Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Philosophy & Literature

Milan Kundera’s Philosophy of the Novel

Mike Sutton reflects on the existential code of the novel.

As well as several striking novels, notably The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), the Czech-French author Milan Kundera (1929-2023) wrote extensively about the role of literature in philosophy. He saw fiction as a perfect vehicle for certain types of philosophy, particularly post-modernism and existentialism. “For me”, he said, “the founder of the Modern Era is not only Descartes but also Cervantes.”

Kundera was born in Czechoslovakia, and died in Paris last July, aged 94. He was heavily influenced by his background, especially by the Prague Spring of 1968, when the Czech government revolted against Soviet rule. The Soviets sent the tanks in to crush the rebellion. That year Kundera’s books were banned in his own country and removed from public libraries. He was befriended by the French publisher Claude Gallimard, but he stuck it out in Czechoslovakia until 1975, when Gallimard finally persuaded him to move to Paris. By that time he had also been sacked from his Czech teaching position and forbidden to work.

In his major work of literary criticism, The Art of the Novel (1986), Kundera says: “The novel dealt with the unconscious before Freud, the class struggle before Marx, it practiced phenomenology (the investigation of the essence of human situations) before the phenomenologists.” He quotes the Austrian novelist Herman Broch, who maintains: “The sole raison d’être of a novel is to discover what only the novel can discover.” And Kundera further claims, “all the great existential themes Heidegger analyses in Being and Time – considering them to have been neglected by all earlier European philosophy – had been unveiled, displayed, illuminated by four centuries of the European novel.” How does he support such claims? Let us examine his case for the novel in philosophy.

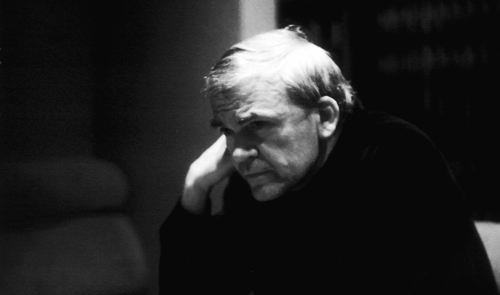

Milan Kundera © Elisa Cabot 1980 Creative Commons 2

Essentialism, Existentialism & the Novel

Much philosophy is essentialist, meaning that everyone and everything is taken to have a definable set of objective attributes essential to its identity. In its modern form, essentialism is, generally speaking, scientific, seeking empirical evidence, while also constantly using reason to question even the nature of empiricism.

The American pragmatist and postmodernist Richard Rorty, writing about Heidegger, Kundera, and Charles Dickens in Essays on Heidegger and Others (1991), points out the advantages of essentialism in philosophy, but claims that they’re mainly of benefit to science and engineering, not in descriptions of our emotional life. He supports Kundera, who, he says, seeks to show that where narrative, chance, and our relationships with other beings take over, essentialist argument ends. In novels as in human affairs, nobody has access to the truth. Rorty goes on: “it is precisely in losing the certainty of truth and the unanimous agreement of others that man becomes an individual. The novel is the imaginary paradise of individuals. It is the territory where no one possesses the truth.”

Essentialist philosophers following the Western tradition would see this state of affairs as disqualifying the novel as a vehicle for philosophy. At best, they’d see the novel as a way of illustrating essentialist principles already established through philosophy. But Kundera insists, “The rise of the sciences has led to what Heidegger called the ‘forgetting of being’… No one owns the truth and everyone has the right to be understood… The world of one single Truth and the relative, ambiguous world of the novel are moulded of entirely different substances.”

Who is right? Actually, the two views are not necessarily opposed, unless you believe that philosophy is restricted to essentialism. But – often to the chagrin of those philosophers who do believe that – as well as essentialism, philosophy also examines the sort of questions pursued by existentialists, who typically say that people have no essential, unchanging nature. And after the existentialists came the postmodernists and poststructuralists, whose writers, such as Lyotard, Foucault, and Derrida, argued that there were problems with an essentialist approach. There is indeed a case to be made for existentialism and postmodernism based on what really happens in life, and what part the concept of reason plays. Kundera is an unashamed postmodernist, and uses the novel to show where reason fails or is inadequate.

Does Essentialism Work For Life’s Problems?

Rorty and Kundera maintain that essentialism is good for science and engineering, but not effective for moral and emotional issues. For those, we need existentialism.

Kundera argues that many people desire a world in which good and evil can be distinguished. Religions and ideologies are based on this. The only way such people can cope with an otherwise morally ambiguous novel is via dogmatic rules. But, for example, is Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina the victim of a narrow-minded tyrant, or is he the victim of an immoral woman? Or is Franz Kafka’s Josef K (in The Trial, 1925), an innocent man crushed by an unjust Court, or does the Court represent divine justice and K is guilty? The novel makes no judgement. Rather, it sets out the way things really work in life. Kundera writes, “This ‘either-or’ encapsulates an inability to tolerate the essential relativity of things human, an inability to look squarely at the absence of the Supreme Judge. This inability makes the novel’s wisdom (the wisdom of uncertainty) hard to accept and understand” (The Art of the Novel). Describing the plight of individual characters is what the novel excels at, not the setting up of moral or other social rules. Kundera hammers this point home in another passage. Descartes’ and Bacon’s ambition for mankind was for us to become masters of the world through reason. But Kundera says, “Having brought off miracles in science and technology, this ‘master and proprietor’ is suddenly realising that he owns nothing and is master neither of nature (it is vanishing, little by little, from the planet), nor of History (it has escaped him), nor of himself (he is led by the irrational forces of his soul). But if God is gone and man is no longer master, then who is master? The planet is moving through the void without any master.” So the comforts and certainties of reason are questioned in the novel: “The novelist is neither historian nor prophet: he is an explorer of existence.”

The Plight of the Individual

What is this ‘being’ or ‘existential self’ that the novel investigates? What about the individual in this complex world?

Kundera illustrates his answer with two examples; one from Marcel Proust, who considers the history of an individual during a certain era; and one from James Joyce, who concentrates on the existence of the individual in the present instant. Both wrote indisputable masterpieces with memorable central characters – In Search of Lost Time (1913) and Ulysses (1922) respectively. However, in Kundera’s view, neither capture the existential problems he means. In Kundera’s estimation, Kafka comes closest: “Kafka… does not ask what internal motivations determine man’s behaviour. He asks what possibilities remain for man in a world where the external determinants have become so overpowering that internal impulses no longer carry weight?… The novel is not the author’s confession, it is an investigation of human life in the trap the world has become.” Put in other terms, there is no possibility of us escaping from our lives as we might escape prison or the army, and in life, each of us has problems with the world in which we live: “Man and the world are bound together like the snail to its shell: the world is part of man, it is his dimension, and as the world changes, existence changes as well… both the character and his world must be understood as possibilities.”

As I mentioned, for Kundera, the Prague Spring of 1968 forms a large part of his personal world, so it makes appearances in his novels, particularly in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. For that reason, he is sometimes considered as a political, or indeed a war, novelist – which he denies. He stresses instead that the Prague Spring formed the world in which the characters of his novels found themselves, and which presented for them unusual moral dilemmas and relationship difficulties. Given that background, and their propensity to behave in individual ways, they all react differently. Kundera is not judgmental; he does not try to identify moral right or wrong, or criticise the character’s predispositions to act in certain ways. The existential position they find themselves bound to is what is of interest to him.

The Role of Philosophical Writing

Given this stress on the flexibility of moral questions and their dependence on the character of a protagonist in a particular situation, what is the role of philosophical theories in relation to the novel?

Kundera’s view of the unique position of the novel as a philosophical narrative might lead us to expect him to ignore the philosophical canon itself. Nothing could be further from the truth. He makes great use of the history of philosophy, often illustrating some philosophical theory or idea by investigating how it plays out in particular practical situations. And in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, he spends time at the beginning of the novel describing Friedrich Nietzsche’s theory of ‘the Eternal Return’. In The Gay Science (1882), Nietzsche says, “The heaviest burden. – What if a demon crept after you one day or night in your loneliest solitude and said to you: 'This life, as you live it now and have lived it, you will have to live again and again, times without number; and there will be nothing new in it’?… the question… would lie as the heaviest burden upon all your actions.” Kundera’s interpretation of this is that while life is only lived once and we cannot do it again, nonetheless, in our minds, ideas and attitudes do recur, particularly when situations arise to test us. In life, though we may crave lightness, the dilemma of the Eternal Return is so universal that we are unable to avoid it, and it does indeed crush us. The Unbearable Lightness of Being is about the characters’ efforts to avoid this ‘heaviest of burdens’ – hence its gnomic title.

There are four main characters in the novel: Tereza, who is married to Tomas, a surgeon and philanderer; Sabina, who starts the novel as his mistress, and Franz, a later lover of Sabina. Tereza believes that things come back to haunt us, and she worries about and is influenced by past events. Tomas wants to lead a carefree life, but his love for Tereza, and the oppression of the Soviet regime, and the trouble he gets into because of his conscientious objection to it, condemn him to heaviness. Sabina wants to be light, carefree, but she ends up leading a lonely life in Paris, wishing for the return of her hedonistic past. Franz actually wants to be heavy – to show that he worries about the state of the world and is a caring person; but his innate lightness leads him to do it in an ineffective way, and he reaches a sticky end. They can each do no other than what they do, because of the situations they find themselves in and their particular characters. They are snails stuck in their shells.

Which is better, lightness or heaviness of Being? The question lies unresolved in the novel because it is meaningless, since none of the four main characters are successful in changing what they are, in spite of their desire to do so. To be heavy is burdensome, as it is with Tereza; yet to attempt to be light is futile, as it is with both Tomas and Sabina. Franz, who wants to become heavy, is equally unsuccessful. None of the characters in the novel are able to wilfully change their situations. In Ecce Homo (1908), Nietzsche has another famous aphorism: “ amor fati [love your fate]… bear what is necessary, still less conceal it – all idealism is mendacity in the face of what is necessary…”

What Has Kundera Taught Us?

From Kundera we can see that good novels are part of the philosophy canon. They have an ‘existential code’: they describe characters with complex motivations and are not concerned with simplifying theories. Kundera writes, “The novel’s spirit is the spirit of complexity. Every novel says to the reader: ‘Things are not as simple as you think.’” The comforts and certainties of reason are questioned in the novel. As in life, it is sometimes hard to identify right or wrong, or criticise individual predispositions to act in certain ways. The existential position we find themselves in is what ultimately accounts for our actions. We cannot escape our existential selves. “The world is part of man.”

In 1985 Kundera received the Jerusalem Prize, given to writers whose works have dealt with the freedom of the individual in society. Perhaps the final word should be left to his acceptance address, where he expands on some of the themes we’ve looked at, and considers afresh the job of the novel. The theme he stresses most is that “the novel is the imaginary paradise of individuals. It is the territory where no one possesses the truth.” He applauds the 'lazy liberty' of the novel. Nothing is legitimated beyond doubt, there are no efforts to develop grand narratives or theories, but instead there is a plot and characters which are used to examine concepts in the light of the complex and imperfect nature of human existence. Life is not a series of effects undertaken because of some cause, but a set of situations that arise because of chance, and because of characters’ individual dispositions to act in certain ways. Many novelists – Kundera mentions particularly Sterne and Flaubert – have celebrated stupidity. Reason may be there to understand cause, effect, and conscious motivation; but in the novel, as in life, reason can be undone by stupidity.

Kundera concluded his address with a ringing peroration:

“If European culture seems under threat today, if the threat from within and without hangs over what is most precious about it – its respect for the individual, for his original thought, and for his right to an inviolable private life – then, I believe, that precious essence of the European spirit is being held safe as in a treasure chest inside the history of the novel, the wisdom of the novel.”

© Mike Sutton 2024

Mike Sutton lives in Birmingham and writes about the importance of philosophy in science, technology, and social life.