Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Moral Issues

What My Sister Taught Me About Humanity

Lee Clarke argues that we need a more inclusive view of moral personhood.

On 21st April 2022, the then Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison answered the question of a lady with an autistic son during an election debate by saying that he was ‘blessed’ not to have had children with disabilities. The comment caused controversy, with many calling it upsetting and insensitive. What his comment also did, though, was get me to think about my own experiences with disability from a philosophical perspective. I am not disabled myself, and I specialise in Comparative Philosophy, not Philosophy of Disability. What experience of disability, then, do I have? It is rather, the experience I had with someone else that explains why I feel that I have a genuine stake in this debate.

My younger sister, Laura, who passed away in 2018, had severe mental and physical disabilities. After reading the literature around the Philosophy of Disability, it occurred to me, mainly as a result of the work of Eva Feder Kittay, that many philosophers get things about cognitively disabled people wrong. Some even exclude them from the moral community through the claim they lack certain attributes which make them a ‘person’, such as rationality. I wish to comment on these issues from a perspective derived from growing up with Laura, and argue not only that it can be a blessing to have a disabled child in the family but that cognitively disabled people should be said to have an equal moral status by challenging the idea that reason is the unique arbiter of what constitutes personhood. Instead, we require a much more inclusive view.

Laura by Lee

Laura’s Story

Laura was born on September 8th 1999 with the condition known as agenesis of the corpus callosum. The main characteristic of this is that the area that connects the two hemispheres of the brain is absent at birth. As well as this, she had a heart condition, and numerous other problems. She was unable to walk, talk, feed herself, or sit up properly, and was basically very much like a baby. Despite these issues, she was also very loving, knew people close to her, very communicative, self-aware, and possessed a personality. If we define ethics as how we should treat others on a moral level, growing up with Laura provided me with an ethical education outside the academy. I received it in two ways. The first was what I was taught by being the sibling of a disabled person generally; the other was what she taught me herself uniquely, through her own actions and personality.

Research says that growing up with a disabled sibling affects the non-disabled children in various ways, both positively and negatively. They’re at increased risk of mental health problems, for example. However, it is also generally agreed that the siblings of disabled people develop an increased capacity for tolerance, acceptance, altruism, and other positive emotions. Learning these positive qualities constitutes the first type of ethical education I and other people in the same situation receive. Growing up, I lived with someone who was perceived as different, and as I came to realise that, I was forced to confront the common ideas of normalcy people hold.

Indeed, as I came to appreciate and accept Laura’s apparent ‘differences’, I came to apply that same attitude towards others by default. In the same way as I did not see Laura as ‘different’ in any salient sense, I could not see why other people should be regarded or treated as ‘different’ for things such as race, religion, sexual orientation, gender, and so on. I’m not saying that people without disabled siblings cannot accept diversity too – as they should – but that siblings of disabled children are obligated to do so from an early age. I would say that acquiring such views in such a manner is distinct from, for example, having politically liberal parents. My experiences installed within me both a sense of radical acceptance of others and a hatred of discrimination and bigotry in all its forms. They also provided me with a sense of commonality with others. I’ll say more about this below.

The second way I was given an ethical education came from Laura herself. Among the many great things my sister taught me was a sense of a ‘something’ that I share with all other humans on the planet, which I will call ‘common humanity’, which could be classed as a form of cosmopolitanism. Obviously, I am not the first person to call myself ‘cosmopolitan’ (that was Kant) nor the first to act in accordance with this idea. Many great global philosophical traditions have advocated doing so; from Greco-Roman Cynics and Stoics to Indian Buddhists and Chinese Mohists. However, Laura taught it to me uniquely, because she did not (and could not) do so verbally.

My sister acted the same with everyone she met – always friendly, offering them a warm smile, and normally also a noise! I had friends and family from many different backgrounds, and Laura never acted any differently towards any of them. I cannot be certain, but it was as if she did not see any of the normal ‘differences’, such as those based on race, religion, nationality, etc, with which we categorise people, because she did not understand those categories. Of course, she was not completely impartial, and clearly felt more comfortable when I, one of my parents, or other immediate family were with her; but to me, it seemed that she just saw people as people, and acted in the same loving manner with all of them. When she met someone, the one thing she was sure of was that they were another human being: there existed a sense of common humanity between them and her. As I saw how Laura treated people over time, I also learned this from her. Indeed, it is such an idea, and encouraging understanding between diverse traditions and communities, that drives my philosophical work.

So, although there are negative aspects to growing up with a disabled sibling, and having a severely disabled person in the family is sometimes extremely hard, both personally and generally, for me these things are outweighed by the positive qualities the experience brings. I’m certain that I would be a completely different person if Laura had not been the way she was. I would have most likely been less tolerant, less open-minded, and less accepting. All of these qualities have contributed to me as a philosopher also. Although Scott Morrison may not have intended his remark in the way it has been interpreted (it was a poor word choice nonetheless), I would counter it by saying that it is indeed a blessing to have grown up with a disabled sister. It taught me that I should treat others with acceptance and kindness, and provided me with an ethical education before I even knew what ethics was.

Inclusively Human

What does all this have to do with the moral status of disabled people?

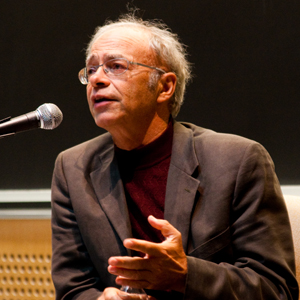

In his book Practical Ethics (2011), the Australian utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer suggests three key characteristics that make up ‘normal’ human beings, rationality, autonomy, and self-awareness (p.160). The possession of these, he says, determines who is entitled to moral status. Many other philosophers apart from Singer share this view. The problem for ethics arises when we realise that many cognitively disabled people could lack these things, or at least possess them in a significantly reduced degree compared with people without cognitive disabilities. Does this mean then that they should be treated differently from others in the human moral community – or even excluded entirely?

Peter Singer at MIT, 2009

Peter Singer © Joel Travis Sage 2009 Creative Commons 3

For reasons of space, out of Singer’s three concepts, I will restrict myself here to challenging the idea that the possession of a capacity for reason is necessary for a claim to personhood or ‘full humanity’. I feel that of the three, reason is the most influential. Although its ability to ascertain truth has always been challenged by mystics, it can be said that reason has always held pride of place in (especially Western) philosophy. Ever since Aristotle its possession has been assumed to be what separates humanity from non-human animals (and within humanity, as the thing that separates philosophers from other people!).

My intention is not to argue against the use of reason. On the contrary, as a philosopher, I advocate its use. I believe that people need to make more use of reason, especially in the current climate of misinformation and conspiracy theories. Yet some philosophers of disability, notably Eva Feder Kittay, whose daughter Sesha has some of the same limitations Laura had, have noticed that many common assumptions of Western philosophy – including the view that reason is necessary for a human status – run into problems when applied to cognitively disabled people. I identify a lot with Kittay when she writes the following (change the word ‘daughter’ to ‘sister’ for me, of course):

“How can one repeatedly read and teach texts that give Reason pride of place in the pantheon of human capabilities, when each day I interacted with a wonderful human being who displayed no indisputable evidence of rational capacity? How can one view language as the very mark of humanity, when this same daughter cannot speak a word? How can one read about justice as the consequence of reciprocal contractual arguments when one’s own child is unable and will apparently never to be able to participate in reciprocal contractual agreements?” (Learning From My Daughter, 2019, p.8).

Granted, most thinkers, including Singer, do not say that reason alone makes a person – but there are some who do adhere to this opinion, or who at least agree that to possess reason is the primary indication of what makes someone a ‘real’ human. This view would not grant Laura and Sesha, among many others, the status of ‘full person’ because they have a diminished capacity for reason, or at least one that’s harder to see. Such a view is for me both morally wrong and inaccurate. I’d argue that instead of basing human worth or personhood on reason, we should base it on a sense of common humanity of the sort that growing up with Laura taught me, as I described earlier.

An idea of common humanity could be based on lots of things, so we need to narrow the concept down. I think a secular version of it is the most inclusive: if I based it on the idea of an immortal soul, for example, this would alienate people who don’t think we possess such a thing. It is best therefore to base an idea of common humanity on something we can all agree on without controversy. Instead of the capacity for reason, I propose we base an idea of common humanity on the recognition of four distinct but overlapping concepts. If we recognise these aspects in someone, they then can be said to possess personhood and to belong to our moral community.

The first concept is the idea that we’re all members of the same species, Homo sapiens. This very fact gives us a moral obligation to treat other human beings with respect and compassion, if only because, beyond everything else, we share an ontological state, and a world, in common.

The second concept that emphasises our commonality is our shared capacity to experience suffering. The first of the famous Buddhist ‘Four Noble Truths’ is that experience is defined by dukkha which means ‘suffering or ‘dissatisfaction’ in Sanskrit and Pali. The fact that we all know what it is to face adversity or ‘suffer’ in some way, not only unites us, but can also provide us with a desire to assist others in their own times of need.

Related to this latter point is our third concept which, I suggest, is empathy: something that makes us human is the ability to empathise with other people – to psychologically put ourselves in the place of the other, to understand and share their suffering and happiness, and to imagine (as much as is possible) how it would feel to see the world from their perspective.

One thing needs to be added to address a possible objection to this idea. There are people with certain mental health issues that prevent them from showing, or having, empathy, meaning that they would be excluded on that basis. Yet psychopaths (for example), for all their problems, are human too. As I said, I wish to make the moral community as inclusive as I can, so the exclusion of anyone should be avoided if possible. Each of the four aspects can stand on its own merits as a suitable foundation for a common humanity, so the possession of all four is not entirely necessary as they overlap. Due to this, someone lacking just one of them for whatever reason should not be automatically excluded.

The fourth and final concept that should constitute a sense of shared humanity, is that all, or at least the vast majority of us, have the same basic wants and needs. For example, we all want to have a nice place to live; a nice family; we all like to be shown kindness and compassion, and dislike being treated with cruelty and hatred; and so on. Fundamentally, we all want the same things from life at a basic level. This is no less true for cognitively disabled people, mentally ill people, or anyone else.

These four concepts, taken together, would act as a decent foundation for a sense of common humanity, and so act as a much better indication of moral personhood than rationality, autonomy, and self-awareness. It should also be noted that these concepts could be expanded beyond ‘humanity’ to include many nonhuman animals who share with us many of the qualities I’ve outlined above. A sense of common humanity also aligns better with what most people view as a common-sense notion of what makes a human being. For example, when we see and hear of innocent people being killed in Gaza, Syria, or the Ukraine, and see the refugees, we often think we should do everything we can to help them. I think this is because we feel we share a sense of common humanity with them which extends beyond nation, race, ethnicity, and religion – and which is similar to how I think my sister viewed other people. My own sense of this is based on the four ideas I outlined above: Gazans, Syrians, and Ukrainians are of the same species as me; and I see them clearly suffering. As a result of these two facts, I can put myself in their place and imagine how terrible I would feel if I had lost family to war, was forced to flee my home, and had seen death and destruction close up. I also know that these people have fundamentally the same basic needs and wants as myself, and this obliges me to show kindness towards them as I would want it shown towards me if our situations were reversed. This is why I think common humanity can be applied to them and why they should be helped – I would believe such notions before I would even stop to think about their capacity for rational thought. Why would that matter in this context at all? Reason is extremely important for philosophy but we cannot live entirely according to reason, we must allow ourselves some capacity for (positive) emotion. It is based on such feelings (supported by rational reflection) upon which my idea of ‘common humanity’ is based and on which we should try to base any updated theories of moral consideration and personhood.

Many philosophers who discuss issues of moral personhood seem to have no experience of living with or caring for cognitively disabled people themselves. This criticism does not mean that I would forbid them from discussing it, or offering opinions on it that I may find controversial or even upsetting. That’s fine. However, I do think that a different, and perhaps more profound understanding of cognitive disability is gained by people like myself who have had a close family member with a cognitive disability. Such an understanding cannot be fully learned simply by reading about the subject; it’s simply a different form of knowledge. I think that if these thinkers had had similar experiences, they would realise that potentially excluding disabled people from the moral community based on the fact that they do not possess such qualities as reason, just sounds incomprehensible to people in my position. From my own experiences, Laura did indeed lack reason in a developed sense though she did at times demonstrate a capacity for it, however diminished. As I could not ask her, I cannot be certain. That said, the fact that she may not have had reason in the fullest sense was not important in the slightest. I never saw her as anything other than my sister and a fellow human being. She had so many other qualities that showed that she was just as entitled to claim a full sense of personhood as any non-disabled person. She showed a full range of emotions, a sense of who she was (showed explicitly by her love of looking at herself in mirrors), and an active form of verbal communication which included making certain noises to express certain feelings and to refer to certain people, (such as ‘Ma’ for our Mum and ‘brrr’ when she disliked something). She also had a love of music and nature, a fascination with animals, foods that she liked and disliked, the ability to learn, a genial personality, and so on. Indeed, there were many things she lacked, but those that she possessed leave me with no doubt that she not only had a life, but also a fully human experience, that was rich in its own way. I also know of plenty of other children similar to her.

My point is that, all this being said, to deny either her, or people like her (such as Eva Feder Kittay’s daughter Sesha) the title of ‘person’ or inclusion in our moral community because she could not use reason, or do things for herself, or did not possess some other such quality, itself seems irrational.

To conclude, to be the sibling of a disabled person – or indeed, the mother, father, or another family member – is a complex experience that carries with it both good, bad, and everything in between. However, I would not trade the positive qualities and experiences I gained by growing up with Laura for anything, and it was indeed a blessing to have had her as my sister. Philosophically, she showed me that the use of rationality cannot be the primary thing that defines someone as human. The very word ‘personhood’ demands that we include every ‘person’ within its boundaries, disabled or not – and that in order for us as philosophers to fulfil our obligations and make our discipline one that applies equally to all human beings, we need to start rethinking some of our most cherished concepts. Things change with time. To remain relevant to as many people as possible, so must philosophical ethics. After all, it is a branch of philosophy fundamentally concerned not with the self, but with the other.

© Dr Lee Clarke 2025

Lee Clarke is a philosopher who specializes in Buddhist Philosophy, Cross-Cultural Philosophy and the History of Ideas.