Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Reality

Buddhist Metaphysics

Brian Morris describes four varieties of Buddhist metaphysics, and questions whether they can form one coherent system of thought.

Buddhism is often described as the philosophy of the ‘middle way’, in that the Buddha is alleged to have always urged his devotees to avoid ‘extremes’ in the quest for enlightenment – initially, the extremes of asceticism or self-indulgence.

Many scholars, like Sangharakshita, have emphasized that Buddhism is a form of ‘atheistic spirituality’ – a religion without a god – in that it attempts to steer a middle way between the theistic spirituality of the Hindu Vedanta tradition and the atheistic materialism of the Samkhya and Lokayata philosophies. But given the focal emphasis that Buddhism places upon the mind, its complete denial of a self, and the extreme idealist tendencies that developed within the Buddhist tradition, it is doubtful if Buddhism as a spiritual tradition ever took the middle way doctrinally. Indeed, many later Mahayana Buddhists, including such well-known figures as Daisetz Suzuki and Chogyam Trungpa, may best be described as advocating not a middle way between spirituality and materialism, but a form of mystical idealism. In this article I will offer some brief reflections on the Buddhist philosophical worldview, focussing on its diverse metaphysics, the implications for knowledge of its advocacy of transcendental wisdom (prajna), and the different strategies involved in its conception of enlightenment.

Although Buddhism has long been described as if it constituted a single coherent worldview, both the discourses of the Buddha and the writings of Buddhists throughout history have expressed worldviews that are complex and multifaceted. In fact, ‘the worldview of Buddhism’ (if it can be so called) is a rather heady mixture of four quite distinct and contrasting metaphysical systems. These may be called common-sense realism, theistic spirituality (a religious metaphysic), phenomenalism, and mystical idealism (or esotericism). I will discuss each of these in turn.

Common-Sense Realism

Buddhist philosophy is essentially focussed around five basic concepts: the three signs of being (ti-lakkhana), namely, impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and no-self (anatta); along with the concepts of dependent origination (patticca samuppada), and enlightenment (nirvana).

Although the concepts of impermanence and dependent origination are often described as if they were unique to Buddhism (or to Eastern spirituality more generally), in fact they were derived by the Buddha from a common-sense understanding of the material world. Not only Gautama the Buddha, but for example subsistence farmers in Africa, as much as people everywhere, are fully aware that all material things are transient and continually undergoing change: that things, especially living beings, including humans, come into being, grow and develop, age and decay, and finally pass away – cease to exist. People recognize the obvious fact that plants wilt without water, that wood rots, that streams run dry, that iron rusts, and that humans, as organisms, grow old and eventually die.

As common-sense realists, people also recognize that the world consists of a myriad of material things – the Daoist ‘ten thousand things’ – whether inanimate objects or living beings, and that everything is interrelated in complex ways, so that nothing is ‘self-existent’ or exists in complete isolation. Even the ardent egoist Ayn Rand recognized that she had to eat and breathe and otherwise continually engage with the world, both natural and social, in order to survive. The dynamic nature of the material world, namely that all things are transient and changing, and the interactions of all things (or events) is plainly evident to everyone as common-sense realists, including Buddhists. That material things are real, and have a reality independent of humans, and that (contrary to the arguments of Immanuel Kant) the nature of things and their relations can be known through sense perceptions and reason – all this is taken for granted by almost everyone as empirical naturalists. Apart from mystics, everyone recognizes the validity of common-sense empirical knowledge. Thus as the Buddha, as a common-sense realist, recognized – and as the early Buddhist school Pudgalavada strongly emphasized – the human person is not a disembodied ego, nor a conceptual ‘fiction’, but a real organic being, an embodied self with moral agency.

Theistic Spirituality

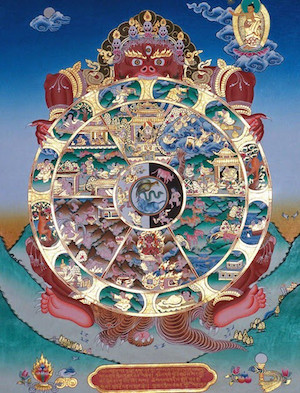

The Buddha, and his devotees throughout history, not only thought and acted as common-sense realists (like everyone else), they also embraced a religious metaphysic. In the Buddhist case this entailed the acceptance of a cosmological scheme consisting of six realms of beings in a sort of value hierarchy. There are various hells inhabited by malevolent spirits; a realm of hungry ghosts (pretas); the domain of animals; the world of humans; the abode of the demi-gods (asuras); and, finally, the heavenly realms of the gods (devas), enjoying a blissful life.

A theory of moral action (karma) and rebirth is intrinsic to this religious vision. These six realms are linked by an endless cycle (samsara) of rebirth, aging, and death. In Buddhist cosmology the concept of ‘dependent origination’ is also linked to the doctrine of karma and rebirth. It says that nothing comes into being or exists by itself independently, and therefore everything is liable to change and decay. This is demonstrated in the twelve links that comprise the ‘wheel of life’. Beginning with ignorance, this causal chain ends with old age and death.

To what extent this religious metaphysic is intrinsic to Buddhism has, however, long been debated among Buddhist scholars.

Phenomenalism

Aware of the apparent contradiction between the Buddhist concept of ‘no self’ (anatta), and the Buddha’s apparent ethical emphasis on the human subject as an embodied self with moral agency, some early Buddhists came out as phenomenalists. They had the notion of two realms of being, that of everyday life (laukika), and of a transcendental realm (lokuttara), which in turn was linked to the idea of two truths; the conventional truths of everyday life (our common-sense realism) (samvrti satya), and the absolute truths (paramartta satya). The latter truths are alleged to give us knowledge and experience of things ‘as they really are’. Under the latter perspective, not only are human beings in an absolute sense now alleged to be ‘unreal’ or as ultimately having no real (mind-independent) existence, so are all the material things and organisms that humans acknowledge and interact with in their everyday lives. We are thus informed by these Buddhists in accordance with this ‘phenomenalism’, that ultimately speaking, the substantive objects and enduring persons of everyday life do not exist: they are ‘fictions’ or ‘illusions’, or more specifically, merely constructs of the human mind. All material things are in this way mind-dependent, hence the label ‘phenomenalism’ (‘phenomena’ is Greek for ‘the things/experiences of the senses’). Buddhist phenomenalism is therefore a completely anti-realist metaphysic. What exists and has reality according to it are only fleeting mental events or moments of experience – described in the Abhidhamma as dhammas. This metaphysic is invariably linked by contemporary Western Buddhist scholars to the process theology of Alfred North Whitehead, or to the anti-realist subjectivism of postmodernist philosophy.

However, according to modern scientific knowledge, mental events and processes presuppose the existence and reality of material things. Thinking, for example, implies the existence of a bird or a mammal with a brain. Or a momentary event, such as the proverbial cat sitting on the mat, presupposes the real existence of the cat, the mat, the earth under the mat, as well as a real human observer of the event. So the phenomenalist contention of many Buddhists that all actions – digging, breathing, thinking, walking, dreaming, eating, defecating, and all the rest – are ultimately bereft of any person as an embodied self with causal agency, can be described as not only misleading but quite facile. It indicates an abandonment of the Buddha’s dialectical ‘middle way’ of understanding human experience through moderation.

Mystical Idealism

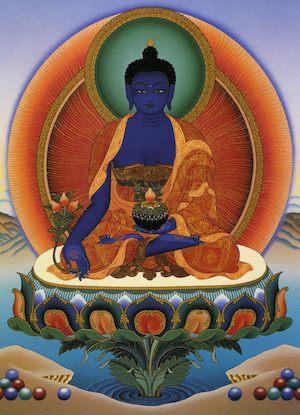

With the development of Mahayana Buddhism, the subjective idealism inherent in phenomenalism was taken to a further extreme, as Buddhists came to advocate a metaphysic of mystical or absolute idealism. This metaphysic was not only expressed by most of the iconic figures of Mahayana Buddhism – for example, Nagarjuna, Vasubandhu, Santideva, Huineng and Dogen – but also by more recent scholars such as Suzuki, Conze, Humphreys and Sangharakshita. For such mystical idealists, much as for the phenomenalists, the world of material things is described as ‘illusory’, as having no real existence, and empirical knowledge, which involves conceptual understanding built up from everyday sense experience, is continually denigrated, interpreted as implying a dualistic metaphysic of reality and illusion. Mystical idealism then comes to describe ‘things as they really are’ in a completely spiritual idiom. Going a step beyond phenomenalism, the ‘real’ world experienced in a state of enlightenment (nirvana) is described as empty or void (sunyata); as ‘mind only’, or as pure or foundational consciousness (alaya vijnana) without form. It is described by the following type of imagery: a sky devoid of clouds; an ocean, still without waves; infinite space; or as with Dogen, we’re like fishes swimming in water. Conflating reality with a type of human experience, reality is thence described by such epithets as the ‘absolute all-mind’; ‘non-dual consciousness’; ‘Buddha-nature’; ‘ground luminosity’; or the ‘cosmic self’. It is therefore hardly surprising that many Buddhist scholars have equated nirvana, as the experience of a ‘universal mind’, with such concepts as god, spirit, the divine, the Dao, or Brahman, of other mystical traditions. Many scholars have indeed equated this mystical idealism with the Buddhist way itself. As one Tibetan scholar-monk wrote, the Buddha “taught different philosophical systems according to the various needs and capabilities of his followers, but his intention was to lead all living beings eventually to the final view of the Madhyamaka-Prasangika School. There is no higher view than this” (Heart of Wisdom: Commentary to the Heart Sutra, Kelsang Gyatso 1986, p.36). This view suggests that what appears to us in everyday life, such as mountains, trees, and elephants, are purely ‘illusions’, devoid of reality, They are empty, void, unsubstantial: only the absolute mind is real.

Hardly a middle way!

The Ethics of the Worldviews

It is doubtful if the Buddha expressed any real interest in epistemology, nor was he really interested in understanding the material world and its rich diversity of life-forms in any sort of scientific sense. His concern – as he continually emphasized – was ethical: the understanding and alleviation of suffering.

It is however clear that the Buddha’s emphasis on ‘right views’ and on the cultivation of wisdom (prajna) has two very different interpretations. On the one hand it has an empirically-sourced meaning: wisdom is a result of understanding the impermanence of human life, and the fact that all things arise and cease to exist according to specific causes and conditions. For the Buddha, greed, hatred, and egoism invariably give rise to suffering. As with Aristotle, wisdom involves the application of empirical knowledge – about impermanence and conditionality – to ethics, thereby (for Aristotle) enhancing human flourishing and well-being, or (for the Buddha) enabling the alleviation of suffering with respect to sentient beings. There is, therefore, no alienation between empirical knowledge and practical wisdom. (It is also worth noting that what really ‘expands the mind’ is not the ingesting of psychedelic drugs, nor inducing some transcendental or mystical state through deep meditation, but empirical knowledge – contrary to even what most Buddhists think.) On the other hand, the ‘transcendental’ interpretation of wisdom has less to do with empirical knowledge and ethics than with the cultivation of a spiritual or mystical intuition, and the realization, through deep meditative states, that the world – reality – is pure empty consciousness or absolute all-mind.

It follows that both the experience and understanding of enlightenment within the Buddhist tradition has two very different kinds of meaning; either ethical (this-worldly) or metaphysical (other-worldly). Similarly, although Buddhist scholars invariably equate the concept of awareness or awakening (bodhi) with the experience of non-dual consciousness or emptiness (nirvana), awareness and emptiness imply two very different conceptions of enlightenment. Enlightenment as awareness suggests a common-sense realism. It posits that things in the world are transient and continually undergoing change, and that nothing is self-existent, in that all things are subject to specific causes and conditions. The human person as an ‘existing being’, to employ the Buddha’s own phrase, is no exception. The person as an embodied self is continually changing, and embedded in a complex web of relationships with both the natural world and with other people. Enlightenment as awareness thus entails a theory of knowledge that is historical, dialectical (that is, relational and dynamic) and this-worldly. Enlightenment in this sense occurs when an embodied self becomes fully aware of the truth that everything changes and that all things are subject to causes and conditions. Ethical conduct is here based on empirical knowledge, of the world as experienced in everyday life. It requires us to realize that suffering, along with sorrow and despair, arises from the three ‘poisons’, namely, greed, hatred and delusion – all egocentric strivings. And, as indicated, enlightenment as awareness also suggests a concept of wisdom akin to that of Aristotle; namely the application of empirical knowledge to the question of how to alleviate suffering, through the cultivation of wholesome mental states such as compassion, non-violence, generosity, and loving kindness.

In contrast, it appears that for many Buddhists – Daisetz Suzuki is a prime example – enlightenment as nibbana or emptiness implies a quite different worldview – that of mystical idealism. This involves the attainment of a state of mind that transcends the experiences of everyday life. This is a state of mind characterised as being unconditioned, eternal (or timeless), and empty (or disembodied). So here enlightenment is described as a form of non-dual consciousness that transcends both time and the material world of things. It leads to the understanding that ‘physical reality is created out of consciousness’ as one well-known scholar puts it (Bringing Home the Darma, Jack Cornfield, 2012, p.241). Enlightenment as nibbana therefore implies that ‘things as they really are’ are ‘mind-only’, as the ‘absolute all-mind’ or as the ‘cosmic consciousness’ beyond both the subjective mind and the body. For Suzuki, as for Nietzsche, it is a consciousness even beyond good and evil. This idea, however, appears to be completely at odds with the Buddha’s ethical philosophy.

Many contemporary Buddhists are dissatisfied with what they see as the overemphasis on meditation and the attainment of individual enlightenment. They have instead stressed the crucial need for a socially engaged Buddhism. This implies being directly involved in contemporary issues, specifically those relating to the ecological crisis and to social justice. It is also worth noting in passing that concepts of ‘no self’ and the ‘unconditioned’ were for the Buddha ethical concepts rather than metaphysical ones. They implied a rejection of egoism, not of the embodied self, and of seeking freedom from the unwholesome emotions of greed, hatred, and the craving for a permanent self.

It seems appropriate to conclude this article with Gotama the Buddha’s own words – for they succinctly express the Buddha’s dhamma – his teachings:

“But, friend, when you know certain things: these things lead to dispassion not to passion; to detachment not to bondage; to diminution not to accumulation; to having few wishes, not to having many wishes; to contentment not to discontent; to seclusion not to gregariousness; to the arousing of energy, not to indolence; to frugality not to luxurious living – of such things you can be certain.”

(Numerical Discourses of the Buddha: An Anthology of Suttas from the Anguttara Nikaya, Thera Nyanaponika and Bhikkitu Bodhi, eds, 1999, p.220).

Given the modern world, this vision still has relevance today.

© Prof. Brian Morris 2021

Brian Morris is emeritus professor of Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London.