Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Philosophy of William Blake

Mark Vernon looks at the imaginative thinking of an imaginative artist.

The painter, poet, and engraver, William Blake (1757-1827) is not usually categorized as a philosopher, but I think otherwise. He engaged with the great thinkers of his day – particularly the three he regularly references as an intellectual triumvirate: Bacon, Newton, and Locke. Moreover, I reckon his ideas could be transformative now.

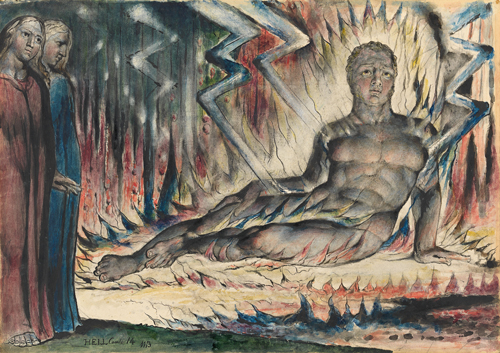

Self-portrait as Job – William Blake

Blake was born in Georgian England. The era was politically and socially tumultuous, witnessing Britain losing thirteen of its colonies in North America, developing its empire in India, and spending decades at war with France. During the same period men stopped wearing stockings in favour of trousers, and the words ‘nihilism’, ‘objective’, ‘regular’, and ‘history’ were either coined or took on the meanings they have now.

Shifts in language are a sign that much was happening philosophically as well. Blake knew the work of Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, and illustrated one of Erasmus’s protoevolutionary works, The Botanic Garden (1791). Evolutionary ideas were in the air, and empiricism was one of the watchwords of the times, alongside the phrase ‘trial and error’. Blake joined in with that spirit, being a great experimenter with materials. His workshop, in which he engraved, printed, and coloured with his wife Catherine, must have looked like a chemist’s laboratory – and smelt like one, too. Acids washing over metals left an arid tang in the air.

In the later years of Blake’s life, Humphrey Davey and Michael Faraday began experimenting on the phenomena of electromagnetism. Blake’s idea of contraries owes much to these emerging field theories; he suggested that life itself can be imagined as an energetic field held between opposing poles. Hence he wrote, “Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1793). The word ‘scientist’ still lay in the future, but Blake lived in the period during which the revolutionary potential of the new methodology Francis Bacon had outlined became clear. As yet, though, it was unclear what all these scientific investigations would amount to, and the thinking that would shape what became the modern scientific mentality was still widely contested. Jonathan Swift mocked the activities of the Royal Society (of scientists) in Gulliver’s Travels (1726), in which he imagined natural philosophers trying to extract sunbeams from cucumbers so as to warm the chill air of summer. Strikingly presciently, Swift also envisaged a great machine he called ‘The Engine’ – a mechanical monster that ejected streams of words, which people turned into essays and books without any need for effort or learning.

The Angel of Revelation William Blake 1804

Towering intellectual figures like John Locke and Isaac Newton were pivotal in developing a worldview that could contain the new intellectual developments – roughly speaking, a materialistic one. Locke called himself Newton’s ‘under-labourer’, borrowing his tools for investigating the physical world – experiment and observation – and applying them to psychology, epistemology, and politics.

Both Newton and Locke died in the early years of the eighteenth century, a generation or so before Blake, but the posthumous reputation of both was immense. Yet Blake was not only abreast of the latest developments and actively engaged with them in his work, he had fundamental criticisms of empiricism and its underlying materialism – criticisms I believe have well stood the test of time. In essence, he feared that the generalisations that Baconian investigations (that is, science) derive are so powerful that they come to be taken for reality itself. The result is a kind of distorted Platonism that holds ultimate reality to be mathematical: Unsurprising, since mathematics is an extraordinarily elegant tool for modelling reality, with entire groups of natural phenomena seemingly captured in, say, an equation as simple as Newton’s Second Law of Motion (F=ma). So the temptation to presume that nature is, at base, mathematical or mechanical becomes hard to resist. Further, the industrial, urban, agricultural and military technologies that were fundamentally reshaping Georgian life reflected the same order. They seemed to spring from a power to make things that wasn’t just a human capacity but reflected the very way of the cosmos itself. Technology was deemed God-given.

Blake sensed that a science of mere abstractions is on the way to becoming uncoupled from what it purports to study: “You accumulate Particulars, & murder by analyzing. But General Forms have their vitality in Particulars” he observed (Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, 1820). The upshot is ‘Generalizing Art & Science till Art & Science is lost.’ But are his concerns justified?

Perception

Take John Locke (1632-1704), the father of British empiricism. He taught that human beings interact with the world by receiving sense impressions that are formed into experiences (which he called ‘ideas’) by a limited imaginative capacity possessed by the mind, which is otherwise a tabula rasa or blank slate. In other words, humans navigate a pathway through life based on internal models, as opposed to directly participating in the world of which they are a part. Models of perception have adopted that basic approach almost universally ever since.

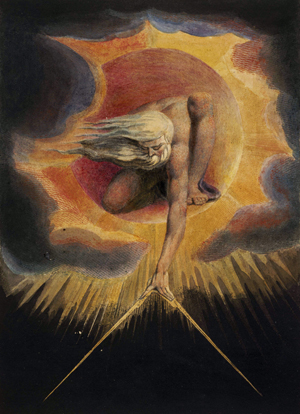

The Ancient of Days William Blake 1794

Blake fundamentally disagreed: “Man is Born Like a Garden ready Planted & Sown. This World is too poor to produce one Seed,” he argued (Annotations to Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Discourses, 1808). His point is that the mind is prolific in the way that a garden is prolific – not because it makes itself, but because it is part of a wider vitality that’s tended by a gardener. Blake was sure that human minds as blank slates is too poor a theory to account for the creativity that he knew within himself. Artists are receivers of inspiration and revelations with which they collaborate, whereas Lockean solipsism leads to what Blake calls “single vision and Newton’s sleep.” He was sure that human beings left to their own devices simply couldn’t devise buildings like Westminster Abbey or designs like Michelangelo’s. Locke’s closed-circuit model of the mind and the cosmos would lead to what he called ‘the same dull round’, devoid of genuine insight and novelty. And that isn’t right. Clearly human intelligence is self-transcending, Blake thought. That must arise from an imagination which is not a private possession but a sharing in a wider imaginative flow and intelligence active in all things.

Blake concluded that the empirical sciences massively understate the power and nature of the imagination. This capacity does not cast a light beamed out from skulls across an otherwise dark cosmos; rather, our imaginations share in a cosmic imagination that Blake thought divine. The natural world is shaped by this imagination, and so nature is the manifestation of imagination. The senses are only thresholds of perception: they’re not the limit of what we can perceive, but doorways through which we can perceive much more. Hence Blake’s probably best-known phrase: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern” (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790-93).

Another analogy Blake evoked was of looking through windows. No-one looks at a window apart from a glazier: we look through windows to the world they transmit. So, too, with the senses: do not say “I see with my eyes”, Blake insisted, but “I see through my eyes”. Sight then is, at once, a combination of the empirical and the imaginative. It doesn’t just record reality, like a camera, but participates with it. The task of a creative like Blake is to consciously align with the divine wellspring and awaken others to its presence: “They mock Inspiration & Vision. Inspiration & Vision was then, & now is, & I hope will always Remain, my Element, my Eternal Dwelling place; how can I then hear it Contemned without returning Scorn for Scorn?” (Annotations to Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Discourses, 1808).

Politics

Blake’s scorn was not only metaphysical, but also political. He spotted that Newton’s scientific revolution inspired political revolutionaries, such as Thomas Paine (1737-1809), as well as key figures in the establishment, not least King George III. Newton’s influence in the social domain rested on his portrayal of the natural world as orderly: governed by extraordinarily neat laws of cause and effect. The beauty of this regularity instilled a sense that society, too, should be beneficently patterned. That the universe could be thought of as akin to machinery inspired the progressive hope of transforming human governance – in other words, politics as social engineering. As Paine wrote: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand” (Common Sense, 1776).

Both sides in the tumultuous events of the era also wanted to claim divine authority for their cause – which to Blake was grounds for suspicion. For instance, the natural philosophy of Newton informed Paine’s deism (God as a distant cosmic engineer). Blake loathed this theology, as, for him, God is a living presence and spirit: “I am in you, you in me, mutual in love divine,” he has Jesus say in his poem Jerusalem: the Emanation of the Giant Albion (1820). On the other side, George III felt that cosmic regularity justified his authority: “God and the Georges were the constitutional monarchs respectively of the universe and the nation” explains the historian Roy Porter (Enlightenment: Britain and the Creation of the Modern World, 2000). The royal gardens at Richmond celebrated this lawful rule by featuring busts of Newton and Locke inscribed as ‘the Glory of their Country’, thereby corralled to the King’s cause.

William Blake by Thomas Phillips 1807

Blake, Hume, & Newton

Blake was on neither side, but nonetheless, had allies. Take David Hume (1711-1776). A luxury edition of the Scot’s bestselling History of England (1754) – which was better known than his philosophy during his lifetime – was to have included engravings by Blake, though that project was scrapped. But whilst when it came to philosophy, Hume’s sceptical agnosticism would have put him at odds with Blake, they would have found sympathy in Hume’s critique of the new sciences. Hume had pointed out that whilst it is possible to accumulate evidence for the observed properties of things, this data could only lead to universal laws if nature were assumed to operate by the same laws everywhere. Only then could a string of similar cases lead to a general conclusion. However, that uniformitarianism, as it’s called, can only ever be an assumption, since human beings lack the omniscience to check everything everywhere.

Hume concluded therefore that scientific knowledge rests on an act of faith, or, at best, a custom of presuming that the way things are today, in one place, is a good indicator of the way they will be tomorrow, in another place. That assumption works until it doesn’t. Hume therefore formulated a challenge to the reputation of science as a fully justified path to knowledge – a challenge with which philosophers still grapple. To some of the more non-philosophical scientists the argument seems like nitpicking, as if it’s trying to undermine the great discoveries of physics, chemistry, and biology. It’s not really. It’s rather questioning how far generalisations can take us, and asking what blind spots are introduced in the process.

This chimes with Blake’s wariness of generalisations. Blake was sure that nature isn’t uniform; you only have to take a look. Blake loved nature’s diversity much, and detected a love of tyranny and a passion for revolutionary fervour in the assumption that there should be universal principles governing all. He insisted, “One Law for the Lion & Ox is Oppression” – thereby linking the poetical and the political. (Laws never have positive connotations for Blake. They are ‘stony’, ‘self-righteous’, ‘cruel’, ‘binding’, and ‘abstract’, because dehumanising. He also writes of ‘howling victims of Law’.)

Another supporter Blake could have welcomed is less expected: Isaac Newton himself. The hero of Baconian science was explicit that generalisations such as natural forces, as well as quantities such as mass and inertia, may be useful, but are only postulations: “You speak of gravity as being essential & inherent in matter, pray do not ascribe that notion to me, for ye cause of gravity is what I do not pretend to know,” he stated (Letter to Richard Bentley, 1693). Recent research has suggested that Newton’s theory of gravity as a force acting at a distance was inspired by his esoteric studies. Newton devoted much of his time to investigating ancient beliefs in daemons, for example – entities which, according to Plato and his followers, mediate cosmic attractions and connections. The link was a natural one for Newton to make, as it was for many at the time. Moreover, as Newton’s proposals about the dynamics of the heavens became known, they sparked a fashion for astrology. Which is all about how celestial entities supposedly act at a distance to influence human bodies on Earth.

Blake was not against science. Rather he longed for ‘sweet Science’, as he called it – a mode of knowledge pursuit that is in happy dialogue with the imagination. He was sure that rather than amplifying our perceptions, putting experiences to the test as the basis for knowledge would generate a culture of scepticism, fear, and nihilism: “If the Sun & Moon should doubt, They’d immediately Go out” he jeered.

Indeed, Blake can be placed in a line of scientists inspired by the Romantic tradition. The best known of these is Albert Einstein, who reckoned that the imagination is given to us precisely to convey the ways of the cosmos. Einstein knew how to combine fantastical imaginative journeys, such as travelling on light beams, with theoretical rigour: he produced the Theory of Special Relativity as a result of that playful trip of the imagination.

Today the Romantic impulse and Blake’s way of expressing it might be a help as science increasingly leans on algorithms and data. Science needs insights, not just results. Blake the philosopher can build the trust needed to see not with computers, but through them.

© Dr Mark Vernon 2025

Mark Vernon is a psychotherapist, a writer, and a Philosopher in Residence at Broughton Sanctuary. His new book Awake!: William Blake and the Power of the Imagination is out now. Please visit markvernon.com.