Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Tallis in Wonderland

Another Conversation with Martin Heidegger?

Raymond Tallis talks about communication problems.

A quarter of a century ago, I published A Conversation with Martin Heidegger (Palgrave, 2002). Though it was issued by a respected academic press, my book was a somewhat eccentric account of the central ideas in Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927), which is generally accepted as his magnum opus. My chapter headings say it all: ‘A Breath of Fresh Air’, ‘Wayfaring’, ‘Darkness in Todtnauberg’, ‘Leaving You and Not Quite Leaving You’, and ‘Sunlight on My Arm’. I also published a few after-ripples of this sustained immersion in Herr Professor’s thought, including The Enduring Legacy of Parmenides: Unthinkable Thought (Bloomsbury, 2007), which was in part prompted by reading Heidegger’s work on pre-Socratic philosophers. After that, the Magician of Messkirch largely disappeared from my intellectual life.

A year or so ago, prompted by an invitation to contribute to a collection marking the hundredth anniversary of Being and Time, I re-engaged with his writing. When I had finished the commissioned chapter, I found I was reluctant to abandon Heidegger again. There was unfinished business that seemed to be worth pursuing. Many subsequent hours spent arguing with his central ideas have generated two successive drafts of a book provisionally called Another Conversation with Martin Heidegger. As I embark on the third draft, however, it seems that the title has grown a question mark. I have rediscovered how Heidegger is one of the most exasperating philosophers to think with or against. And yet he cannot be ignored. He was, after all, arguably the most influential philosopher of the twentieth century. His nearest rival is Ludwig Wittgenstein, but the latter was in many respects an anti-philosopher. In the Preface to his only work published in his lifetime, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), Wittgenstein reported that he had found “on all essential points, the final solution of the problems” he had addressed in it, and then discovered “how little is achieved when these problems are solved.” Ouch.

No-one who takes philosophy seriously, therefore, can ignore or give up on Heidegger. If you decide to take the plunge, however, you have to face many obstacles. Because I expect that I will be devoting one or two of my columns in the next year or so to the fruits of my conversation with Heidegger, I would like to spell out some of these obstacles. Think of them as trigger warnings.

Warning: Heidegger Approaching

The first problem is Heidegger’s language. Even scholars who have devoted decades to studying his works admit that much of what Heidegger says remains unclear, ambiguous, or even contradictory. There are endless arguments as to the meaning of key Heideggerian terms such as ‘Being’ and ‘Dasein’ and how they do, or do not, connect with each other. Much of the (vast) secondary literature around Heidegger’s writing is consequently more like scriptural exegesis than critical evaluation of arguments and conclusions, which is apt because many scholars who comment on his work sometimes seem to do so from the standpoint of disciples rather than equals. But trying to understand the meaning of Heidegger’s prose through the interminable discussions as to what he means by certain terms he uses, and re-uses, can consequently seem to be a long digression from questions about the meaning of human life to questions about the meaning of Martin Heidegger.

The opacity of Heidegger’s texts is due in no small part to his fondness for neologisms or for putting existing terms to radically different uses. And this trait, evident throughout his writing, seemed to get worse with time. For instance, in Making Sense of Heidegger: A Paradigm Shift (2014), Thomas Sheehan, a brilliant Heidegger scholar, highlights a sentence in Heidegger’s Contributions to Philosophy (written a decade or so after Being and Time): “The cleavage is the unfolding unto itself of the intimacy of be-ing.” Sheehan comments that “Mae West could not have said it better.”

Then there is the massive scale of Heidegger’s oeuvre, lovingly curated by a vast army of scholars. When publication of the Gesamtausgabe (Collected Works) was completed, it comprised 102 volumes, amounting to 37,736 pages. One could be forgiven for thinking that Heidegger would unironically echo James Joyce, who reputedly said that “The demand I make of my reader is that he should devote his whole life to my works.” But those whose lives are otherwise busy with trivial matters such as employment, child-rearing, discharge of social responsibilities, political activity, making the world a better place, reading other philosophers, other writers, involvement in other cultural activities, etc, and who cannot avail themselves of a second incarnation, have sufficient time to be acquainted with only the acknowledged highlights, Being and Time of course being among them. Yet while Being and Time is acknowledged as his major work, for some commentators it has been superseded by subsequent writing. It goes without saying that others disagree. Normal readers can address the rest only via a small subset of the secondary literature (if at all). Hence the need to choose between struggling to understand the world and struggling to understand The Master. (The third possibility – advancing one’s understanding of the world through advancing one’s understanding of Heidegger – seems at times to be a forlorn hope.)

There is also the vast secondary literature. According to Academia.edu, 49,599 papers presently discuss ‘Philosophy of Martin Heidegger’. This disheartening statistic suggests that it is unlikely that my additional contribution to the literature – item number 49,600 – will settle disputes about Heidegger’s work and thus extract more Heideggerian light to cast on either the world we live in or the life we pass in it. At any rate, it will be in competition for attention with vast crowds of rivals saying, ‘Read me!’.

Ich Spreche Kein Deutsch

There is a third problem for those who, such as your columnist, cannot read German. Heidegger would have regarded this as entirely disqualifying us not only for commenting on his works but also for having any pretence to being a serious philosopher. He asserted that only two European languages were suitable for philosophical discourse – Greek and German (of course). But as he doesn’t offer much evidence for this extraordinary claim, I am not inclined to take it very seriously. Indeed, one would like to know how he could be sure that there is nothing to be learned from French or English philosophy. At any rate, it is surely rather odd that the accident of not being a German speaker should condemn one to not understanding the nature of human being, any more than being born before Heidegger shared his ideas with the world means one should be doomed to what he called ‘forgetfulness of Being’. We might also reflect that it was David Hume, writing in English, who awoke Immanuel Kant from his ‘dogmatic slumbers’, setting him on the path to the transcendental idealism which so heavily influenced Heidegger.

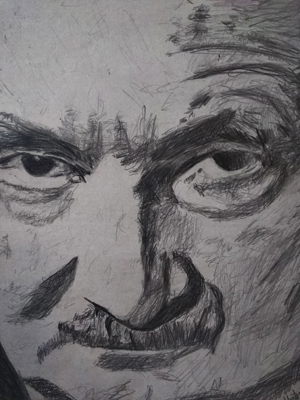

Martin Heidegger (detail) by Clint Van Inman

There is, however, a genuine barrier to his thought for those who cannot read German, which is well illustrated by the divergence between the two available English translations of Being and Time, the first by John McQuarrie and Edward Robinson, and the next by Joan Stambaugh (and subsequently revised): they have crucial differences in the rendering of key terms. And while many scholars feel that the McQuarrie and Robinson translation is more faithful to the spirit of the original, not all agree. Even his central term, ‘Dasein’ – meaning ‘being-there’, ‘being-in-the-world’, or ‘human being’ – is the focus of controversy among translators. In his revision of Stambaugh’s translation, Dennis Schmidt replaces ‘Dasein’ with ‘Da-sein’, defending the change on the basis of Heidegger’s own recommended revision for the Collected Works, even though Heidegger continued to write ‘Dasein’ himself. And the battle as to where, whether, or when ‘being’ should be ‘Being’ (with an upper case ‘B’), ‘being’ (with a lower case ‘b’) or even or ‘be-ing’, is equally drawn out. In German, unlike English, all nouns start with capital letters, so that doesn’t help.

If there are such barriers to reading Heidegger in English, then writing about him in a language which is, according to George Steiner “naively hostile to certain orders of abstruseness and metaphoric abstractions” (Heidegger, 1978) should be nigh impossible.

In response, I cannot help quoting the sixteenth century clergyman Ralph Lever (cited in Jonathan Rée’s wonderful Witcraft. The Invention of Philosophy in English):

“We… that devise understandable terms, compounded of true and auncient English words, do rather maintain and continue the antiquity of our mother tongue: than they that, with inkhorne termes doe change and corrupt the same, making a mingle mangle of their native speech, and not observing the properties thereof.”

A particular challenge presented by Heidegger’s vocabulary is that so many words seem to take in each other’s washing, and we never seem to touch base. A succession of terms occupies the favoured spot of being the most fundamental. The most conspicuous example of verbal jostling for priority is ‘Dasein’, but sooner or later, it gives way to ‘clearing’ or ‘uncoveredness’. Subsequently, that’s displaced by ‘appropriation’ or ‘Enowning’ as the source of both being and time.

It is of course possible to justify Heidegger’s distinctive use, or abuse, of language on the grounds that he was endeavouring throughout his long life to waken his readers, and indeed himself, out of modes of thought that had sedimented over 2,500 years, during which Western philosophical discourse had got too familiar with itself. Nevertheless, it is sometimes difficult to shake off the feeling that one is in the presence of a thinker circling round ideas that elude him; or of insights, visions, and revelations, almost extinguished rather than expressed by mighty helpings of verbiage.

Nevertheless

All this notwithstanding, there are, I believe, reasons other than vanity why I feel that Another Conversation with Martin Heidegger may be worth writing and (possibly) even reading, and why my reports from the battlefront may be justifiably shared with readers.

First, there is space for writers who are critical of Heidegger’s starting point, particularly as the critics (even ignoring the – usually Anglophone – scoffers who have not taken his ideas seriously) are vastly outnumbered by the exegetes. Radical dissent from Heidegger does not usually receive much in the way of attention, even in those relatively few cases where the critic subjects his texts to close reading.

Time for a confession: there was another prompt to my resuming engagement with Heidegger. When we moved house, we discovered the truth of Nietzsche’s observation that ‘we are possessed by our possessions’. My library was scattered and I lost my copy of Being and Time. I ordered another through Amazon (not something of which Herr Professor would have approved.) A couple of days after my order was delivered, I received a question from Amazon: ‘Did Being and Time meet your expectations?’ I think that question deserves an answer, not the least because seriously engaging with Heidegger forces one to dig deeper into the nature of philosophy, and, more importantly, of our world and the life we live in it.

Watch this space.

© Prof. Raymond Tallis 2025

Raymond Tallis’s Prague 22: A Philosopher Takes a Tram Through a City is out now in conjunction with Philosophy Now.