Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Kindly with Kant

Seán Moran imagines Immanuel as an inn-keeper.

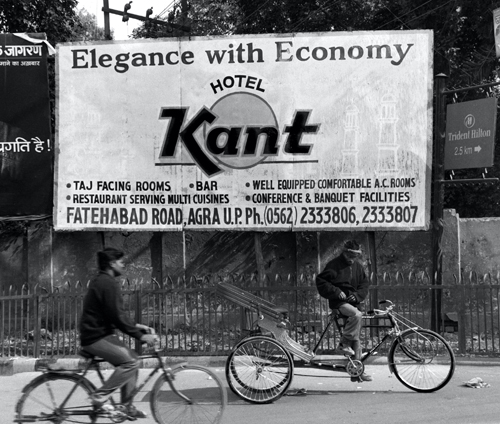

Yes, it is real. Kant’s hotel is located near the Taj Mahal in Agra, India. Immanuel Kant himself never lived anywhere apart from his home-town of Königsberg, Prussia (now called Kaliningrad, in Russia), so this Indian hotel has nothing to do with him. But when I took the photograph, it started me thinking about what a hotel run on Kantian principles would be like.

Photo © Seán Moran 2022

If he were involved, we’d expect everything to run punctually, in stereotypically Prussian style. Indeed, Kant’s routine was so predictable that the locals could tell the time by when he passed by on his daily walk (they reportedly called him ‘the Königsberg clock’). And as guests in his hotel, we would also be looked after very nicely. One of Kant’s core ethical rules was that we should never treat other human beings just as means to our own ends. So the hotel staff would be required to treat residents as autonomous individuals whose dignity ought to be respected at all times, not merely as anonymous income streams. People staying in the hotel would be honoured guests to be welcomed and cosseted rather than faceless nobodies to be barely tolerated in the interests of profit. In fact, it seems that any good hotel would treat us in this Kantian way.

But what if it doesn’t live up to our expectations? When things go wrong, how can we encourage good customer service from a hotel while still keeping our own actions in line with Kant’s ethical imperatives?

The direct approach would be to summon the manager, explain our dissatisfaction, and state bluntly what actions we expect them to take. This line of attack has the merit of simplicity, but it marks us out as a ‘Karen’ or a ‘Kevin’ – an entitled first-world folk-villain, increasingly the subject of internet scorn (apologies to Philosophy Now readers called Karen or Kevin). And although our assertive actions may well lead to surface compliance by staff, they could also breed resentment, even sabotage, given half a chance. Can you guarantee that no waiter has ever spat in the soup of an obnoxious customer? Or that no receptionist has ever allocated the worst room in the hotel to an impolite guest?

If we are to be consistently Kantian in our own behaviour, and not just demanding of Kantian behaviour towards us, the solution is straightforward: we ought to treat the hotel staff as fellow human beings. For instance, we shouldn’t demand service in a brisk (or brusque) way, but should instead cultivate warm, authentic human interactions with staff. If we don’t want to be treated as faceless customers, we must in turn pay attention to the faces of the service workers – and to their name-badges. We look them in the eye, address them by name in a friendly manner, and establish an equal connection between human beings rather than a hierarchical relationship between a haughty customer and a subservient worker. This is pragmatically a good idea, for it increases our chances of decent service; but more significantly, it recognises the fundamental humanity of the hotel staff. On a Kantian analysis, it is this humane element that has the moral clout, for to be warm to staff only for strategic reasons is again to treat them merely as means to an end.

Let me give an example. I once stayed in a down-market hotel near the Périphérique in Paris. It was out of season, so I knew that my street performances on the flute wouldn’t bring in much money – hence my need to economise. Having paid for ‘room only’, I wasn’t even entitled to breakfast.

Cheap as it was, I definitely won’t be returning to that hotel. I hadn’t noticed the bed-bugs when I settled down to sleep, but I certainly felt their presence when I woke up in the night, itching, and covered in red marks.

My problem was how to bring this incident to the hotel’s notice, and ideally receive some sort of fair recompense, without turning into a Kevin. So in the morning I emptied out the clear polythene bag that had carried my toiletries on the flight to Paris and captured a few choice specimens of Cimex lectularius. This wasn’t hard to do, since they were bloated after a decent meal, having feasted on me through the night. I took them down to Reception and waited until there were no other guests about. “ Bonjour, Monsieur,” I said. I passed my groggy specimens to the receptionist and announced: “The bed-bugs have had their free breakfast, so…” After a moment’s thought, he figured out the unspoken implication, and smilingly offered me breakfast by way of apology, “ avec les compliments de la maison.”

I could have been nasty about the incident, and demanded more, perhaps even insisting on a full refund, but I saw the funny side of things, and the solution worked for me on a human level. Bed bugs are not dangerous, after all, just an itchy nuisance. And it allowed me to give a new punchline to the old philosopher’s joke (which needs to be said outloud):

Philosopher: Have you read Marx?

Street Philosopher: Yes, it’s the bed-bugs.

Sublime Phenomena

Although he would have missed Königsberg, Kant would surely have enjoyed seeing the Taj Mahal. Except that he wouldn’t be seeing the real Taj Mahal, only its appearance. Kant argued that behind the visible world – behind ‘things-as-they-seem-to-be’ – lies a realm of ‘things-in-themselves’ (Dinge-an-sich in the German). Our senses only allow us to access the ‘phenomenal’ world – the world of appearances, or ‘phenomena’ in Greek – and not the real, ‘noumenal’ world that actually underlies it. So, the noumenal Taj Mahal (the Taj-an-Sich, as we might say) is forever out of reach. Even so, the Taj Mahal as it appears is worth seeing. We might say it’s phenomenal!

The back-story only adds to its appeal. The Moghul emperor Shah Jahan had it built around 1648 as a mausoleum for his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal – it’s a monument to his undying love for her. And as well as the official romantic story, there’s the national symbol story, and the wealth-generation, job-creation stories, although the ordinary resident of Agra doesn’t seem to have benefited from the gate receipts at the Taj – unless those folks washing clothes on a rock in the Jamuna river are waiting for their state-of-the-art washing machines to be repaired. There will also be your own personal story the next time you visit it.

The mere appearance of this marvellous building, together with our knowledge of what it represents, is enough to awaken both sublime and beautiful feelings in the sensitive soul. Kant himself classifies agreeable aesthetic experiences in exactly this way in his paper ‘Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime’ (1764). He further subdivides ‘the sublime’ into three categories: “I will call the first the terrifying sublime, the second the noble, and the third the magnificent.” On this classification, the Taj Mahal surely belongs under the heading ‘magnificent’.

Robert Hicks helpfully links the Taj Mahal with Kant’s classification:

“To appreciate what Kant may have been struggling with in his attempt to explain our experience of great art, we need only contemplate the blend of sublime and beautiful feelings aroused by works of artistic genius such as… the Taj Mahal: we respect such works, we find our imaginations staggered by them, and yet we love them with a beautifully familiar affection.”

(The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1995)

I know what he means.

We should not be too precious about such elevated feelings, though. If you visit it, you will only be able to stand and stare and drink in the magnificence of the Taj for a few minutes before an enterprising local, in the hope of a tip, will start advising you about good locations to take photos, or invite you to sit on the ‘Lady Di Bench’.

The Taj Mahal is such a familiar icon that I felt hungry just by looking at it. This is a clear case of Pavlovian conditioning, since back home in Ireland I’ve often dined in Indian restaurants with a picture of the Taj Mahal on the wall. This psychological association between the Taj and the imminent arrival of spicy food is triggered even more strongly by being in the presence of the actual (though still only phenomenal) masterpiece than by kitschy images in restaurants. However, perhaps these interpretations of the Taj Mahal enable us to triangulate towards the real building – the Taj-an-Sich.

What of Kant’s own writings as works of art? On his own criteria they fall flat: even his biggest fans would not typically describe the Critique of Pure Reason as ‘beautiful’ or ‘sublime’. (When I was doing my Master’s in philosophy at Queen’s, my tutor tried to put me off studying the Critique: “There’s no such word as Kant”, he said in his Belfast accent. I’m glad that I politely ignored that particular piece of advice.) There is however a work of great power and beauty hiding behind Kant’s turgid prose and difficult, abstract ideas. It’s a pity that Kant didn’t allow his warm personality to shine through in his writing. He could be a sociable man, and “his lecturing style, which differed markedly from that of his books, was humorous and vivid, enlivened by many examples” (Britannica). Vividness, examples of what he’s writing about, and humour, are all missing from his Critique. This is why it is such hard-going.

And what of the Hotel Kant, Agra? Alas, I stayed in a different hotel, so I cannot judge it either as the phenomenon or as the thing-in-itself. As long as the ‘Information for Guests’ is free of Kantian prose, and, more importantly, the beds are free of Cimex lectularius, it might be worth a stay. Tell them that Kant sent you, and you were hoping to experience ‘the moral law within’ their staff, and the ‘starry heavens above’ the Taj Mahal.

© Dr Seán Moran 2022

Seán Moran teaches grad students at a new Irish university called the SETU. He is also professor of philosophy at one of the oldest universities in the Punjab.