Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Kierkegaard and the Question Concerning Technology by Christopher Barnett

Michael Strawser questions Kierkegaard about technology.

What does the father of existentialism have to teach us about how to think about Google? How should we authentically view the freedom of the press and the problem of fake news? How does one meaningfully relate to existence in the age of information? Christopher Barnett provides answers to these and many other intriguing questions about how we should consider our relationship to technology in light of the writings of Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855). His study is clear, engaging, and timely, and demonstrates not only a firm command of Kierkegaard’s work in its original Danish, but also deep knowledge of the related philosophical and theological traditions.

The tradition particularily relevant to this work is of course the philosophy of technology. Barnett opens with an overview of it, and highlights an important distinction between an ‘engineering philosophy of technology’ and a ‘humanities philosophy of technology’. The latter involves the attempt to reflect critically on the effects of technology on human existence. The central purpose of Barnett’s text is an exploration of the relationship between Kierkegaard’s thought and this human question of technology.

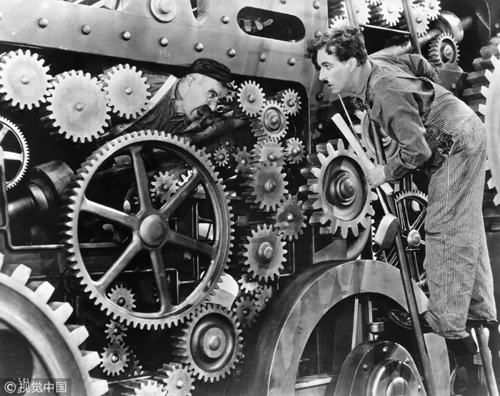

Image from Modern Times © United Artists 1936

Barnett recognises that Kierkegaard is not a philosopher of technology in any meaningful sense, and rarely used the term ‘technology’ in his writings. Nevertheless, Kierkegaard was acutely aware of the rise of the modern, secular world with its various new technologies, such as steam locomotives, the electric telegraph and high-capacity printing presses. His call for God-fearing reflection anticipates Heidegger’s response of ‘meditative thinking’ to the question of technology. It is Kierkegaard’s call to reflection regarding our relationship to technology that is of ultimate value in this study.

During his opening sketch of a general history of technology, Barnett writes that “Kierkegaard was principally concerned with informational technology or, as he preferred, ‘the press’” (p.2), and that “Kierkegaard’s insights regarding the press of his day have remained relevant in the twenty-first century and indeed, may even appear prophetic” (p.11). The focus of Chapter Two is ‘Technology in Golden Age Denmark’. Here Barnett describes the technological developments that Kierkegaard himself experienced, including advances in transportation, industrialization and publishing. He sets the stage for Kierkegaard’s entry into the debate on the freedom of the press by explaining historical events such as ‘the Freedom of the Press Petition’ of the 1830s, and cites research to show that “as late as 1842, twenty-two of the country’s twenty-four daily newspapers were subjected to censorship” (p.21). The historical ground covered in these first two chapters sets the stage for a closer examination of ‘Kierkegaard and the Rise of Technological Culture’ (Ch. 3), and ‘Kierkegaard’s Analysis of Information Technology’ (Ch. 4), while also demonstrating that “Kierkegaard’s sociohistorical location is by no means qualitatively different than our own” (p.27). In other words, the questions that troubled this Great Dane are ones that dog our own world too.

Barnett carefully explains the Danish terms Kierkegaard uses to question technology in his books, such as ‘discovery’ (Opdagelse). He also explains Kierkegaard’s reflections on the growth of the ‘bourgeois, busy, and crowded’ city. But as I said, most important are Kierkegaard’s views of the press. In an early student writing, Kierkegaard describes the press as an “unorthodox and unauthorized source of political power”, while in a later writing he laments “the noise of the world”, since “the spiritual life suffers in such a context” (p.36). The end of absolute monarchy and rise of liberalism in Denmark during Kierkegaard’s lifetime made him worry that truth (especially Christian truth) would be identified with the vox populi (p.40). Barnett also reveals how for Kierkegaard the scientific worldview is ultimately an aesthetic worldview. However valuable, it cannot “guide one through the deeply personal art of living well” (p.61).

Chapter Four includes a much closer look at the texts in which Kierkegaard discusses the press, from lesser-known early polemical writings that include a critique of journalism, to his later book A Literary Review (1846). Barnett argues that Kierkegaard’s worries about the media “persist to the present day, when people often struggle to distinguish between ‘real’ and ‘fake’ news” (p.69) – but he also shows that this concern didn’t lead to Kierkegaard supporting absolute control of the media by the state. Some of Kierkegaard’s worries involved depersonalization and reduced individual responsibility, leading to moral indifference and ‘levelling’. Yet ironically, Kierkegaard would later use the press in his attacks upon the Danish State Church. This could perhaps provide an opening for considering some of the benefits of information technology, although Barnett follows Kierkegaard in focusing on a negative critique of it. This continues in Chapter Five, where an application of Kierkegaard’s thought to our contemporary situation explores the perils of Google.

According to Barnett, “Hegel and Google stand in an analogous relation to one another: both promote the systematic collection and distribution of knowledge at the expense of human flourishing” (p.97). Kierkegaard’s criticisms of Hegel’s philosophical system are well known, and Barnett suggests that they indirectly call into question the desirability of the internet, raising concerns about dangers such as the loss of our humanity brought about by equating “the accumulation of knowledge with human well-being” (p.102). After all, it is possible to have too much information, and Google “does not just deliver information but also shapes the way persons relate to it” (p.105). Kierkegaard’s remedy for the corruption inherent in the systematic collection of information is Betragtning or ‘contemplation’, which Barnett suggests is a kind of therapy that “centers the existing person and, in turn, prepares the way for an earnest engagement with the whole of reality” (p.112).

Barnett is surely right that in the age of information we are easily distracted from contemplative thought. But considering recent events such as the Black Lives Matters and Me Too movements, one wonders if there is not also some good that has come about from our use of information technology. I’m particularly thinking of the concept of equality, which is central to Kierkegaard’s understanding of the love of the neighbor developed in his Works of Love (1847), and which has also been advanced by people today with the massive help of the internet and social media. Could applying Kierkegaard’s thinking on this lead us to a more positive appraisal of the new media? I raise this question in the spirit of Barnett’s study, and in particular his humble conclusion that this “project is fundamentally a point of departure [that] opens up possibilities” (p.158), in order to suggest that we continue to read Kierkegaard with an eye towards the question of technology, both negative and positive. Thanks to Barnett’s insightful study we are in a much better position to continue this work.

© Prof. Michael Strawser 2022

Michael Strawser is Chair and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Central Florida. He is the author of Both/And: Reading Kierkegaard from Irony to Edification (Fordham University Press) and Kierkegaard and the Philosophy of Love (Lexington Books).

• Kierkegaard and the Question Concerning Technology, Christopher B. Barnett, Bloomsbury, 2019, $35.96 pb, 256 pages, ISBN: 9781501378348