Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

On Being One With Nature

Niki Young tells us how we (humans) can look at our relationship with Nature in a way that neither alienates us from it nor indistinguishably absorbs us into it.

Given that our current ecological situation is to say the least not desirable, we often hear people claim that we need to ‘save Mother Nature’, or that we have managed to ‘destroy Nature’, or alternatively, that ‘we are part of Nature’. Hidden behind all such assertions lies the tacit assumption that there is either a fundamental fissure separating humans from Nature (hence the claim that we need to save ‘Mother Nature’ or what have you), or an essential relational bond between humans and nature (hence the claim that we are ‘part of’ or ‘intertwined’ with Nature). I am of the view that both these positions are deeply problematic. This is because both start off by implicitly assuming that there are two and only two different kinds of entities, namely humans and everything else, and that these two entities either need mediational bridging (as with the former position) or are always conjoined (as with the latter). For reasons I’ll explain in a moment, the eminent American philosopher Graham Harman calls such positions ‘onto-taxonomical’. I hold that coming to terms with the current environmental crisis requires us to abandon such forms of thinking, and reconsider not only our specific position in relation to ‘the world’, but also the very status of the world which we tend to treat either as an adversary, or victim, or as that which simply serves to mediate human relations. In what follows, I shall discuss these issues in relation to Harman’s forceful critique of ‘onto-taxonomy’ as well as some proposed solutions to this flawed form of reasoning.

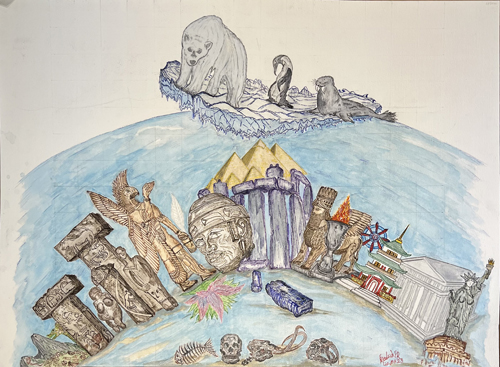

Climate Wisdom? Friedrich Farshaad Razmjouie, 2023

Ontology is the branch of philosophy involving the study of what it means for something to be or to exist. In other words, it tries to get at the very core of being as such. Taxonomy is the science of the classification of entities of a particular kind. What Harman calls ‘onto-taxonomy’ combines both these senses together, in that it refers to a deeply entrenched tendency to imagine that there is a categorical difference – or taxonomy – between different ontological domains; one reserved especially for human beings (who are not merely creatures belonging to a particular species, but rational moral agents) and their products (culture, creativity, and technology), and another reserved for everything else (nature, the world, or things). I, like Harman, want to criticise this distinction.

All such onto-taxonomic thinking may be understood to proceed in the following manner. It begins by pointing out some supposedly unique traits of human beings. One may think of rationality, speech, the ability to inherit a culture, create technology, tell the truth, or to politically repress, as examples of such traits. It then progresses to the unwarranted inference that these exceptional features bestow upon human beings an (at best) extraordinary or (at worst) superior ontological status, clearly demarcating our being from that of all other existent things. Onto-taxonomy is therefore anthropocentric, in that it assumes a strict categorical difference between humans and nature, or between the human-cultural and the natural. While I do not question that there are distinct differences I also hold that the special traits of humans do not support there being a difference in kind between humans and everything else.

To try to show this, I will use the work of Harman in order to deduce three interrelated solutions to such thinking. I hope that these proposals can help us to think more clearly about the current state of the planet. Perhaps they can help us forge a better path for humanity in nature.

Alternative Ontologies

The first step beyond onto-taxonomy involves adopting what might be called an ‘ontologically democratic’ view: one which doesn’t begin with the premature assumption of a categorical distinction between the natural and the technological or cultural. It does not assume that there is some overarching super-entity called ‘Nature’ to which humans are either opposed or interconnected. Instead, being itself – what exists – is entirely composed of a myriad of unique and singular ‘objects’ (this is why Harman’s position is called ‘Object-Oriented Ontology’, or OOO). Each of these objects constitutes part of our environment, and every single one of these things commands equal dignity as objects. In other words, all objects are all objects equally, and each constitutes an irreplaceable reality which affects its surroundings in its own unique and often unpredictable ways. Human beings are no exception here. This picture helps us resist the temptation to look at the environment as something merely complementary or antithetical to the human. Instead, we should see the world as composed of a decentralised and loose alliance of interrelated distinct and different entities, including human beings, with each of them maintaining a degree of vitality beyond the current context within which it operates. After all, each and every particular entity can – and often does – break loose from old alliances and form new ones, even when humans are nowhere to be seen.

A second step beyond onto-taxonomical thinking might be dubbed ‘ontological accretionism’. This involves rejecting the rigid distinction between natural substances and artificial composites, as postulated by philosophical giants such as Aristotle and Leibniz. This distinction creates a hierarchical two-tiered theory of nature, containing one fundamental layer of basic or natural entities, and another, derivative, layer of artificial, relational, or technological aggregates. This is problematic, since it would tacitly negate the above-mentioned ontological democracy. It would imply that entities which are one and/or natural are in some sense more real or ultimate than entities which are multiple and/or constructed. As opposed to this separation between entities which are one and entities which are many, ontological accretionism involves the idea that every entity is simultaneously both a unity and an aggregate sum of parts.

To take just one example, the computer in front of me is a relatively autonomous object that operates as one object, and it is also separate from me, or from any other entity to which it relates. After all, in most circumstances, I can always move it into an utterly different context without it becoming something entirely different. Nevertheless, the computer is also fashioned as a relational composite of its various internal components. (This, in my view, holds true for every sort of entity, except the truly fundamental constituents, supposing there are any).

A selection of objects

Image © Udo Grimberg Creative Commons 3 2010

Furthermore, entities can enter into new relations, thereby forming new paradoxically composite yet unified entities. Very often, such entities can be hybrids, in the sense that they can be composed of natural, cultural, and technological elements all at once. Once again my computer proves to be a good example, especially if we consider all the sorts of elements involved in its creation and maintenance.

What ontological accretionism shows is that there is not a ‘two-world’ difference or basic relation between humans and the world, or between the artificial and the natural. Rather, the world is multi-layered, composed of complex strata of endlessly varied entities, which at once both emerge from their composite parts, and go on to form new entities through alliances with other things.

Finally, we can take a third step beyond onto-taxonomy, with what can be dubbed ‘non-reciprocal entanglement’. This is the view that entities populating a given environment are often entwined with each other, forming loose yet powerful alliances. Thus humans are intimately connected with many other entities, insofar as we are part of that infinitely large network of entities loosely, and perhaps misguidedly, grouped under the heading of ‘the world’. Those entities often improve our lives in many ways, while some have the capacity to damage us irrevocably. In this context, we might even wonder whether ethics belongs solely to the sphere of human relations. Might it not be the case that my relationship to a simple boulder in the middle of a path is also partly ethical?

Taking cue from Alphonso Lingis’s great book The Imperative, it would be possible to claim that much like my relationship to my human peers, the rock places limits on my behavior, and commands me to behave in different ways, constraining the ways I move around or over it. We could however also expand Lingis’s insight beyond human-object interactions in order to argue that all entities – humans included – present to each other what he calls ‘imperatives’, forcing them to take each other seriously, pushing them to ‘negotiate’ and ‘translate’ one another in novel and often unpredictable ways.

Yet it’s important to emphasise that the fact that all entities in the ‘world’ are entwined and entangled does not mean that they’re holistically interrelated as one single big ‘megaobject’, and therefore reducible to their relations or actions. This is partly because elements in a given system are always entangled in an asymmetrical manner. Some entities form deeply enmeshed symbioses, but this does not always occur. For instance, while a parasite is thoroughly dependent on its host for its survival, the converse does not hold.

Conclusion

Thinking clearly about the nature of the world does not require us to think of ‘Nature’ or ‘the World’ as something to which we human beings are opposed, nor as a holistic web within which we are intrinsically and indistinguishably intertwined. Instead, we should see existence as consisting of the constant coming into being, recombination, and destruction of irreplaceable singular entities, with each of these entities throwing their own unique weight in the cosmos. This new ontology can give us a better attitude to the natural world, by helping us see both that we are individual beings and agents of change, but also just one type of object amongst all the others. We’re all in the same metaphysical boat, you could say.

© Niki Young 2023

Niki Young is a Philosophy lecturer at the University of Malta.