Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

C.L.R. James (1901-1989)

David Austin on the life in writing of a philosopher of the dispossessed, and cricket.

Cyril Lionel Robert James was born in Trinidad in 1901. His father, Robert James, was a schoolmaster, but it was from his mother, Ida Elizabeth, a voracious reader, that he developed his love of literature, and especially of William Makepeace Thackery’s Vanity Fair, which he once claimed had more influence upon him than Marx. He began reading the Bible at age four, and later gravitated towards Ancient Greek literature. It was a central part of the elite public school curriculum in the colonial Caribbean, often taught by Oxford and Cambridge graduates. As he confessed in his semi-autobiographical philosophical study of cricket, Beyond a Boundary, “I believe that if when I left school I had gone into the society of Ancient Greece I would have been more at home than ever I had been since.”

CLR James by Gail Campbell 2022

James left Trinidad for London in 1932 to become a writer. He was quickly drawn into socialist and pan-African politics, both of which are embodied in his classic, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution (1938). As a work of political philosophy disguised as history, The Black Jacobins weaves across time and space, drawing on the revolution that led to Haiti’s independence in 1804 to illustrate his insights on the prospects of African and Caribbean liberation and world revolution. It does not simply describe the Haitian Revolution, but demonstrates its relevance for understanding the interplay of politics and freedom struggles on a transnational scale. The Haitian revolt was the first successful slave revolution in history. The dynamism of the enslaved Africans who organized themselves into an army that defeated the superpowers of their time – France, Spain, and England – is central to the book. As a masterpiece of literary non-fiction and political theory, The Black Jacobins is perhaps unrivaled. In James’ assessment of the slave plantation’s centrality to the development of global capitalism, the book anticipates the pioneering work of anthropologists Sidney Mintz and Richard Price.

At its core The Black Jacobins is a meditation on the dynamics of revolutionary politics. For James, so-called ordinary people possess the creative capacity to collectively organize themselves without the authority of leaders dictating from above the terms of their political existence. This vision is also evident in his debut novel Minty Alley (1936), long before he discovered Marx and Hegel, where James captures the sensibilities and mores of the people of the barrack-yard (tenements) in Trinidad. In this novel, ordinary people – in this case primarily Caribbean women – display the extraordinary creativity and persistence in the face of life’s challenges that’s exemplary of Caribbean culture.

It is near impossible to fully appreciate the artistic and political merits of James’ later work without having read Minty Alley’s vivid description of Trinidadian subaltern life. In the novel, the first major Caribbean work of fiction to be published in the UK, James captures the tensions among members of Trinidad’s underclass; and their capacity to endure, sustain a sense of dignity, and to persevere in the face of hardship. And like The Black Jacobins, Minty Alley embodies a dialectic of its own, rooted in James’ appreciation of the socio-cultural dynamics among ‘the people down below’.

James also translated Boris Souvarine’s Stalin from French to English during the late Thirties. This was one of the earliest major works to capture the totalitarian nature of Stalinism, and it later informed Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism. James’ 1937 work World Revolution: The Rise and Fall of the Communist International, 1917-1936 published just two years before Stalin, is a somewhat didactic assessment of international communism and the Soviet Union’s descent into totalitarianism. At the time, James was a devotee of Leon Trotsky, one of the architects of the Russian Revolution. In essence, from the mid-1930s till his break with Trotskyism in the 1940s, Trotsky was for James what Socrates was to Plato – both a teacher and a springboard. It was as a Trotskyist that James wrote both The Black Jacobins and World Revolution.

The tone of World Revolution is very much a product of the fractious politics of the pre-war 1930s. It was written only a few short years after James abandoned his literary aspirations for radical politics. It is not a classic, and yet it is remarkable for its rich detail and broad scope, covering as it does the trajectory of the Russian Revolution alongside the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy, the Spanish Civil War, and the Chinese Revolution. And anticipating ideas that he would later elaborate in State Capitalism and World Revolution, James illustrated how Soviet workers were politically manipulated and brutally exploited for their labour by the state. This was considered a heretical breach with not only conventional communism, but also the international Trotskyite position that Russia was a degenerated worker’s state but a worker’s state none the less.

James & Dialectic

World Revolution both anticipated and laid the foundation for Notes on Dialectics: Hegel, Marx, and Lenin (1948) – the book that James described as his most important. In it he lays out his socialist vision.

‘Dialectics’ – a form of logical argumentation in which two opposing ideas clash before combining into a new idea that contains elements of both – was central to the work of both Hegel and Marx. James wrote Notes on Dialectics in Nevada during a few manic months in 1948, ten years after the publication of The Black Jacobins and a hundred years after the publication of The Communist Manifesto. This was a trying time riddled with tensions within his political organization, and he lived with the constant threat of deportation (he had travelled to the U.S. in 1938 on a lecture tour and then overstayed his visa). He was also desperately attempting to secure a divorce from Juanita (nee Young) attempting to secure a divorce from Juanita (nee Young), whom he had married while still living in Trinidad, in order to marry the American woman who would become his second wife, Constance Webb. As James remarks in a letter to Webb from Reno, Nevada, he had not written so feverishly in some twenty years, about the time that he wrote Minty Alley, allegedly as part of a literary exercise for the great novel he hoped to write. Notes on Dialectics represents an effort to clarify his thoughts on socialist organization in the post-Second World War era by thinking through Hegel’s system of logic. In essence, the book represents his signature effort to redefine socialism away from the bureaucracy of the vanguard party (i.e., professional revolutionaries and revolutionary political parties in both communist and non-communist countries), which for James was an instrument of totalitarianism under Stalin.

Notes on Dialectics is in fact not a strict examination of Hegel’s logic, but an improvisatory interpretation of Hegel motivated by politics. Theodor Adorno once argued that, “In a similar sense to that in which there is only Hegelian philosophy, in the history of western music there is only Beethoven” (Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music, 1999). James too held Beethoven in high esteem, and wrote: “I have long believed that a very great revolutionary is a great artist, and that he develops ideas, programmes, etc., as Beethoven develops a movement” (Notes on Dialectics: Hegel, Marx, Lenin, 1980). In 1948 he certainly believed that Hegel’s system represented the ‘total philosophy’ captured in Adorno’s remark that “The will, the energy that sets form in motion in Beethoven, is always the whole, the Hegelian World Spirit.” Yet James was perfectly willing to take liberties with Hegel’s ideas. Referring to his fellow socialist philosopher Grace Lee, James acknowledged in Notes on Dialectics that “Grace is probably tearing her hair at the vulgarity of some of my illustrations” of Hegel’s logic. He was articulating the idea that, as a philosopher of politics, his goal was to creatively interpret Hegel’s thought in relation to his own object of study – socialism, and contemporary politics in general. James was not a professional academic but a political philosopher attempting to find the inner necessity of the socialist movement – as James himself suggests, in some ways akin to when St Paul was asked to demonstrate the inevitability and inner necessity of resurrection. Like Marx’s adaptation of Hegel’s dialectic to his analysis of capitalism and socialism in Capital and Grundrisse, James was looking for the historical logic of the socialist movement, that is, the forces and ideas that bring it into being and animate it.

For James, Hegel’s idealism was rooted in the material world: “If it is possible to say of Marxism that it is the most idealistic of materialisms, it is equally true of Hegel’s dialectic that it is the most materialistic of idealisms.” In other words, Hegel’s abstract philosophy was both emerging from and applicable to the material world and politics. Dialectic represented a way of being, seeing and understanding the world, and Hegel’s system of logic was more a product of creative imagination – art – than of science for James.

Notes on Dialectics takes James’ philosophical approach further than his previous work. He begins with a warning against holding fast to fixed, finite categories of ideas, then divides thought into the following groups:

1. Simple, everyday, common sense; vulgar empiricism; ordinary perception.

2. Understanding.

3. Dialectic.

The first category represents our intuitive everyday knowledge. The second, ‘understanding’, represents a higher form of knowledge which is nonetheless finite, fixed, and refuses to move, even when the object of thought has shifted or changed. So while understanding is crucial to dialectic, it can never be dialectic itself. James refers to the so-called ‘dialectic of notion’ as thought self-generated then elaborated. This captures the essence of dialectic in general, that is to say, of reason, which is infinite, continuous, and self-constitutive as it transcends categories of understanding in a constant movement of negation and sublation of the old ideas. In the process, dialectic forms new categories of thought that congeal elements of the old. This results in reason’s higher truths, in knowledge, or in forms of speculative thought.

James then proceeds to argue that the Marxist-Leninist vanguard party form of political organisation was rooted in the 1917 revolution, the implication being that it was outmoded by1948. In Russia the party had become a moribund organization within a totalitarian machine, which he describes as ‘state-capitalist barbarism’. In the USA, trade unions, though once considered an advanced form of political organization, were now the equivalent of the vanguard party within the labour movement – the bureaucratic equivalent of a totalitarian state. According to James, rather than facilitating the self-organization of workers, labor unions now facilitated their alienation, and even subjugation, disciplining and punishing workers rather than giving free scope to their political potential. In a letter to Grace Lee written from Reno, Nevada as he was tackling Notes on Dialectics, James alludes to what he describes as the unnatural separation between political parties and labour unions in the US, and an emerging more advanced form of political organization that will integrate party politics and the labour movement. To illustrate his point he turns to the Caribbean: “in Trinidad & the W. I [West Indies] as a whole by the way, union leaders are political leaders & vice versa.” In Jamaica’s case this is problematically personalized around the charismatic character of Alexander Bustamante, first Prime Minister of an independent Jamaica. It did not represent the content of the mass political party that James had envisioned, but it did approximate it in form insofar as labour and the party were conjoined. In this sense the West Indian labour movement helped to crystalize a new conception of socialism in James’mind.

James’ Cricketing Philosophy

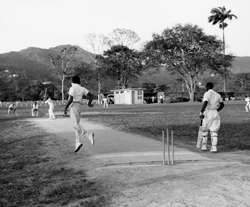

Lendl Simmons batting for the West Indies in 2009

Lendl Simmons © Adocentyn CC 3.0 Licence 2009

Notes on Dialectics is rich in drama: as he ventures into Hegel’s Doctrine of Being in Hegel’s Logic, James writes, “You know, as I propose to myself to begin the actual Logic, I feel a slight chill.” But it is Beyond a Boundary (1963) for which James reserves some of his most creative writing, arguing as he does that cricket is in-and-of-itself an artform.

Beyond a Boundary has been described as one of the greatest books ever written about sport, and the best book about the quintessentially English game of cricket. What makes it such a masterpiece is rooted in the Kiplingesque question James poses in the Preface: “ What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?” In this spirit, the book’s analysis extends well beyond the confines of the game: Beyond a Boundary is a book of aesthetics, ethics, and politics, neatly wrapped in James’ semi-autobiographical philosophy of sport.

His central argument is that “Cricket is first and foremost a dramatic spectacle. It belongs with theatre, ballet, opera, and dance.” While this is a characteristic that cricket shares with other sports, the ‘‘quality of drama is more specific’’ to cricket because it “is so organized that at all times it is compelled to reproduce the central action which characterizes all good drama from the days of the Greeks to our own: two individuals are pitted against each other in a conflict that is strictly personal but no less strictly representative of a social group. One individual batsman faces one individual bowler. But each represents his side. The personal achievement may be of the utmost competence or brilliance. The ultimate value is whether it assists the side to victory or staves off defeat.” For James, “The dramatist, the novelist, the choreographer, must strive to make his individual character symbolical of a larger whole. He may or may not succeed” but the “batsman facing the ball does not merely represent his side. For that moment, to all intents and purposes, he is his side.”

All of this is part of a “fundamental relationship of the One and the Many, Individual and Social, Individual and Universal, leader and followers, representative and ranks, the part and the whole… Thus the game is founded upon a dramatic, a human, relation which is universally recognized as the most objectively pervasive and psychologically stimulating in life and therefore in that artificial representation of it which is drama.” The game is characterized by ritual, routine, and regularity. Each bowling or batting episode adds to the dramatic tension by way of “immense possibility of expectation and realization.” Only baseball, is James’s view, approximates cricket in this regard, but the structure of cricket ensures a level of spectacle that (with the exception of international cricket, with all of its nationalist implications) is more important than the final score.

A game of cricket in Trinidad in 1960

James pays careful attention to the aesthetic of the bat stroke, and in keeping with his preoccupation with the creative capacity of the dispossessed, recalls his childhood memories of one player in particular who embodied James’ representation of sport as art, Matthew Bondman. As James recalls, “When I tired of playing in the yard I perched myself on the chair by the window. I doubt for some years I knew what I was looking at in detail. But this watching from the window shaped one of my strongest early impressions of personality in society. His name was Matthew Bondman and he lived next door to us.”

For James, Bondman is a quintessential example of the ‘barefoot man’ – a representative figure of the Caribbean underclass – perpetually unemployed, dirty, and not averse to using profane language. According to deeply-entrenched codes of respectability, in terms of Trinidad’s inherited Victorian-Edwardian manners and mores Bondman could only be perceived as a disreputable character, an outsider. Sylvia Wynter has argued that Bondman represents the West Indies’ equivalent of peasants consigned to hard labour in Stalin’s Gulag Archipelago, or the dispossessed in America’s inner cities, and, we might add, prisons. But this depiction of Bondman is outshone by another memory etched in James’ mind: “For a ne’er-do-well, in fact vicious character, as he was, Matthew had one saving grace – Matthew could bat. More than that, Matthew, so crude and vulgar in every aspect of his life, with a bat in his hand was all grace and style. When he practiced on an afternoon with the local club people stayed to watch and walked away when he was finished. He had one particular stroke that he played by going down low on one knee… whenever Matthew sank down and made it, a long, low ‘Ah!’ came from many spectators, and my own little soul thrilled with recognition and delight.” In James’ eyes, Bondman, bat in hand, is a fine artist and, with perhaps the exception of his characterization of the English cricketing legend W.G. Grace, his vivid depiction of Bondman is unsurpassed. Bondman is the batsman par excellence, who embodies James’ persistent point: so-called ‘ordinary people’, society’s dispossessed, possess the creative capacity to achieve the extraordinary. It is to James’ infinite credit, consistent with his preoccupation with the dispossessed, that he rescued the otherwise discarded Bondman, and the Bondmans of the world, from history’s dustbin.

James was a consummate polymath who made unique intellectual contributions in the areas of sport, political philosophy, history, literature, literary criticism and Marxist theory. He spent his waning years in Brixton, London. He died in May 1989, only months before the collapse of the Eastern Bloc – events that, in many ways, his critique of Soviet totalitarianism anticipated. He was buried in his native Trinidad.

© David Austin 2022

David Austin teaches in the Humanities, Philosophy and Religion Department at John Abbott College, and at the Institute for the Study of Canada, McGill University, Montreal.