Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Irish Philosophy

Irish Philosophy & Me

Catherine Barry charts her journey through historical Irish thought.

Some claim Britain as the origin-point of the Enlightenment. France and Germany are equally famous for their philosophy. But what about Ireland? Those particularly interested in philosophy may have heard of John Scotus Eriugena and George Berkeley, but probably no more than that. Ireland has not been seen as a philosophical place.

In 2013 I was dabbling in blogging. Just before St Patrick’s Day (17th March), I saw Berkeley and Irish Philosophy on a library shelf, and decided to post about Berkeley, the single isolated genius I expected to find in that book. I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I wasn’t expecting, for example, William Molyneux promoting Enlightenment thought in late seventeenth century Dublin. A correspondent with John Locke, Molyneux set up an Irish philosophical society on the lines of Britain’s Royal Society, and convinced the provost of Trinity College Dublin to add Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding to the syllabus.

As for John Toland, he was a shock to everyone. Born into an Irish-speaking Catholic family in Donegal, he left all that behind and became an advocate of ‘rational religion’ (that is, of deism), as he expounded in Christianity Not Mysterious (1696). The book, which argued that true religion includes no mysteries, caused a furore in both England and Ireland. When Toland arrived in Dublin in 1697 he found himself denounced from the pulpit. A few, including Molyneux, welcomed him, but after months of arguing in taverns and coffee shops, he left just before the Irish Parliament ordered his book banned and burned by the public hangman. Never to return to Ireland, Toland was later an editor of republican writings, a political philosopher supporting the Whigs, a pamphleteer for various political figures, and a hanger-on at the court of Sophia of Hanover.

Deprived of his presence, yet still jarred by the religious and political implications of his ideas, in Dublin much ink was spilled on explaining how exactly Toland was wrong, mostly drawing on the ideas of Locke. Thus was born ‘theological representationalism’, a theory of how we can know God. It was also the birth of the Irish Enlightenment, whose writers not only advanced their own versions of the theory, but criticised others. The younger generation, educated on Locke in Trinity and reared on these debates, developed their own ideas on other topics too, including aesthetics, ethics, epistemology, toleration, and political theory. Authors included Edmund Burke, Philip Skelton, and of course Berkeley (politically problematic then and now, though for different reasons). Added to the mix were Glasgow-educated Presbyterians, drawn to Dublin first by the Whig Robert Molesworth (Toland’s patron), and then by Francis Hutcheson. First part of the ‘Molesworth Circle’, and later, ‘the Father of the Scottish Enlightenment’, Hutcheson’s writings shaped a train of thought that led to radicalism, including that of the United Irishmen. There were also Irish thinkers more famous for their literary works, such as Jonathan Swift and Oliver Goldsmith. For the next sixty years, philosophical thought flourished in Dublin.

I was hooked. I raided the library for more books on Irish philosophy. Thomas Duddy’s A History of Irish Thought (2002) was a revelation. It spans centuries, from the sixth century Augustinus Hibernicus (the Irish Augustine) drawing on St Augustine to naturalise miracles (or make the natural miraculous), to the neo-Platonic genius Eriugena, the scholastic Peter of Ireland (likely teacher of Aquinas), and the theorist of dominion, Richard Fitzralph. Robert Boyle’s philosophical reworking of science gave way to the Irish Enlightenment, whose political and ethical debates flowed into the nineteenth century. Utilitarianism fuelled arguments for political and economic fairness, including votes for women (Thompson, Wheeler). But there were also reactions against utilitarianism. There was the idealism of Rowan Hamilton and idealistic anarchism of Oscar Wilde; there were heated debates on the meaning of Darwin for ethics and religion. The twentieth century yielded important work on ethics from Iris Murdoch, Wittgensteinian criticism of philosophy via Con Drury, and the ‘republican’ theory of contemporary Irish philosopher Philip Pettit. There is no shortage of Irish thought.

I was fascinated by this history I had not known. Wanting to share it, I set up the blog irishphilosophy.com. I’m still writing for it ten years on.

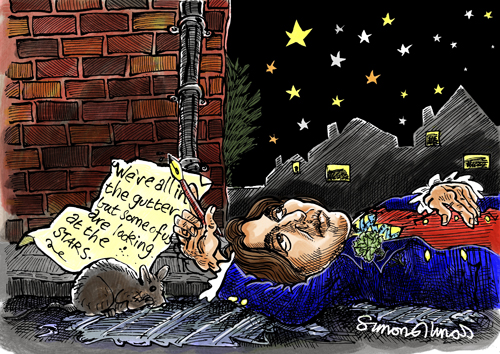

Oscar Wilde illustration © Simon Ellinas 2024 Please visit caricatures.org.uk

Cross-Cultural Connections

It intrigues me that, despite being a philosophy student in Ireland, I had known almost nothing about Irish philosophy. One reason surely lies in a particular view of Irishness. Matthew Arnold suggested that the Irish psyche was dreamy and romantic, in contrast to the hard-headed, rational Anglo-Saxon. This view of Irishness was popular even among Irish nationalists, perhaps all the more due to the contrast with the English. The result is a view that philosophy and science clash with the Irish psyche, despite the long history of Irish philosophy and science.

In The Irish Mind (1985), Richard Kearney outlines arguments from a debate in the 1980s about Irish thought and thinkers. Berkeley and Hutcheson were said to be “anything but typically and traditionally Irish.” The presence of their names in histories of British philosophy was used to argue that they were not representative of Irishness as such. Kearney’s description of John Toland as “the father of modern Irish philosophy” particularly ruffled feathers, proving that nearly three hundred years after his death, Toland was still capable of provoking a fuss.

The problem here is the positing of ‘British’ and ‘Irish’ as a dichotomy. Edmund Burke is an excellent example. His account of political representation and his criticism of the French Revolution are important in British political thought. He spent much of his time in Britain and was an MP there. Yet he was born and educated in Ireland, and was deeply concerned with Irish affairs throughout his whole life. Is he Irish, or is he British?

Given Ireland’s complex and contested history, why not replace ‘either/or’ with ‘both/and’? This accommodation is a principle Kearney attributes as being central to ‘the Irish mind’: “an intellectual ability to hold the traditional oppositions of classical reason together in creative confluence.” Duddy, commenting on the same debate, argues for an inclusive definition of Irish, including those who are ‘Irish by privilege’.

Another demarcation problem is between philosophy and non-philosophy. In his History of Irish Thought, Duddy includes writers of philosophical treatises, but also those better known for their literary works, such as Wilde and Yeats. Restricting ‘proper philosophy’ to academic treatises means excluding more marginal ideas – such as United Irishman Thomas Russell’s criticism of the aristocratic monopolisation of political power – and thinkers excluded from academic philosophy, notably women such as Lady Ranelagh or Maria Edgeworth.

Another contested term is the name of my blog: Irish Philosophy. Strictly, ‘Irish philosophy’ should refer to a practice where specifically Irish philosophers interact and develop distinctive ideas. This happened in the Irish Enlightenment; in the Trinity College school of Kantian translators and commentators; and in the Irish Franciscan collective work on Duns Scotus, for example. But the Irish Franciscans test the definition, since they were working in Leuven in Belgium, and in Rome. Duddy argues that an Irish history of ‘disruption, displacement, and discontinuity’ means that to look for an extended, continuous history of intellectual development purely in Ireland is to risk defining ‘Irish thought’ out of existence. By contrast, the Irish Philosophy blog embraces philosophy about Ireland or being Irish; philosophy created in Ireland; and philosophy done abroad by Irish thinkers. Writing it has taught me so much, and I owe a great deal to historians’ and philosophers’ generous sharing of information, notably on Twitter, now renamed X. It was there that I discovered the strange world of early Christian Ireland, absorbing classical learning and writing itself into the history of the world. It was there, too, that I learned about the seventeenth century Irish colleges on the European continent, and the Irish involvement in European debates. As for the rest, there are Irish neo-Platonists (so many that some see this as an essence of Irish thought!), socialists, radicals, free-thinkers, utilitarians, idealists, and so on. Geoffrey Keating described Ireland as “a kingdom apart by herself like a little world”, but the reality is that Ireland has always been open to the world – “appropriating all/The alien brought” as Louis MacNeice said of Dublin. From the classical learning of the sixth century to the philosophical currents of more recent times, the Irish have taken it in and made it their own.

They’re doing so still. Since my blog started, Philosophy Ireland was established to support the development of philosophy in the Irish curriculum, universities, and wider community. The first Young Philosopher Awards were held in 2017, and an optional philosophy course included in the Irish curriculum for 12 to 15 year olds. Some primary schools on both sides of the Irish border have introduced critical thinking into classrooms, and one in Northern Ireland has been celebrated in an award winning film, Young Plato (2022).

“We Irish think otherwise” said Berkeley when rejecting Locke. The study of Irish philosophy not only examines what we think and why we think it, but who ‘we Irish’ are; whether there’s something essential to being Irish, and what that may be. Like all history of philosophy, it shows how our concepts have changed, and throws our prior assumptions into question, including what it means to be Irish, and who is Irish and who is not.

© Catherine Barry 2024

Catherine Barry is the editor of the blog irishphilosophy.com and is @irishphilosophy on Twitter. A Hume Scholar in Maynooth University, she is working on a PhD on toleration in eighteenth century Ireland.