Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Camus, The Plague and Us

Ray Boisvert on Albert Camus, Thomas Merton and a call to be a healer in a crisis.

Self-isolating and bored? Reading helps. Across the pandemic-tinged globe one book is flying off shelves: The Plague (1947), a novel by Albert Camus about a deadly epidemic in the Algerian town of Oran. If, as the saying goes, crisis reveals character, why not pick up a book whose central question is “What should I do?”

In a plague there is no avoiding the issue. Pretend there is no problem: that’s taking a stand. Remain neutral: that’s a choice. Profit from the crisis: that’s charting a path. Camus’s hero is Doctor Rieux. His answer: make an effort, help the healing.

Easier said than done. Avoiding responsibility is a major human sport, matched by the ability to concoct rationalizations. As a mid-20th century figure, Camus inherited the responsibility question as part of a wider framework: religion or nihilism, choose one. His take: they’re both bad. Each makes it easy to avoid responsibility.

The dilemma seems odd today. Religion should encourage responsibility. Nihilism, well, the very label has faded. It used to signal that life is objectively meaningless, and that all meaning is subjective. Although the word has faded, the perspective lives on in phrases like “it’s up to the individual,” “whatever floats your boat,” “don’t make value judgments.”

Albert Camus, 1957

Library of Congress

Camus wrote The Plague in a way that it would challenge the last pronouncement. Readers are led to make value judgments, to praise Rieux and the volunteers who combat the plague.

Here is where “it’s up to the individual” comes into play. It’s an expression with two separate meanings. The phrase, rightly, (a) emphasizes the personal dimension in choice. In a challenging situation, it’s up to the individual to select among options. So far so good. However, the fan of full-blown nihilism adds a second dimension. “It’s up to the individual” becomes (b) “whatever choice the individual makes is the right one.” To grasp the contrast, think of nutrition. It’s up to the individual (a) to decide which foodstuffs to ingest. It’s not up to the individual (b) whether those choices are healthy or not.

Camus challenged nihilism because of ‘b’. When ‘a’ and ‘b’ are run together, evaluations like “Dr Rieux’s actions are honorable” don’t mean much. “It’s up to the individual” translates into “That’s just your opinion.”

Why not, then, go with religion? For Camus, as for Nietzsche before him, religion just offers a disguised version of nihilism. The world is ‘fallen’, meaningless in itself. All values derive from divine commands.

Such an emphasis on God’s will bothered Camus. The Plague has a priest called Father Paneloux who delivers two sermons with standard themes: (1) “it’s a punishment for sins;” (2) “God works in mysterious ways.” As far as the doctor is concerned, such sermons carry dangerous messages: find scapegoats, welcome ignorance, accept God’s will, don’t roll up your sleeves and help.

Rieux realizes that despite bad theory, most religious individuals, in practice, go to a physician when ill. In this regard, Rieux has gotten surprising support. A real priest, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, agreed. Merton thought Camus was right to judge Father Paneloux’s sermons as “revolting.” It was appalling that the cleric would encourage his flock to “submit to a will we do not understand and even to adore and love what appears horrible.” Camus’s mistake, according to Merton, was believing that such an attitude is “essential to Christianity.” Idol worship is everywhere and even priests can worship false gods.

Merton provides a sort of mirror image of the ‘a’ and ‘b’ distinction as regards nihilism. What’s right is (a) acceptance of a divinity. What’s wrong is (b) the typical way that divinity is understood.

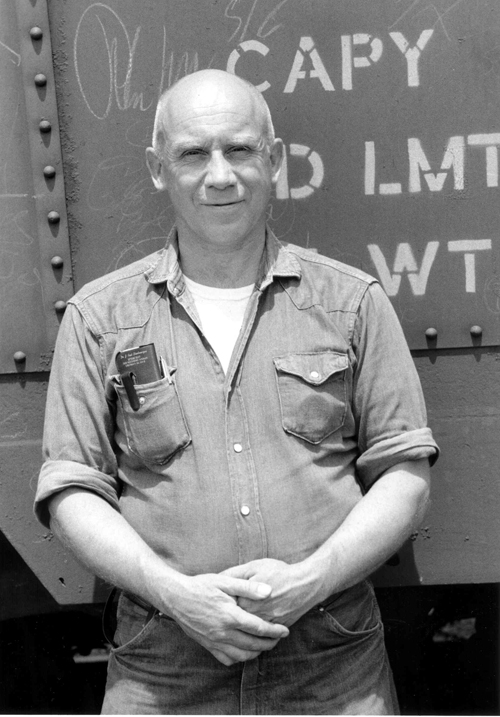

Trappist monk Thomas Merton (1915-1968). “[Father Paneloux thinks we should] submit to a will we do not understand and even to adore and love what appears horrible.” Literary Essays 212

Photograph of Thomas Merton by John Howard Griffin. Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center, Bellarmine University.

Camus had little patience for irresolvable ideological subtleties. His focus was on “What should I do?” His answer: become ‘true healers’. Become like doctors. Where there is illness, bring healing. Where there is suffering, bring relief. Churchgoers praying are not bringing relief. Nihilists, denying any deep meaning to the words ‘better’, and ‘worse’, are not sufficiently motivated. “What should I do?” Join the healers, do your part.

© Prof. Raymond D. Boisvert 2021

Raymond Boisvert is Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Siena College, Loudonville, NY.