Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Political Philosophy

Revolt & Complacency

Stefan Catana on three revolutionary thinkers and their ideas for creating progress in politics.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw the birth of modernity, as Enlightenment ideas about science, reason and progress started permeating the intellectual circles of the Western world. Accompanying this, the very idea of ‘modern’ became identified with progress towards improvement and innovation. History was the march of civilizations and peoples in the direction of something better, something to look forward to which would bring more peace and move away from war and desolation. But such hopes were eradicated as the twentieth century took these ideals and one by one rendered them baseless. World wars, fascism, communist authoritarianism, and an overall wave of illiberalism, became the stark opponents of Enlightenment ideals. This encouraged a widespread perception that the ideals themselves were but an illusory dream. According to its new opponents, the Enlightenment was vague, had limited practical applications, wrongfully idealized human nature (and implicitly, human history) and disregarded the many differences among the myriad of cultures and lived experiences in pluralistic societies. Reason and progress were, apparently, never really true.

Thus the first half of the twentieth century drastically altered what was to come afterwards. Today, it seems that demagoguery, false idols, and illiberal populism have risen from their slumbers, forcing us once again to ask: are we really enlightened, or at least on our way to a better world, or are we doomed to repeat the calamities of the previous century? And what are we as individuals in relation to the state – especially when the state and those around us constantly seem to let us down? Three highly influential thinkers with three very different standpoints can help us better understand our times, and provide intellectual tools to aid us in fighting our contemporary demons.

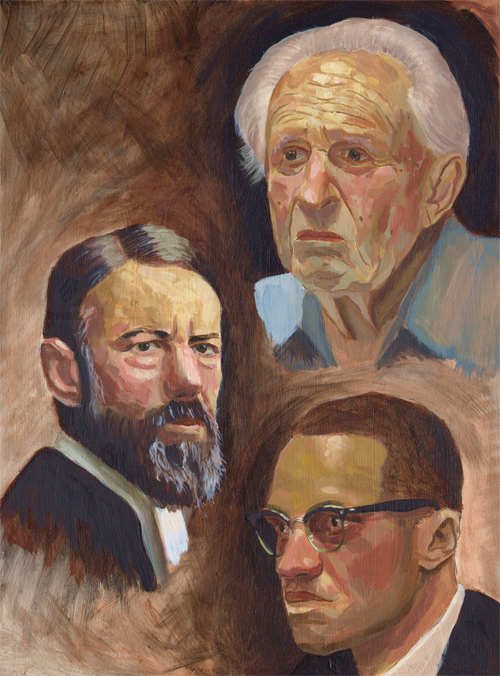

Marcuse, Weber and Malcolm X by Darren McAndrew, 2022

Max Weber

In 1919, as Europe lay in ruins, Max Weber (1864-1920) wrote an essay called Politics as a Vocation which reflects on the origins of the state. What makes it a state in the first place? How it is able to persist over time? He reaches the conclusion that what allows a state to exist is power, the ultimate instrument to ensure stability and order, or ‘keep things in place’. Not just any type of order, either, but one which does not allow itself to descend down the path of tyranny of the majority, as it did during the 1789 Revolution in France, which overthrew the monarchy only to pave the way for the Terror of the guillotine. Weber claims that a state is a “human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (p.1). The state is the sole authority which can enforce rules through legitimate means of force, and the sole entity which can justifiably exert control over the people who reside within its territory. Politics becomes essentially about having the means to get a share of that power, increase it, or distribute it to the population or certain groups of the population.

Weber says that to preserve its legitimacy, the state justifies itself in three main ways: (1) The ‘eternal yesterday’, which is the authority embedded in custom, culture, and tradition; (2) A charismatic leader who is able to garner the support of big crowds through his or her ‘charming’ personality; and (3) It upholds the legal system, with its myriad rules, which control day to day life.

For Weber this array of ideas has some ominous repercussions in the modern context. On the one hand, capitalism has been able to absorb some of the tenets of the Enlightenment to develop an economic system that has brought tremendous benefits by vastly increasing the resources available to both consumers and producers, lowering prices, increasing interdependence between states and nations, and facilitating a liberal order responsible for maintaining security and peace. It has raised millions of people from abject poverty, led to technological developments that play an important part in everyone’s daily lives, and has aided the transition from feudal, monarchical, and authoritarian regimes to ones grounded in the ideas of liberal democracy. But Weber also describes how one of the by-products of this process has been the emergence of a highly bureaucratic system of agencies and agents who live for and off politics, running a hierarchical establishment which creates laws and policies impacting individuals all the time. However, as a result of this bureaucratic situation emerging, we can arrive at a point where we believe we’re getting progress and more freedom, without necessarily questioning how, or even if, we get progress and more freedom. The possible bad consequences of this attitude is the ‘crisis of the Enlightenment’ that Weber was afraid of. They include an increasing materialism/consumerism, and an unbalanced promoting of the individual over the collective good with the accompanying erosion of shared values. So how does one begin to bring about change in a situation where we already assume we’re getting increasing freedom?

Weber himself advocates a politics based on an ethics of responsibility, saying that those who treat politics as their vocation should choose to act cautiously rather than revolutionarily. This, he says, is the only way to deal well with the ugly realities of politics, an environment filled with disagreements, hate, and competition for power and prestige. Unfortunately, Weber thus seems to run into the same cul-de-sac as Immanuel Kant did with his pamphlet What is Enlightenment? (1784). Kant’s apparent paradox of ‘Think for yourself, but obey the state’ cannot lead to any progress in a situation where people do not have any power to change the status quo. Both Weber and Kant offer precautions against adopting an ethics of absolute ends (that is, of saying that the ends justifies the means, as the communists often did, for example). But how are regular people supposed to challenge authority if it becomes clear that demagogues or dilettantes are leading a state down a dangerous path? If the middle road stops being an appealing option, does that mean that revolution is the only remaining choice?

Malcolm X

In his 1964 book The Ballot or the Bullet, Malcolm X issued a powerful message to black Americans by advocating what he called ‘black nationalism’. For him the term encapsulates black people’s means of self-determination. It refers to people making their own political decisions for their communities. It also implies, for instance, the right of black business owners to retain the rights to their businesses without being bought out by more powerful white companies or being forced to move out due to white businesses moving in.

Malcolm X offers a scathing critique that’s relevant to everybody. He believes that a predatory political/economic system has historically acted reprehensibly towards black people (and who could sensibly disagree?). He further points out that politicians suffer from execrable and blatant hypocrisy, as they only pretend to care about the plight of the black community when they seek their votes to get reelected, but at the end of the day they’re still part of an elite group that looks to protect its own interests without really caring about the people they represent. He argues that black people have for too long allowed themselves to be tricked by people who just want their vote; and, moreover, that participating in a rigged game of politics that is systematically designed to work against them helps inequality and racism to persist.

It is critical to note that Malcolm X not only advocates a radical change in politics, but also places a strong emphasis on individualism. He’s proposing a ‘self-help program’ and a ‘do-it-yourself philosophy’ (p.5) which stresses the importance of people being able to think for themselves and make intelligent decisions without being pressured by external forces. This is along the line of Enlightenment thought, and agrees with Kant in asking people to think for themselves. The difference is that Malcolm X does not share Kant’s respect for authority. He knows that the particular authority with which he’s dealing has been falsely saying that it’s giving black people freedom, equality, and opportunities, while those are just make-believes, part of an act put up by the politicians to retain their power. Malcolm X says that at the end of the day it’s voters who choose who makes the decisions for them, so therefore those same politicians depend on the people to vote for them – they’re utterly powerless without them. Once black people themselves recognize this, they will understand how to create the window for changes to happen. They will understand that everything is about power: about amassing political power and retaining it as much as possible. An awakening of the masses is the only thing which can change their situation, by their being politically active, by registering to vote and using that vote; and if the ballot does not work, he says, then perhaps the only solution that remains is the revolutionary bullet…

His message remains strong today, but now speaks on a more universal level.

Herbert Marcuse

The German critical theorist Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979) agrees with Malcolm X that history has always been written by the victors, and that many political concepts, rather than being objectively true, are socially constructed by those in power.

For example, Marcuse rejects the idealised Western concept of progress. Instead, he believes that through its various processes of mass production and mechanization, modern industrial society has had a very dangerous impact on the individual. He begins his book One-Dimensional Man (1964) by arguing that there is a great ‘democratic unfreedom’; that contemporary industrial society is totalitarian by having suppressed all true forms of freedom. There is a distinction between true and false psychological/emotional needs, and the former are being suffocated and slowly exterminated at the expense of the latter.

Unfortunately, keeping people in their place by not freeing them to pursue that which they find meaningful renders them unable to really think for themselves. In particular, they’re unable to realize the necessity to detach themselves from a repressive culture which promotes nothing but conformity and the status quo, where the people think they are free despite, for instance, the fact that they have little say in how the policies and laws enacted by those in power affect them. So effective is this system that often the individual does not even think to challenge its authority. The concept of revolt – of even imagining a world where he or she is not dependent on the system and its authoritarian practices – simply does not exist for them. The mechanization of the outside world has been replicated inside the individual’s mind, making them a cog in the industrial machine. It’s Weber’s worst nightmare come to life:

“We are again confronted with one of the most vexing aspects of advanced industrial civilization: the rational character of its irrationality. Its productivity and efficiency, its capacity to increase and spread comforts, to turn waste into need, and destruction into construction, the extent to which this civilization transforms the object world into an extension of man’s mind and body, makes the very notion of alienation questionable. The people recognize themselves in their commodities; they find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment. The very mechanism which ties the individual to his society has changed, and social control is anchored in the new needs which it has produced.”

(One-Dimensional Man, p.9).

This is, quite frankly, terrifying; yet also very familiar.

Marcuse claims that as industrial society becomes more modern and advanced, this also strengthens the perception that it is the embodiment of reason itself, and thus needs to continue unchallenged. Sadly, people just accept this because the sheer ubiquity of technology has led us to believe that all of it is necessary. Eventually there will be no one left to challenge the industrial-technological system, and the entirety of humanity will be left in a state of paralysis, of unconscious inertia, in an unawareness that has grown over the course of the last few centuries. As the mass production of information and material goods that we now consider essential to our daily lives – including our phones, tablets, and laptops – reaches a global scale, and when we all believe that the purpose of life is to work, to make money, then the indoctrination of the masses will be complete. When the commodification of everything becomes a way of life, one-dimensionality reigns. This is how the system ends up controlling the people.

Through arguing that everything it tells you is true and represents Reason, the system also acquires another weapon. Every idea which cannot fit the contemporary standards – indeed everything which is different from what’s normally expected – is ostracized on the basis of being otherworldly, arcane, strange, or evil. The system can even perpetuate its ideals through categorizing alternative ways of thinking as potentially bringing about the end of the world if they’re allowed to exist. The Cold War provides a prime illustration of such panic-mongering.

These are the reasons for Marcuse’s blistering attack on positivism, the Enlightenment, and even rationality itself. His critique of society is in line with Malcolm X’s in that they both argue that the socially-constructed nature of accepted political truth has always been used to keep both the masses and minority groups within the population down, justifying their oppression and making them inferior. Marcuse’s critique is also reminiscent of Weber’s, in that technological innovation and mass production in a capitalist system, while providing a sense of liberty, freedom, and increased wealth are but novel forms of domination: “Free election of masters does not abolish the masters of the slaves” he writes (p.7). Political relationships are based on one person exercising power over the other. This does not change in modern industrial society; it is even exacerbated by technology.

How does Marcuse propose we fix this situation of control? His solution involves a distancing from the systematic oppression in industrial societies through negating the power dynamics that have been forced upon people by those in power. It is an attempt to understand that what we’re being sold, both in terms of goods and ideologies, is fabricated. First, Marcuse argues that individuals need to adopt his so-called ‘great refusal’ – a rejection of commodity-based living in favour of artistic self-expression. Here he lays the groundwork for a future movement that rejects the consumerist nature of modern life and instead embraces a new sensibility that places importance on the things that we really value as individuals, and not what people on the TV or in advertisements tell us to value. It is a replacement of a capitalist subjectivity (touted by industrial society as ‘objectivity’ and ‘progress’) with one’s own subjective values. If only we can connect with those inner values, we will understand that the things that we truly want are different from the things we think we want. This realization would lead to a better, cleaner, more equal world, where profit is not prioritized over the well-being of people, and where those who are now neglected or oppressed would be integrated into society.

Paths To Revolutions

But how are we supposed to find the path to our own subjectivity if we are already cogs in the machine? Maybe Dostoevsky was right in saying that people prefer to be controlled, if it means they can enjoy the daily comforts of life.

How do we reconcile the revolutionary spirit, which is brutal and violent, with the ideals of the monotonous, unfulfilling, yet reassuring life that modern society offers? Here is where I believe the three authors converge. They all address the reader as the personally-realised individual, not as the socially created one. They’re looking you in the eyes and asking: What do you want ? What is the impact you want to make in this world, and how will you do it? For instance, will it be by adopting an ‘ethics of responsibility’ which balances a revolutionary spirit with the caution that one maintains when dealing with politics and power? Or will it rather be through the ‘ethics of absolute ends’, which does not take into consideration the way something is achieved, but only cares that the goal is reached – and if that requires thousands to die, then so be it.

How to best implement necessary changes in society is a difficult, and possibly impossible, question. Weber might prefer the first option – cautious development – while Malcolm X and Marcuse would possibly go for the second: revolution ‘by all means necessary’. Nonetheless, one conclusion I have come to, is that the first step must take place within ourselves. Before we decide upon the ethics we must follow, it is better to understand our own condition and our own purpose in this highly complex world.

The spirit of revolution can spread very easily; but it can just as easily descend into chaos and ravage an entire society. Yet at the same time, complacency makes one oblivious to existing corruption and inequality. By being a mere passenger, one allows the trains of unfairness and immorality to continue on smooth rails. Change is as timely as it is inevitable – yet before we rush to make decisions about the future shape of the world, it is better to detach ourselves from the social dynamics which place us in limbo in a cycle of political insensibility. First understanding who we are can make it easier for us to understand who we must be, and can allow us to engage knowledgeably in ardent debates about the social dynamics that constrain us. Perhaps only then will we be able to master modern society and our role in it.

© Stefan Catana 2022

Stefan Catana is a recent graduate of the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles.