Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Reality

Get Real

Paul Doolan reveals that the real problem with ‘the real world’ is knowing what ‘real’ really means.

It seems to me that we encounter two serious philosophical problems when we thoughtlessly use the term ‘the real world’. Firstly, what is ‘the world’? It is this problem that Ludwig Wittgenstein confronted in the opening sentences of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922):

1 The world is all that is the case.

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by their being all the facts.

If it is the case that the world is all that is the case, then we add nothing at all when we place the word ‘real’ in front of the word ‘world’. Here ‘real’ is implied by ‘world’. The world, being the totality of facts, includes everything that is real. Thus, in this article I will focus upon the second problem, namely, the enigma that confronts us when we attempt to pin down the meaning of ‘real’.

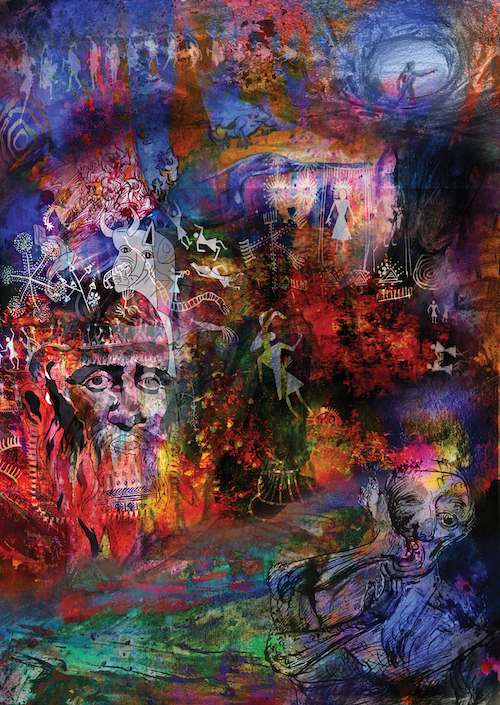

Plato’s Modern Cave by Venantius J. Pinto, 2021

Experience vs Reality

Only solipsists deny the existence of a reality beyond the experiencing subject. Through our senses, we encounter the physical reality that Immanuel Kant referred to as Ding-an-sich – the thing-in-itself. The ‘thing-in-itself’ is the world as it exists independent of our experience of it. However, our knowledge of the thing-in-itself is limited, and therefore imperfect. Consequently, we can never claim to know the world as it really is. Rather, we know it as we are, equipped with certain senses that have evolved to give us certain types of information about the world. Some creatures are equipped with visual apparatus that allows them to perceive longer- or shorter-wavelength light waves than we can observe, Bees can see in ultraviolet, for example. The world looks different to them than it does to us. Some creatures encounter the external world mainly through non-visual sensors. The aspects of the world sensed by bats are different than aspects mapped by human senses. In this sort of way, our experience of ‘the real’ is shaped and constrained by what we are. Ours is simply a different experience of the thing-in-itself than that of the bat.

The constraints placed upon us through our humanness might be highlighted by considering John Cage’s Organ2/ASLAP (As Slow as Possible). This piece of music commenced being played on a specially-built organ in Germany in 2001, and is planned to finish in 2640. It undergoes a chord change every few years. If you visit, most likely all you will hear is a constant drone. No one will ever hear the complete melody, simply because of the constraints of the human lifespan – no one lives for 639 years. However, for a being whose life spans many thousands of years, Cage’s piece might sound positively catchy.

The British empiricist David Hume argued that the subject or perceiving individual consists of nothing more than ‘fleeting impressions’, a belief echoed in Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon : ‘All you touch and all you see/ Is all your life will ever be’. By contrast, Kant argued that our impressions of the world are not chaotic and fleeting, but on the contrary are ordered by our mental apparatus, independent of, indeed prior to, the sense experiences themselves. In this way, human knowledge does not originate in our impressions of the real world simply acquired through the senses. Rather, our knowledge of the world consists of phenomenological (sensory) experiences which have been specifically shaped before they provide our encounter with the noumenal (or independently real) world by various mental ‘Categories’ as Kant called them, such as duration, or cause and effect. We never observe causation directly, for instance, but our experiences of nature are formed through the filter of seeing things in causal terms. Space and time are similar ‘ a priori intuitions’, in the sense that everything we experience of the world we experience as being in space and time.

However, the human is not simply a subject who knows the noumenal through preprocessed phenomenological experience. There is a third layer to our experience of the real. We are thrown into a world of symbols that envelope our lives in tangled network of meanings. Humans dwell not simply in the space where the noumenal and phenomenal intersect, but in a symbolic reality. The human is enveloped into linguistic forms, artistic images, symbols and rites, to such an extent that we “cannot see or know anything except by the interposition of this artificial medium” (Ernst Cassirer, An Essay on Man, 1944, p.43).

The symbol systems of art, rites, rituals and most of all language, frame our experience and produce meaning. Without this framing we would be unable to distinguish the real. We use language to grasp and give definite shape to the external world in our minds. But language in turn moulds our perceptions and concepts. Our symbolic systems do not mirror reality perfectly; they are creative, going beyond the pure representation of sensory experience to help us orient ourselves as beings in the world.

Reality vs Illusion

Thanks to this, we also have the capacity to produce illusion. Ironically, the closer we come to creating accurate representations of the real, the further the real recedes. The representations we create with increasing verisimilitude are becoming stand-ins for the real. The danger is that the representation eventually replaces the real entirely, the realistic illusion alone remaining.

Some philosophers argue that technology is a sword that will put the real to death. Gianni Vattimo, for instance, warns of technology trying “to impose its own version of the world as the sole possible reality” (The End of Modernity, 1930, p.30). Technology certainly provides a way of rearranging the world so we do not have to experience the real. I go from my apartment to the underground car park, then drive to another underground car park, take a lift to my office, and spend the day interacting with the world via a screen. Eight hours later I drive to the underground car park of the supermarket, and having bought packaged preprocessed food, I drive home to the machine that I live in. A machine heats the food, which I eat while I watch a streamed movie. Or, I simply spend the working day on Zoom and order food online. The Flemish architectural theorist Lieven De Cauter describes this world as ‘the capsular civilization’. He maintains that an ‘ecology of fear’ shapes our technological cities, ensuring we are ‘sealed against the real’ (The Capsular Civilization, 2004, p.29). The media philosopher Marshall McLuhan also warned that media technologies ‘work us over completely’ leaving ‘no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered’ (Understanding Media, 1964, p.26). So what happens when technology allows our media representations of the real to replace the real? In his 1971 song ‘Life on Mars’, Bowie sang that “the girl with the mousy hair… is hooked to the silver screen” – much as most of us are now. Later, in the song ‘Andy Warhol’, Bowie sang “Andy Warhol, silver screen/ Can’t tell them apart at all”. The philosopher Simon Critchley argues that Bowie’s lyrics “strip away the illusion of reality in which we live and confront us with the reality of illusion” (On Bowie, 2016, p.24).

In Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), the eponymous protagonist gains eternal youth while his painted portrait is scarred horribly by accelerated aging. A 2021 online reinterpretation, directed by Tamara Harvey, adds an unsettling twist. The would-be influencer Dorian Gray downloads a filter onto his phone with the result that all selfies on his Instagram feed and videos on his YouTube channel represent him as being startlingly beautiful, much better looking than in the real world. The number of his followers goes through the roof. Dorian becomes a recluse, stuck behind his keyboard, presenting his mesmerising face to the world while his flesh deteriorates due to accelerated aging. The portrait/illusion remains beautiful while the real Dorian Gray grows hideously ugly, and the public that consumes the images ‘can’t tell them apart at all’.

Reality vs Simulation

There’s nothing new about confronting the difficulty of distinguishing between the unreal and the real, between appearance and reality. Much of Plato’s later thinking, for instance, was an attempt to separate appearance and reality. For Plato, the opinions of the many refer to the world of mere appearance. Beyond appearance lies the real. But few gain access to the real. The many, wrapped in their opinions, live their lives as prisoners as if in a dark cave observing shadows cast on a wall. Few will turn their heads and find that they are being fooled. Even fewer will escape to stumble out of the cave and emerge into the light to encounter the real. Yet one only understands that one has been a prisoner in a cave when one is forced to experience the real.

Susan Sontag warned of the danger of stepping back into Plato’s cave by allowing photographic technology to bring about a world where images occlude the reality represented (On Photography, 1977, p.3). Timothy Morton argues that the shadow plays we obsessively watch on our screens have become ‘a contemporary version of Plato’s cave’, in which we are ‘trapped in an oppressive and boring reality’ (Humankind, 2017, pp.37-38). Jean Baudrillard argued that technology’s ‘race to… realistic hallucination’ will eventually lead to the ‘murder of the original and thus to pure non-meaning’ (Simulacra and Simulation, 1981, pp.107-108). The creation of this ‘hyperreality’ leads to the disappearance of the real, hidden behind an image ‘more real than the real’ (p.144). As Bowie prophesied, it becomes impossible ‘to tell them apart at all’.

Baudrillard argued that we have already replaced the real through technology which produces a simulation of the real. One contemporary celebrity who embraces the idea that we’re living in a computer simulation is Elon Musk. The possibility that his billions of dollars are not real may offer consolation to the envious. Except, alas, this means that we are not real either.

The theory came from Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom’s article ‘Are You Living In A Computer Simulation?’ (Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 211, 2003). Bostrom pointed out that we have amassed huge computing power already, then asks us to imagine a future human civilization that has truly gigantic computing power at its fingertips. He argues that such a civilization would definitely run a simulation of human history, for research, or even just to enjoy watching the development of their primitive ancestors (us). The simulation would be indistinguishable from the real, except that it could be stopped on a whim of the future scientists. Bostrom argues that there is no way for you to tell if you are already part of such a simulation, or if you’re the real thing.

In John Lanchester’s recent short story collection, Reality and Other Stories (2020), he tells a tale of four university lecturers who meet in a crowded café. They sit in an alcove hidden from the young customers and staff. Their conversation revolves around their insufferable students, how social media has made them all worse, and made everybody (except themselves) more stupid. They come up with the idea that social media succeeds so well at bringing out the worst in us it must have been designed by some evil entity running a simulation. One of them hopes for the evil demon to tweak the experiment, causing the stupid people to disappear while the intelligent are left. I won’t spoil the story by telling you how it unfolds, except to say that you need to be careful what you wish for, even in a simulation.

Could the simulation hypothesis be correct? In 2021, Scientific American ran an article confirming that, yes, we do indeed inhabit a simulation. However, you might be relieved to know that article ran on April Fool’s Day. The ‘good’ news is that climate catastrophe will render human civilization dysfunctional long before we gain the power to build a convincing simulation.

Physics vs Physicality

The simulation thesis emerges from a society that has embraced the metaphor of the computer and then mistaken the metaphor for the real. The idea that the real can only be comprehended by scientific experiment and mathematical formulae – or by Big Data crunched by massive computing power – partially explains our new obsession for STEM [Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths] subjects in education, and the assault on the humanities. During a recent lunch, I overheard a physics teacher proclaim that philosophy is utterly useless because all the theoretical problems will be solved by physics. I almost choked on my vegan sandwich. What did he think he was doing at that moment – physics, or philosophy? Blinded by uninhibited self-confidence, he was doing bad philosophy. Of course it is quite common to hear physicists boast that they are close to achieving a ‘Theory of Everything’. A fatal flaw, as Raymond Tallis cogently put it in this magazine, is that this will turn out to be ‘a theory of everything but the theorist’ (‘Reflections of a Metaphysical Flaneur’).

Our ‘love of the new’ approach to technology has led us to the mistaken view that the human brain is a computer, and that therefore a detailed understanding of what the brain computer does offers an insight into the real. After all, the current consensus on consciousness, according to Nobel Laureate Francis Crick, is that ‘it’s due to the correlation of some coalition of neurons’ (Susan Blackmore, Conversations on Consciousness, 2005, p.71). Alas, neuroscience still cannot tell me why the apple that I look at appears red, nor why that red apple tastes so fine. The failure is due to something basic: no one knows how neurons code information, and how that information gets turned into experience.

The technology-utopian and transhumanist Ray Kurzweil predicts that by 2039, we will be capable of uploading the human mind from the brain onto a computational substrate, thereby merging man with machine and achieving immortality. From this neurocentrist point of view, the human body below the neck is simply a means of transporting the brain to and from the science lab and the lecture hall. It ignores the fact that we are embodied beings and that sometimes thinking involves more than the brain alone. But for instance, viewing films of slaughterhouses might turn my stomach. A spooky house will give me the chills or give me goose bumps, and make me break into a sweat. Hiking in Switzerland provides breathtaking views, but sudden drops cause me to miss a heartbeat. Bad news makes my heart sink. This is more than mere grammar. In all these cases, thinking happens both above and below the neckline. We are beings-in-the-world. Skin forms a waterproof layer that efficiently packages my innards. Nevertheless, the outside world touches it, works on it, finds its way in. My skin is not just the border that divides me from the world; it is an entry point through which I experience the world, through touch. Gravity, despite my flights of fantasy, keeps me down to earth. No matter how high I jump, the ground beneath my feet breaks my fall. Millions of bacteria line my gut, I eat plants that have been sustained by sunlight. As Primo Levi told the story, a carbon atom that lodged in a cell of his brain had once been in the eye of a moth, had spent decades in a Lebanese cedar, and for hundreds of millions of years had been bound in a limestone rock. Or I awake, and feel Esther’s body next to me; I move a leg and I hear Neko the cat purring; I open my eyes and I see the window at a slant, and at that moment I smell the odour of fresh rain on the soil. After I get up, my first taste is of black coffee. What is real involves me even as it extends beyond me to represent the Ding-an-sich that I will never fully apprehend or fully comprehend. But I have no evidence that I am a brain in a vat being poked by scientists. Rather, everything about me and within me is real, and there is no clear border.

Conclusions & Implications

Most of this article was composed during day hikes along the Rhine valley in northern Switzerland. During these silent hours, I would find my mind returning to the question, ‘Does the term ‘real world’ make any sense?’ Each evening I would return to my study and work up my notes. Had I composed this within the four walls of the study it would have been a very different essay. The set – the state of my mind – and the setting – the environment that surrounded me – shaped my thoughts. Something about the rhythm of my walking stride released these words, the slow meandering of the majestic river shaped the long-windedness of my paragraphs. If there is anything worthwhile in these musings, the source lies as much in the fluidity of the river and the intelligence of the forest as in my brain.

We live embodied in the world, and ‘the real’ emerges out of our encounters with and within the world. Our encounter with the noumenal through our phenomenological experiences and our immersion in the symbolic provides a constant dialogue as we piece together aspects of the thing-in-itself, recalibrating, criticising, constructing, having another look, making it up…

The fact that we live in a biosphere led Timothy Morton to suggest the idea of the ‘symbiotic real’. This idea of the real attempts to counter our hierarchical tendency to exclude the non-human. Morton argues that all life forms depend upon each other and therefore relying-on ‘is the uneasy fuel of the symbiotic real’ (Humankind, p.2). The contemporary physicist Carlo Rovelli would agree. In a recent Intelligence Squared conversation with Philip Pullman (May 28, 2021), he said that the main lesson of quantum physics is that objects only have properties when they interact with other objects. In the entangled real, nothing exists by itself. Rovelli admits that these ideas were anticipated two thousand years ago by N ā g ā rjuna one of the giants of Indian Buddhist philosophy. N ā g ā rjuna attacked the idea of stable substances, criticising the concept that things had a nature of their own, arguing that ‘we can find no self-existence of the entities’. Instead, objects find their reality in a system, and are in themselves nothing. The real is characterised by interdependence and universal relativity. As Morton says, ‘relying-on’ fuels the real.

In Plato’s parable of the Cave, the illusory ‘reality’ which the prisoners observe is constructed by elaborate props manipulated by the jailers. Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that what keeps the prisoners chained to the shadowy images is ideology, and ‘they would do anything not to know it’ (Plato at the Googleplex, 2014, p.380). Similarly, the next time you’re tempted to suggest that teachers, politicians, or others should focus on ‘real world issues’, ask yourself, whose ideology is being served in the way ‘the real’ is being picked out? In fact, when you use the term ‘real world’ you are speaking nonsense. ‘Real’ can never predicate ‘world’, for what is ‘real’ is produced and exists within the world, not the other way around. And recognising what is real is itself not without problems.

© Paul Doolan 2021

Paul Doolan teaches philosophy at Zurich International School and is the author of Collective Memory and the Dutch East Indies: Unremembering Decolonization (Amsterdam Univ. Press, 2021).