freedom. These ties should also be organic; they should be natural, not artificial.

Images © Blair Thornley

It is a pity that we rarely have a magical ‘tail’ that connects us to another’s presence in our lives. Over time, many artificial devices for the convenience of our lives have made these tails (strong personal connections) seem less necessary, and they have gradually atrophied. Only now has the scale of that catastrophe became clear. Communication lost its subtlety and precision. Where previously only the tail (the intimate connection) was enough to communicate, now it takes hundreds of words to convey or express the same thing, and we still cannot always achieve our goal. We can be heard, but we are not always understood. Without tails – without our ties of friendship – we cannot pass on to another person the full depth of our feelings and thoughts. We can be there for each other, but there’s something missing: we feel disconnected, distant from the Other somehow. Tillmanns however, suggests a cure for this awkwardness. We are helped to communicate by metaphors, images, and everything that’s contained in wonderful tales. An allegory, a metaphor, a figurative vision, connects us with our invisible tails and our invisible roots. Through this subtle subconscious connection we feel unity with each other, because through these tales/tails we are rooted in culture, and so mutual understanding becomes possible.

All the winding paths of the vast body of the Earth, from its widest highways to the narrowest forest tracks, are like trails left behind by tails. And all paths, wandering and crossing, will lead you sooner or later to the same place – back home, home in this universe. So on a cosmic scale, it is not so important what road to take. Invisible connections are everywhere. For example, as the author of this beautiful story claims, string theory is a kind of tail-theory: Invisible strings permeate the Universe, forming spacetime fields. Everything is connected with everything through the intertwining of our ‘tails’ – the traces left by our physical interactions and the course of events. Everything is intertwined with and present to each other in different ways. Therefore, in every thing there is its opposite: a condition of transition and change creating a dynamic and pulsating whole, much like Yin and Yang. It’s all about keeping the world in balance.

By losing our tails – meaning, losing a direct connection with the world and other people – we also lose connection with ourselves. To feel connected to myself, I must be connected with the Other. Really connecting means that I feel the Other as I feel myself, and empathize with the Other. If I don’t do that, I may not think about how my desires will affect others and the world at large. I end up living ‘in the void’, wishing for something that cannot be. This becomes the root of forever-unfulfilled dissatisfaction. The lack of connection could also make me assertive and arrogant. My knowledge of the world without my deeper connection to it makes this knowledge not only arrogant, but foolish, and essentially unnecessary. Without feeling a real connection, I can project my own desires and thoughts onto another person, leading to me understanding them only in a vague and distorted way, if at all. The way to avoid this is to listen to the Other so that, as Tillmanns writes, ‘stereo listening mode’ is always on. Unlike the mono mode (which implies only our agreement or disagreement with the speaker), the stereo mode implies understanding the thoughts of others as the thoughts of a unique Other in all their dissimilarity and identity. When several voices are present in our mind at the same time, this creates a richer and more complete musical reality. Listening to these voices clearly, through understanding, means transforming the cacophony of individual sounds into a symphony of unified reality that resonates in people’s hearts and souls and becomes part of our individual and shared consciousness. This polyphonic listening provides an opportunity to penetrate aspects of reality inaccessible to superficial knowledge.

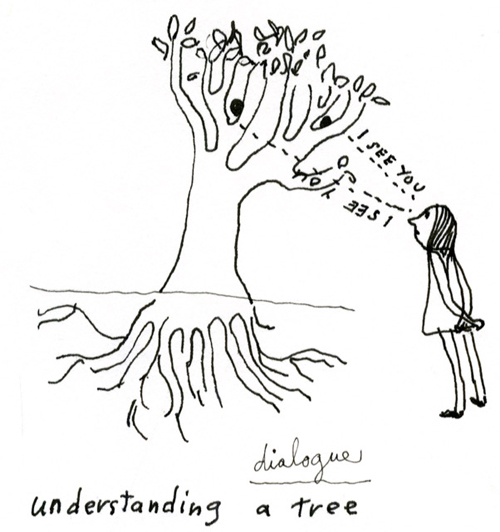

Tillmanns also shows us how to be able to properly connect to the symphony we hear. If you don’t have this skill, it’s like knowing music, but not being able to perform it. It’s knowledge without understanding. It becomes technical information, but doesn’t reach the soul. For another example, we may know a tree as a source of wood for building or as an object that creates a shady spot in a park; but understanding a tree is a different thing. To understand a tree is to understand the many things that make it possible to be a tree, which makes it unique and rooted, as it were, in reality. Its branched root system with its tails-roots provides a connection to the earth, and its crown with its tails-branches connect it with the atmosphere: “And so it is with everything else that was once connected and now so often lies fragmented and forlorn, not able to be part of the warp and woof of life” (p.17).

Often we know that something exists, but don’t understand how or why. We may see phenomena, but not understand how they are interconnected. We may know the patterns, but not grasp where they apply and where they don’t. We may know something about the world or people, but don’t comprehend what that knowledge is for. Only understanding makes us wise and receptive, able to be perceptive, that is, able to see the essence of things. Understanding makes me rich in what I will never lose. It is a wealth of meaning that is immense and inexhaustible. Most importantly, the acquisition of this wealth depends only on us, and no vicissitudes of fate can take it away from us. Understanding is an opportunity to reach out to everything with your tail and to establish a connection.

Another discovery that awaits readers of this book are the tails which create the possibility of meeting in the ‘in-between’, that is, in the relationship between people. According to existentialist and philosophical anthropologist Martin Buber (1878-1965), ‘being’ is to be in relationship or in relating. So you have to enter into a dialogue with reality, and through a tail-relationship the true nature of things is revealed. The tail-relationship brings the ‘I’ and ‘You’ to life in all things.

Buber (says the author) thinks it is possible to establish a relationship in the ‘in-between’ others only by using your whole being. Again, the metaphor of the tail clarifies this, because the tail is part of us. Of course, the loss of your tail will not endanger your life, just as the loss of your memory does not take away your consciousness, but there is an acute sense of disconnection from the world, of a lack of reliance, of separation. This feeling cannot be compensated for by technological or other artificial means. The thirst for a new, modern, advanced way of being in this world, has led us to lose our tails, our intimate connection with the Other. Has the ‘Post-Tail’ Age made us happier? Have people become kinder? Has society become fairer? Have people gained freedom? I’m afraid that each of these proposals is followed by a question mark’s tail. “We become just beings to be used for the sake of another being’s utility. We have to imagine we have tails in order to become whole again” (p.29).

Huk and Tuk impart valuable advice on how to reestablish lost connections in today’s world. They point to a love of the miracle of life – a love so deep it transforms into a deep trust, knowing that you belong to this world and that you are ‘already home!’ (р.34). It remains only to thank the author for an unusual and exciting journey into the world of big philosophical ideas.

© Dr Sergey Borisov 2021

Sergey Borisov is Head of the Department of Philosophy and Cultural Studies of the South Ural State Humanitarian Pedagogical University in Chelyabinsk. He is also Director of the Scientific and Educational Center for Practical and Applied Philosophy of the South Ural State University and President of Ratio, the Association of Philosophical Practitioners.

• Why We Are in Need of Tails by Maria daVenza Tillmanns, illustrated by Blair Thornley, Iguana Books, 2019, $12 pb, 35 pages, ISBN: 978-1771803908