Your complimentary articles

You’ve read three of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Metaphysical Animals by Clare Mac Cumhaill & Rachael Wiseman and The Women Are Up to Something by Benjamin Lipscomb

Katie Barron look at two books on four famous female philosophers and friends.

Two books have recently been published within months of each other exploring the lives of the same four female philosophers and making the same claim – that these four friends were the leaders in demolishing the logical positivism and moral relativism that dominated English-language philosophy in the mid-twentieth century.

The four young philosophers, Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch, met as undergraduates in Oxford during the Second World War and became close friends. Women had only recently been allowed to take degrees at Oxford. Suddenly, all the young men were away fighting, and the women could spread their wings.

Elizabeth Anscombe and Philippa Foot both became philosophy tutors at Somerville College, Oxford. Anscombe wrote five books, including Intention (1957) – a key work for moral philosophers. She also translated Ludwig Wittgenstein’s works into English. Foot developed the now well-known ‘trolley’ thought experiments which still highlight moral dilemmas, and are also used in psychological experiments: A runaway trolley, or tram, is on a crash course to kill a dozen people working down the line on the track. You are standing by the points when you see what is about to happen. Should you pull the lever to divert the train onto another track, so that you willfully kill just one person working on the other line?

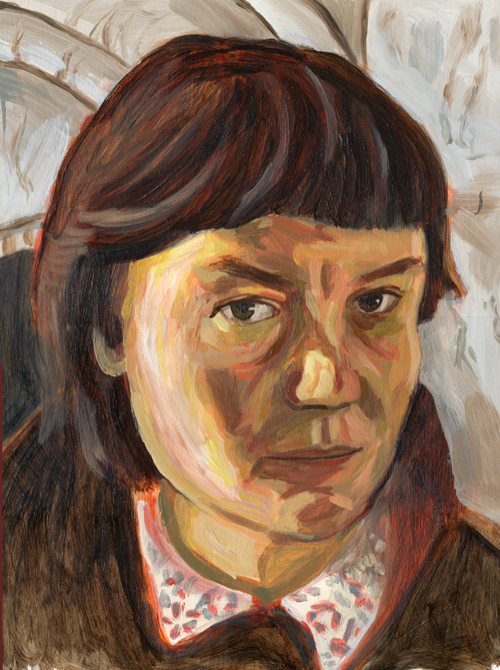

Iris Murdoch by Darren McAndrew

Iris Murdoch wrote loving letters to all three friends, and wrote much else on love, both in her novels and in her philosophy. In the years after the war, Murdoch was also a chief expounder of French existentialism to the Anglophone world. She had met Jean-Paul Sartre while doing relief work in continental Europe.

The fourth member of the group, Mary Midgley, became a philosophy professor in her thirties, but only started writing the eighteen books that made her so well-known in her fifties, when her children needed her less. She was a multi-disciplinary writer based in Newcastle, drawing on both philosophy and biology to explore human nature. In Beast and Man (1978) she deconstructed the myth of human ‘beastliness’. We are animals, and so, like animals: but animals are not all like each other, neither across nor within species.

Metaphysical Animals and The Women Are Up to Something are in a sense Midgley’s nineteenth and twentieth books. Metaphysical Animals starts with Midgley’s letter to the Guardian in November 2013, in which she described the war years in Oxford as ‘The Golden Age of Female Philosophy’ – a crucible of thought for her and her friends. In The Women Are Up to Something, Lipscomb highlights Midgley’s perception of gendered styles of thinking: women “are more conscious of the complexity of their subject and less powerful at abstracting.”

Was it feminine qualities, or just being outside the philosophy ‘boy’s club’ which enabled these four women to open up the subject in new directions? Through the influence of men such as AJ Ayer and JL Austin, philosophy had become both over-specialised and over-general – a caricature of philosophy that perhaps still abides today which can lead people to feel it has little use, either practical, psychological or spiritual.

The answer to the naturalists, the logical positivists, the moral relativists of their time, was to take them on on their own ground: language. Wittgenstein and Anscombe, then Anscombe with her friends, came up with concepts about language that have become part of our mental furniture now – such as that words are always spoken in a context, and that the context influences their meaning. To use the sort of mathematical-style equation which the Oxford logicians liked so much: Meaning = Text + Context. And it’s not only a question of saying. The same applies to seeing. I can see a bony man, or I can see a starving man, or I can see a moral outrage. Each time, I am seeing the same thing, but the context in which I see it affects what I see. Anscombe constructed a similar argument in her book Intention. A person pumping water is intending to fill a bucket: that same action may also have in it the intention of poisoning someone, if that’s the context.

More important than the answers these women gave to the moral and philosophical questions they were asking, which answers were always in a state of flux, was the ongoing debate – the grappling, the finding each others’ thoughts and trying to complete them, the observation of one’s own thinking and use of language. For Anscombe this activity tended in the same direction as religion, as “a feat of self-observation and self-transcendence.” All four were generous teachers, lavishing time and encouragement. All four put their ideals into action: Anscombe through her conversion to Catholicism, Foot with the charity Oxfam, Midgley with family life, Murdoch with her ideals of love.

Anscombe and the Christian theologian and Narnia novelist C.S. Lewis fought a verbal duel at the Socratic Club in Oxford in 1948 on the subject of miracles. They both believed in miracles, both being deeply religious; but Anscombe never looked for the easy path to resolve a question. She managed to show that Lewis had oversimplified the issue. Indeed, the debate seemed to have traumatised Lewis so much that he temporarily retreated out of philosophy into writing children’s books!

Young Elizabeth Anscombe

The argument at the Socratic Club had been about how to answer naturalists who believed that science could explain everything so that there was no need, or indeed room, for supernatural phenomena. Lewis claimed that naturalism was self-defeating, because if everything humans did had a biological cause then reasoning was also caused by biological processes, but reasoning couldn’t itself be justified if it was merely the result of random events. Why believe human reason if it’s just the result of random evolutionary processes, especially if the aim of these processes is survival rather than truth? Anscombe countered that there are non naturalist causes that are not supernatural and so, although she believes in miracles, Lewis has not proved the necessity of the supernatural just by reducing the naturalists ad absurdum. There are different kinds of causes, Anscombe said, trying not to be too acerbic: different answers to the question, ‘Why?’ There are biological reasons why a person thinks or says something (for example, chains of nerves and muscles firing in particular patterns), and there are linguistic reasons, to do with chains of argument, directions of conversation, and the common understandings of speaker and listener.

I wonder what happens if you try to give different types of explanation at once? For example, what if you want to explain how a philosopher arrives at an argument both through their reasoning and through their lived experience as a feeling organism in the world? How do you give an adequate account of a ‘metaphysical animal’? This is the narrative problem that Lipscomb, on the one hand, and Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman on the other, have faced in giving their accounts, both philosophical and historical, of how four women ‘brought philosophy back to life’ in the decades after the Second World War. Both books are immensely rewarding, but also challenging, because, as Lipscomb reminds us early on in his book, words tend to make pictures in our heads. While my brain is busy building up a picture of four young women studying in wartime Oxford, my brain is also tasked with picturing all the very different things that they were thinking about – which were not tied either to themselves or to their surroundings.

Lipscomb separates out thoughts and actions into sub-sections. He traces each woman’s life touchingly, from a family background of intense love (Murdoch) or lovelessness (Foot), through decades of work, to their most significant achievements, against a background that was unwelcoming both to their gender and to their passion to restore a moral philosophy that might be more than just ‘clever’ – to create a philosophy that might help and guide us now, as well as leaving us free to go on thinking about ethical issues in the future. His book also works as a very readable introduction to Western moral philosophy.

Mary Midgley

© Martin Midgley 2011

Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman’s narrative choices are much less conventional than Lipscomb’s. They dot about in time; they dive into philosophy halfway through a paragraph; they give potted histories of seemingly absolutely everyone the four women ever bumped into; they tell us about rationing and bombed tube stations, mouldy bathrooms, and ancient erudite refugee scholars. The four philosophers merge with each other and with their surroundings. Metaphysical Animals is a biography not of four individuals, but is genuinely a group biography. We emerge with a strong sense of what it was like in the 1940s and 1950s to be one of those women. We are partaking in their conversations and relationships; in their black-out commutes on the railway between Oxford and Cambridge; we are sitting on the floor with Murdoch and Foot, in leather armchairs with Foot and Anscombe, and in deckchairs with Anscombe and Wittgenstein (Wittgenstein chose sparse furnishings for his rooms in Cambridge).

I am both intrigued and uneasy at Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman’s choices. As philosophers, Anscombe, Foot, Midgley and Murdoch are not as well-known to the general reader as some of their male contemporaries. This is why both these books establishing their contribution and tracing their connections are so welcome, especially when they actually get on to how they defeated the moral relativism of Ayer, Austin, and Richard Hare. Yet to mix these women so entirely with each other, with their sexual relationships, and with the domestic aspects of their lives, and to call them affectionately throughout by their Christian names while maintaining the respectful distance of surnames for the male scholars, seems to collude with patriarchy. Surprising writing choices then from two female philosophers who have vowed to put these four thinkers on the map via their project ‘Women in Parenthesis’ (womeninparenthesis.co.uk). Their love lives, and their brushes with other, more famous people, were emphasised even more in the excerpts taken from Metaphysical Animals featured on BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week in February this year. In that serialisation, read by the period actress Fenella Woolgar, who stars in the tear-jerking historical drama Call the Midwife, their story became a comedy of manners.

© Katie Barron 2022

Katie Barron works with the agency Diversity and Ability to support neurodiverse university students in the UK. She is the author of Pilgrimage in Terror, an exploration of the tensions within pacifism.

• Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life, by Clare Mac Cumhaill & Rachael Wiseman. Chatto & Windus, 2022, £17 hb, 416 pages. ISBN: 978-1784743284

• The Women Are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics, by Benjamin J B Lipscomb. OUP USA, 2021, £20 hb, 344 pages. ISBN: 978-0197541074