Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Social Media

Plato’s Cave & Social Media

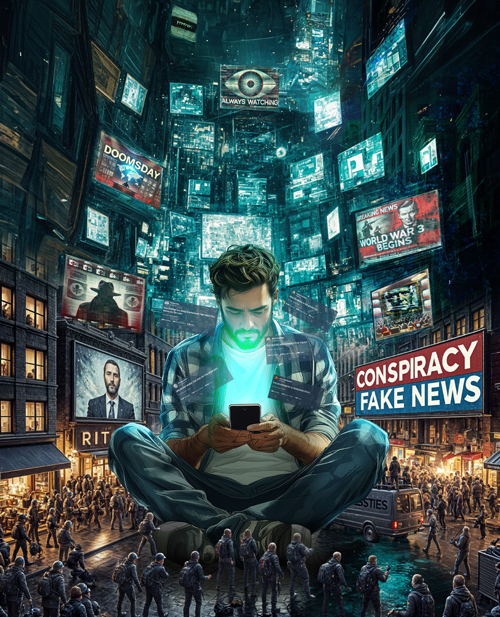

Seán Radcliffe asks, has Plato’s Allegory of the Cave been warning us of social media for 2,400 years?

The ‘Allegory of the Cave’ is a Socratic argument recorded by the Greek philosopher Plato, a student of Socrates, and the writer of The Republic (c.375 BCE), which contains a dialogue between Socrates and Plato’s brother Glaucon. The Allegory is a metaphorical story in which prisoners are chained up in a cave, facing a wall. There is a bright fire behind them, so the prisoners can see the shadows of people and objects that pass behind them that are cast on the wall. These shadows are the only reality they know, until one of the prisoners escapes to the outside, real world. Socrates argues that the freed prisoner would return and try to liberate his fellow prisoners, now knowing what exists outside the cave and how their reality is distorted. However, at the discussion’s conclusion, Socrates and Glaucon agree that the other prisoners would likely kill anyone who tries to free them, as they would not want to leave the safety and comfort of their known world.

For more art by Cameron Gray, please visit parablevisions.com and facebook.com/camerongraytheartist

In many ways, social media can be seen as a modern day version of the cave. We are bombarded with information, opinions, and images that are carefully curated by algorithms and presented to us on a screen. Like the prisoners in the cave, we can become trapped in the limited perspective this engenders, mistaking the shadows presented to us for the real thing. These shadows thus represent the fake news, conspiracy theories, and propaganda that is spread by social media. Indeed, the way in which we perceive and understand reality has undergone a radical transformation. So while the internet has given us access to an unprecedented amount of information, social media platforms have become the dominant medium for sharing and disseminating that information. Social media has become the primary source of knowledge for many people. However, the question remains: Will we ever know what is real in the age of social media?

On a broader scope, some thinkers in the area of ontology (the study of what exists) suggest that what we perceive as reality is not fixed or objective, but is socially constructed. This means that what we consider real is subject to change based on cultural norms and historical context. For example, unicorns are not considered real in our current society, but were accepted as real in older cultures. Therefore, the idea of what’s real is dependent on our current ontological framework, and cannot be universally applied.

In a similar vein, the Indian philosopher Adi Shankara (c.700-750 CE) argued that the world we experience is ‘maya’ – an illusion created by our own minds. According to Shankara, our senses and our intellect create an appearance of a world that’s separate from ourselves, but in reality, everything is Brahman, or the ultimate reality, and we are part of that ultimate reality.

At the heart of this inquiry lies the paradox of perception and knowledge: How can we know what is real when our perceptions are inherently subjective and fallible? Most philosophers think that reality exists independently of our perceptions, and that we can come to know it through reason and empirical investigation. Others contend that reality is nothing more than our subjective experiences, and still others, that we can never truly know what is real. I believe that we need to recognise the interdependence of perception and knowledge. Perception is not simply a passive reflection of reality, but an active engagement with the world that’s shaped by our experiences and beliefs, and which shapes them in turn. Likewise, knowledge is not an objective or perspectiveless representation of reality, but a product of our cognitive and social processes. Therefore, to understand what is real, we must recognise the complex and dynamic relationship between perception and knowledge. We must also cultivate critical thinking skills and engage in rigorous inquiry to refine our understanding of the world. Ultimately, the pursuit of truth requires a willingness to embrace uncertainty and ambiguity. We may never know with absolute certainty what is real, but by engaging with the world thoughtfully and critically, we can come to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

Notwithstanding all that, the scandal of knowledge is the fact that we do not know for sure if there is a reality outside of our own perceptions of it. However, both the Allegory of the Cave, and my hypothesis concerning social media, place us on the outside looking in at a world within our world, rather than looking outside.

Social media is becoming a second world, and a dangerous one. People can create an online profile which is almost a second identity. In this way, Plato’s Allegory is not too dissimilar to our current digitised state. In both cases, we’re talking about two worlds, the first being false and manufactured, but reality to the people within it; and the second being real (by our standards), and it contains people who can also recognise the first world as inauthentic. Reading Plato’s Allegory, we can see the absolute anguish of the prisoners in the cave, yet I believe that we have already entered a social media version of it. In the Allegory, people in the cave mistake the shadows on the wall for reality. Similarly, on social media, people often present themselves in a highly curated and filtered manner, projecting an illusion of reality that’s not authentic. In such ways, social media can create a distorted sense of reality, leading individuals to become disconnected from actual reality. But not only does social media restrict what we see and curate our views for us, it also poses a threat to democracy, sustainable development, freedom, and security.

The Allegory of the Cave explores the idea of confirmation bias. The prisoners in the cave are only exposed to one perspective, and do not know anything beyond the shadows on the wall. Similarly, social media can create an echo chamber, where people only see information that confirms their beliefs and opinions, leading to a lack of exposure to diverse perspectives and a reinforcement of their existing biases. The Allegory also highlights the concept of groupthink, where people follow the same beliefs and opinions as others in their group without questioning their accuracy. This phenomenon is frequently seen in modern society, where people often follow the opinions of their peers or a particular group without examining them critically. Furthermore, the murder of the freed prisoner by the others, predicted by Socrates, anticipates the modern rise of cancel culture, where we wield our moral pitchforks with narrow-minded fervour against our ideological ‘enemies’ – that is, anyone who disagrees with our view of reality.

Social media addiction has become a significant problem, with individuals becoming so reliant on likes, shares, and engagement that they’re unable to disengage from their devices. Plato, also, suggests that the prisoners are unable to free themselves from their captivity, being in chains, and are addicted to their illusions.

In the Allegory, the prisoners are under the control of external forces that manipulate what they see and hear, by determining what shadows are cast on the wall and the accompanying sounds. In the same way, social media is often manipulated by external forces such as algorithms, advertisers, and political groups, that influence what individuals are exposed to and how they perceive the world around them. As Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble (2011), explains, “In a world where the algorithms that determine what we see are largely opaque, we need to be very careful about what we're being served up.”

The Allegory explores the difference between perceived reality and true reality, and how our understanding of reality can be distorted by our experiences and perceptions. Just like the shadows on the cave wall, the information and news we receive through various media channels can be incomplete and distorted, leading us to believe a certain distorted version of reality. The creators of social media apps have essentially built a cave for us, and we seem to have submitted to its chains. We often rely on what we see on social media or news outlets without investigating the truth behind it. The Allegory thus points out the importance of having a critical approach to the information we receive, in order to have a more accurate understanding of reality.

In conclusion, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave provides a compelling analogy, and warning, for the dangers of social media. It highlights how social media can create a distorted sense of reality, reinforce existing biases, influence us through external forces, lead to addiction, and disconnect individuals from reality. So while social media can be a powerful tool for communication and connection, it is important to be aware of its limitations and the potential for it to distort our perceptions. By looking at the whole picture, and by drawing on the lessons of the Allegory of the Cave’s reverse form of ontology, we can begin to navigate the complexities, even jeopardies, of social media, and work towards a more informed and enlightened understanding of the world.

© Seán Radcliffe 2024

This essay won Seán Radcliffe the 2023 Irish Young Philosopher Awards Grand Prize and Philosopher of Our Time Award. He is now studying Mathematics and Economics at Trinity College, Dublin, where is he also an active member of the University Philosophical Society.