Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Classics

The Birth of Tragedy by Friedrich Nietzsche

Rose Thompson relates a redeeming myth by Friedrich Nietzsche.

“Greek art, and Greek tragedy above all, held the destruction of myth at bay” – Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), who would on occasion be a little bombastic, referred to art as “the highest task and the truly metaphysical activity of this life.” As an atheist, he believed that existence could be justified, or life worth living, only as an aesthetic phenomenon. But it was Greek art, notably, fifth century BC Greek tragedy, that he revered most highly. Think Oedipus Rex, Hecuba or The Oresteia Trilogy by the great tragedians Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus respectively. In Oedipus, the title character unwittingly fulfils a prophecy in which he kills his father and marries his mother. The play ends with Oedipus gouging his own eyes out. Obviously it’s pretty bleak. But the Greeks couldn’t get enough tragedy; and neither could Nietzsche.

Nietzsche’s response to the paradox of tragedy – the seemingly inexplicable fact that it can be pleasurable to watch human calamity unfold – revolves around a polarity and fusion of what in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) he called ‘Apollonian’ and ‘Dionysian’ forces. Apollo was the Olympian deity of light, sculpture, and any dreamy, celestially-raised art form. A lucid dream – one in which the dreamer knows they’re dreaming, but wants to go on living in it – is a paradigm of Apollonian pleasure. We know it is unreal and the frontiers of reality are clearly signposted, but it still provides an ordered, desirable experience.

Whilst the Apollonian belongs to the individual, the Dionysian draws the individual closer to the muddied ground of unified human experience. Dionysus was the Greek god of wine, revelry, and unbridled passion – the Earth-bound ecstasies. According to Nietzsche, the Dionysian artistic impulse is best understood through an analogy to intoxication, either under the influence of alcohol, or other fertile terrestrial delights, such as dancing or the onset of Spring. Nietzsche’s core idea in The Birth of Tragedy is that in Greek tragedy, these two artistic forces merge: Apollonian idealism and artistic grandeur fuses with the Dionysian imitation of the chaotic human will. The Apollonian effect rises beyond the heavens in imagination, whilst the Dionysian is tethered to the Earth through passions and emotions. The audience are then enraptured in a shared redemption as human suffering is elevated to the divine through exquisite prose and music.

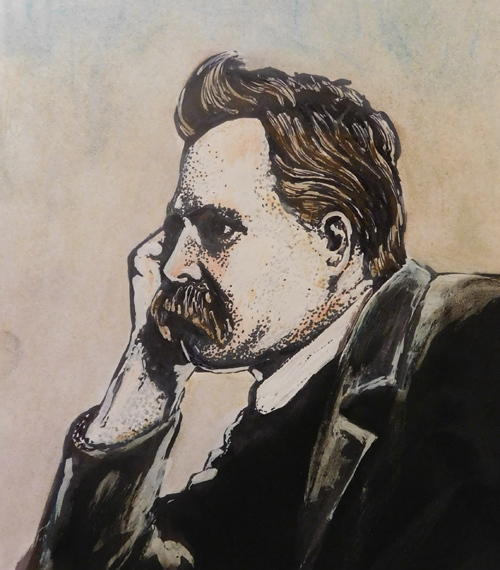

Nietzsche © Woodrow Cowher 2023 Please visit woodrawspictures.com

Humans desire a myth that coexists with our reality, in order to make the latter bearable, and to help us navigate it. Nietzsche believed that Greek tragedy was in a class of its own in this respect because in it the myth is revealed, rather than veiled, as it is in some religions, and Greek mystery cults. Nietzsche also here discloses the origin of a rapture that yields a sense of purpose. For Nietzsche, tragedy is the equivalent of staring nihilism in the face – except instead of turning away from life, one pours one’s existential dread into an artistic medium. Tragedy provides a metaphysical consolation and a catharsis. It provides a myth for myth’s sake, that is not met with cynicism but rather, with a sobering willingness to entertain it for what it is. It is a necessary illusion that transfigures the sharpest-edged reality into something more, even something beautiful.

Nietzsche blamed Socrates for the death of Greek tragedy – or more exactly, he blamed Socrates’ and Euripides’ enlightened devotion to reason and rationality. Euripides, the ‘critical thinker’ playwright, felt disconcerted and thus offended by the overly grand language, structure, and enigmatic choruses of his predecessors’ tragic creations. In his own theatrical work, he sought a consoling companionship in none other than the great Socrates, who shared his disdain of the genre. Socrates could never grasp tragedy, and thus, could not respect it. Under Socrates’ influence, Euripides dared to pursue a new kind of art – and, according to Nietzsche, with this pursuit came the destruction of myth and the rise of the ‘theoretical man’.

The Birth of Tragedy consists of a twofold argument. The bulk of the text contains Nietzsche’s controversial thesis about the birth, nature, and demise of Greek tragedy, but in the final chapters he creates a manifesto for the reformation of contemporary German culture. Linking the Socratic rationalism which purportedly destroyed Greek tragedy to the decadent state of modern German life, Nietzsche argues for one myth over another: the myth of art over the myth of scholarship (or science). His attack on rationalism and his idolisation of myth undoubtedly vexed scholars, but also attracted the ire of the novelist Thomas Mann, who criticised Nietzsche for preferring ‘instinct over intellect’.

As Nietzsche’s main thesis could not be tested, The Birth of Tragedy was itself regarded as unscholarly, and thus his aim to influence classicists and to instill a new impetus for cultural reform failed. Nonetheless, it’s hard to deny the seductiveness of Nietzsche’s argument, especially when his own reading reads like a late Romantic prose-poem. Had it not been dressed in a scholarly cloak, it would have been considered a masterful work of art in its own right. To paraphrase Nietzsche’s own Attempt at a Self-Criticism (1886), he should have sung this ‘new soul’ of art, not spoken it.

© Rose Thompson

Rose Thompson is a writer and student of philosophy.