Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering by Scott Samuelson

Doug Phillips arms us against the slings and arrows, as he tries to find a point to pointless suffering.

When indie band The Smiths were still together, and I, falling apart, was listening wistfully to their records, I remember always feeling run over by their first album’s last track, ‘Suffer Little Children’. A funeral march of mournful chords and lyrical melancholy, the song recounts the serial murders in the 1960s of five children in Manchester, some of whose bodies were found buried in the local moors. They had been sexually assaulted.

For many, any attempt to make sense of pointless suffering must first begin with the suffering of innocents. Scott Samuelson begins his own ruminations in Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering with his witnessing, as a young boy, a friend being struck and killed by a speeding car. “The suffering of children,” he writes, “sharply illustrates the gap between how the world is and how we think it should be” (p.1).

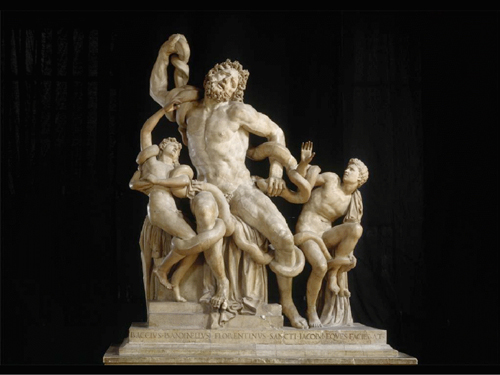

This divide between reality and desire is especially wide for those who must bear their own children’s suffering, as we see so poignantly in Michelangelo’s Pieta, but also terrifyingly in a figure Michelangelo helped to dig up: that of Laocoön and his two sons being tortured together. Laocoön (whose impassioned face appears on the cover of this book), along with his children, was set upon by sea serpents for having gotten his nose in the business of the gods. After warning his comrades about the ruse of the Trojan horse, he was condemned by Minerva to suffer terribly, for the crime of having acted virtuously. The famed ancient sculpture of this, found in 1506, gives exquisite, excruciating expression to the legend. Laocoön’s agony is akin to Christ’s, but he’s entirely without hope for redemption, salvation, reward, or justice. His suffering, it’s fair to say, is pointless. Like his innocent sons, Laocoön is a marbled flux of sinewy resolve and tortured resignation. The image is compelling, writes Samuelson, “because it crystallizes a fundamental, perhaps the fundamental, aspect of the human situation. The story it tells is about how suffering presents itself as pointless” (p.114). Do the right thing, do the wrong thing, it doesn’t much matter in the end: you and I will suffer all the same; and so too will our children.

Michelangelo’s Pieta

No Grief, No Good?

How, then, asks Samuelson, are we “to relate to this bitter fact of the universe?” (p.114). Given the inevitability of suffering, what, if anything, can we do about it? What should we do about it?

One thing’s for sure: we, like Lady Macbeth, can’t ever wash our hands clean of the pain. “For twenty centuries,” observed Albert Camus, “the sum total of evil has not diminished in the world” – which is to say, the damned spot of human evil won’t ever out, because it’s forever in. For example, the advent of mobile phones has greatly increased our access to information, but evidently at a high cost to our mental health. For many people, screen addiction means increased rates of anxiety, loneliness, and depression, never mind diminished attention spans infecting whole fidgeting generations. As Samuelson puts it, suffering “can never be eradicated, and when we do try to eradicate it, we generate whole new forms of evil” (p.221). Misery and pain get endlessly recirculated, exchanged, kicked down the road, or put off for a while, before boomeranging right back.

Some thinkers, such as Hegel, believe that no matter the sum of suffering, the good will always outweigh the bad, and that everything works out best in the end – a theory Schopenhauer thought easily testable by polling the respective feelings of two animals, one of which is eating the other. Regardless, we, like Laocoön, live in the gap between how things are and how we think they should be: in what the poet Keats, in an 1819 letter, calls ‘the Vale of Soul-Making’. Occasionally suicidal – and in any case condemned to an early, tubercular death – Keats is apparently desperate to convince himself of “how necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a soul. A Place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways!”

Samuelson agrees. Without such a proving ground as human life, wonders Samuelson, what opportunities would we have to realize our humanity? What need would we have for all those fields of inquiry and belief – science, technology, history, philosophy, poetry, art, religion –that enrich and give meaning to life? For Samuelson, as for Keats, “pointless suffering is where the journey of meaning-making begins” (p.4).

But make no mistake: such meaning-making comes with a cost. The Old Testament’s book of Ecclesiastes, which deals with human suffering, calculated the price of wisdom to be grief. And truth, insists the Greek tragic playwright Aeschylus, is something we must suffer into. To have it otherwise would be “a suicidal wish,” warns Samuelson: “No evil, no us” (p.105).

But whatever greater good or cosmic purpose we might divine or rationalize for our suffering, we, like Jake Barnes in Hemingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises (1926), still want to know how to live in it. “Maybe if you found out how to live in it,” says Barnes, “you learned from that what it was all about.”

This ultimately is Samuelson’s project. Nietzsche wrote “What really arouses indignation against suffering is not suffering as such but the senselessness of suffering” (The Genealogy of Morals, 1887)). He also believed “if we possess our why of life we can put up with almost any how” (Twilight of the Idols, 1889). Taking his cue from Nietzsche, Samuelson is also on a quest for meaning, for discovering what it’s all about : “this book is largely about how people have found a point in suffering: how artists have found in it the inspiration for our essential works of art, how spiritual leaders have found in it a road to God, how philosophers have found in it atonement with nature and training for our fundament virtues” (p.4).

Striking Attitudes to Suffering

Toward this goal of meaning-making, in the first half of his book Samuelson offers ‘Three Modern Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering’, with John Stuart Mill, Hannah Arendt, and Friedrich Nietzsche as his guides. In the second half, he puts forth ‘Four Perennial Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering’ by way of Job, Epictetus, Confucius, and (most fascinatingly to me) Sidney Bechet, a famed clarinetist who played and wrote the blues as passionately as anyone. Bechet is the expositor par excellence of what Samuelson calls the blues understanding of “confronting suffering, living in relation to it, doing battle against it, and ultimately coming to terms with it” (p.215). This understanding informs the whole of Samuelson’s study, from front cover to final page, but especially in those passages in which he draws upon his experiences of teaching philosophy to inmates at the Oakdale Prison in Iowa, many of whom were incarcerated for life.

After Covid, lockdown, and now with the threat of military escalation hanging over the world, we’re all in need of blues understanding, now as much as ever. Although Samuelson’s book went to press before Covid-19 reared its ugly head, his philosophical quest for how to live remains pressing in the age of plague, when suffering, like the falling snow at the close of Joyce’s short story ‘The Dead’ (1914) is ‘general all over’. Of course, suffering is and has always been general all over: it’s constitutive of our earthly condition, at least until further notice. But in cutting us off from easily procured entertainments and distractions (never mind from our work, our friends, our routines, and our routine busyness), the pandemic put us face-to-face with the point of our existence – or one might rather say, the pointlessness of our suffering. In so doing, Covid-19 confronts us with Schopenhauer’s sardonic conditional: “If the immediate and direct purpose of life is not suffering then our existence is the most ill-adapted to its purpose in the world” (On the Suffering of the World, 1850).

Rather like Freud, whose practice it was to help deeply miserable people readjust themselves into a life of ordinary unhappiness, Samuelson wants to help us rethink our understanding of suffering so that we not only become better adapted to its pointlessness, but perhaps even may overcome it. We might, for example, strive with Mill to alleviate all debilitating forms of pointless suffering as best we can, while at the same time recognizing, in Samuelson’s words, that a “genuinely human existence requires a structure of death, suffering, and freedom” (p.109). As Mill discovered for himself – he had a nervous breakdown at a young age – vulnerability, conflict, and struggle are necessary for achieving the ancient Greek ideal he prized above all, that of eudaimonia or self-flourishing. Nietzsche, whose own indebtedness to the ancient Greeks is well-known, also thought suffering necessary to all that’s good in life, whereas its avoidance is a far worse fate – in Dostoevsky’s term, making one unworthy of suffering. It means dooming oneself to mediocrity, to atrophying into Nietzsche’s ‘last man’, who, in making himself comfortable demands nothing higher of himself, ever. To circumvent such a fate, “Nietzsche encourages us not to tranquilize ourselves,” says Samuelson, “but to embrace life to the fullest, which means to embrace the suffering that’s inseparable from life” (p.59).

Laocoön & sons at the pet shop

Pushing the Poles Together

To return once more to the duel between Laocoön and the sea serpents: this figure of pointless suffering, claims Samuelson, embodies our own existential condition, while giving us an example of how we might live in it. Like Laocoön, we have a paradoxical obligation when it comes to our own duels in life.

Samuelson brings this paradox to the fore with his book’s epigraph, which is a passage taken from James Baldwin’s closing remarks in his book Notes of a Native Son (1955). Channeling Keats’ negative capability, Baldwin makes the case that if we’re not to fall into despair then we must hold two contradictory ideas in our head at once. The first is to accept “life as it is, and men as they are”, including that “injustice is commonplace.” At the same time, insists Baldwin, “one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength.”

Throughout his book Samuelson attends to the same basic paradox: we must strive to fix what afflicts us with all our energy and ingenuity, while at the same time facing what we cannot completely remedy, ameliorate, eradicate, or forget suffering. Consider for example the intractable fact of death; in Larkin’s words, the “sure extinction” which “we travel to / And shall be lost in always” (Abade, 1977). For medical doctors, death is the enemy they’ve sworn to fight, but death – their own, as well as their patients’ – is something they, like we, must also accept. And while we often try to forget what we can’t fix by taking refuge in whatever escape or facile happiness comes our way (“despair’s greatest hiding place”, warns Kierkegaard), we can’t hide forever. Sooner or later we must face facts. Samuel Beckett, a great chronicler of suffering, put it this way: “a man like me cannot forget, in his evasions, what it is he evades” (Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable, 1955). As for the brute fact of our own mortality that other literary Samuel, Johnson, says it “concentrates the mind wonderfully.” We might even say, after Wallace Stevens, that ‘Death is the mother of beauty’ (Harmonium, 1923).

Indeed, for Samuelson, there can be no growth, no progress, no enlightenment, no good, no truth, no room for others, no hope for self-overcoming, no authenticity, no beauty or its appreciation, without death and its faithful attendant, suffering. In saying this he aligns himself with the longstanding imperative that ‘to philosophize is to learn how to die’ – not only in the sense of coming to terms with physical mortality, but in the moral obligation to kill off as much ignorance, stupidity, and small-mindedness in ourselves as we can. At times, though, and especially in his chapter ‘Interlude on the Problem of Evil’, Samuelson sounds positively Panglossian in his faith in better things to come – as when he ruminates counter-fablely on the plight of Laocoön, the loss of the Trojan War, and Aeneas’s eventual founding of Rome: “had the innocent Laocoön not suffered, there would be no Rome. No tragedy, no civilization. No pointless suffering, no humanity” (p.115). Thanks Laocoön! But for me this is a claim as silly as it is unconvincing, at least when it comes to the search for meaning. Here it’s worth bearing in mind the argument of the contemporary philosopher John Gray, who finds zero evidence for cumulative progress in the realms of ethics, politics, civilization; generally, in our so-called ‘humanity’. Whatever our current achievements in these areas, they remain ever in a state of precariousness, as history has shown time and again. It’s also worth bearing in mind a notion ascribed to Tennessee Williams: “Every path is the right path. Anything might have been anything else and had just as much meaning to it.”

Inconclusions

To paraphrase Walter Benjamin, we exist perpetually in a state of emergency. This means that whatever remedy there may be for the next major crisis (fingers crossed), we cannot keep yet another catastrophe from coming round the corner. Still, with Covid, we were strongly reminded that the discoveries of science are crucial to our hopes. But so too are the humanities (including our blues understanding), which have long helped us to face what cannot be fixed, whether natural disasters, deadly viruses, social unrest, or the inevitability of death. For Merleau-Ponty, one such saving grace of the humanities is ‘true philosophy’, which, he says, “consists in relearning to look at the world.” This is precisely Samuelson’s intent with this study. In nodding to Wallace Stevens’ poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird, the title of Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering implies that a monochromatic account of suffering would be as limited as seeing a bird of mystery as only black.

Then again, maybe a single view of suffering will suffice after all. Maybe it’s enough to say, with James Baldwin, that “People who cannot suffer can never grow up, never discover who they are” – and leave it there. Or maybe we should all listen to The Smiths’ ‘Suffer Little Children’, and remember that some people can never grow up, never discover who they are, because they suffered too horrifically, and died way too soon.

© Doug Phillips 2022

Doug Phillips teaches existential literature and philosophy at the University of St Thomas in St Paul, Minnesota.

• Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering: What Philosophy Can Tell Us About the Hardest Mystery of All, by Scott Samuelson, University of Chicago Press, 2019, $25 hb, 270 pages.