Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Heideggerian Disruptions of Zippy The Pinhead

Ellen Grabiner ponders the bearable lightness of being a Pinhead.

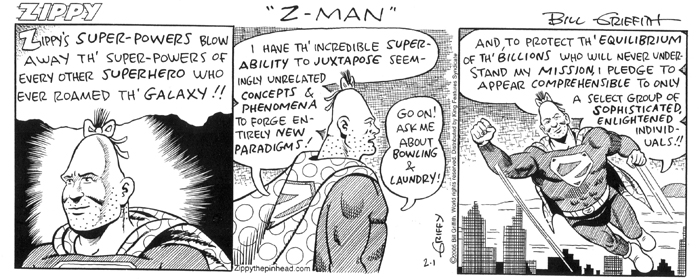

In the recently-surfaced spate of anthologies, books, and magazine articles which have spotlighted the phenomenon of the superhero, there has been one egregious omission. There is nary a mention of Z-Man, alter ego of Zippy the Pinhead, creation of Bill Griffith, who has pledged to “appear comprehensible to only a select group of sophisticated, enlightened individuals.” To rectify this perhaps understandable omission, I would like to put Zippy front and center. Paying homage to the Z-man’s super ability, I risk offering a super juxtaposition of my own: Martin Heidegger and Zippy the Pinhead. These thinkers both question our habitual approaches to everyday life and suggest we abandon gestellen – the ways in which we tend to ‘enframe’, and consequently diminish, our experience.

All Zippy cartoons © Bill Griffith. Please visit zippythepinhead.com.

Encountering Heidegger

When I first tried to read Heidegger, I was in the thick of a doctoral program, investigating what I perceived to be the rampant hostility directed in Western thought at visual paradigms. As a long-time visual artist, I took umbrage. I was desperately seeking something in support of visual experience that was enriching and opening, instead of the ubiquitous objectifying gaze. When I stumbled upon Heidegger’s, The Age of the World Picture (1938), I jumped to what I thought was the obvious conclusion: finally, here was someone who was extolling the virtue of picturing. I approached his essay with that expectation in mind. I was so sure of what I would find in his essay that even as I was reading it I was blinded to the actual words Heidegger had written – blinded to the fact that he was not lauding but bemoaning the modernist tendency to ‘picture’. As I read, I had the strangest sensation of swimming against the tide. While Heidegger has been accused of many things – being reactionary in his attitude towards technology, being a Nazi sympathizer – as far as I am aware, he has never been accused of being easy to read. And if, like me, you don’t read German, you’re reading a translation, for starters. But reading Heidegger believing he is saying one thing when in fact he is saying quite another, was an impossible experience.

As I read, I became aware that my forehead was scrunched up with effort. I was working incredibly hard and understanding almost nothing at all. I was tempted to throw my hands up and say uncle. At those moments, in an effort to calm myself, I would think, just read this as poetry – or perhaps as Heidegger might have encouraged, as language. Just let the words wash over you, I would coach myself. Don’t try to understand him in a linear, rational way. And doing so, suddenly, remarkably, meaning would take shape. Whether it was Heidegger’s intended meaning, even a meaning a Heideggerian scholar might attribute to him, I can’t know. But as I read phrases that, when approached logically, seemed close to gibberish – ‘The nothing nothings,’ [Das nicht nichtet] ‘The World worlds’ [Der Welt weltet], ‘Language is the house of Being,’ ‘the soundless echo’ – suddenly these phrases resonated – not in a precise, linear, rational way, not even in a way I could articulate, but in a tacitly visceral way. In reading these words, I was forced to suspend what I already knew. In fact, I was forced to reconsider knowing itself; forced to rethink how I was approaching Heidegger; forced by the deliberate oddness of his words to stop trying to understand them in the usual ‘everyday’ way, and let the meaning show itself to me. I now believe that Heidegger’s excessively particular use of language was rooted in a hope that his out-of-the-ordinary constructions would cause us to stop and abandon our everyday, habitual way of reading – abandon the imposition of what we already know so that his meaning could be uncovered.

Loving the Box

In Being and Time (1927), Heidegger examines what he calls our everydayness. He suggests that by discovering how we are, every day, we will prepare the way towards understanding Being: “By looking at the fundamental constitution of the everydayness of Dasein [personal experience] we shall bring out in a preparatory way the Being of this being.” Whatever you may think about Heidegger, this disruption of our habitual, everyday tendency to short-cut our understanding of our experience was his legacy. And none has taken up the mantel of Heideggerian disruption with as much verve as Bill Griffith’s Zippy the Pinhead. Like Heidegger, Zippy confuses, disrupts, redirects and returns us to our everydayness so that we might see it anew.

To appreciate Zippy, it is necessary to understand the context in which he lives. As Heidegger will insist that you can’t know the hammer without knowing the wood, the nail, the heft of the hammer’s weight as you lift it in the air, the gravity that pulls it down, so we can’t know Zippy unless we know the panel: the box in which he lives (and which he reveres); the gutter around it which places him in and out of time; the speech or thought bubbles in which his utterances reside; and the worlds of high art and pop culture, which, in juxtaposition, afford Zippy a mechanism for upending our notions about comics, and lead us to Zippy’s deep, philosophical truths.

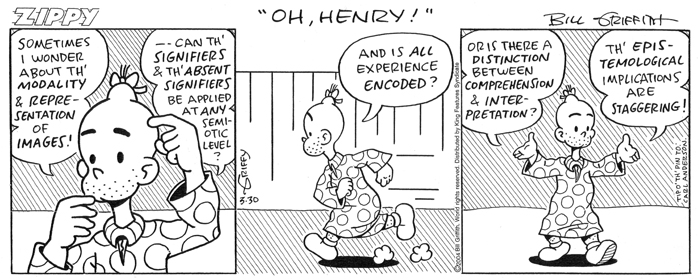

Whether we choose to admit it or not, our approach to comics is also generally, as Heidegger would say, gestellen, or ‘enframed’. Our expectation of the funnies is for them to be just that. Zippy is sometimes side-splittingly funny. But when we approach Zippy expecting “the usual ‘set-up and pay-off’ type of gag humor” we will be sorely disappointed, as Griffy, Bill Griffith’s comic alter ego and Zippy’s foil warns. And in much the same way that Heidegger returned again and again to the roots of Western philosophy in Greek thought, Zippy returns to his own personal foundation in the roots of the comic art of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy and Sluggo, and in Carl Anderson’s classic comic strip Henry. These are what might come to mind when we think of the quintessential ‘comic’. In Henry we find a narrative flow and the utilization of pantomimed, comic gestures: Henry strolls casually, hands clasped behind his back, runs, kicking up conventional cloud puffs, expresses the narrowness of his escape by wiping his sweating brow. If, however, we were to approach Zippy expecting this, thinking that we already know what a comic is, we will be pulled out of our complacency in a way reminiscent of my reaction to Heidegger’s Age of the World Picture.

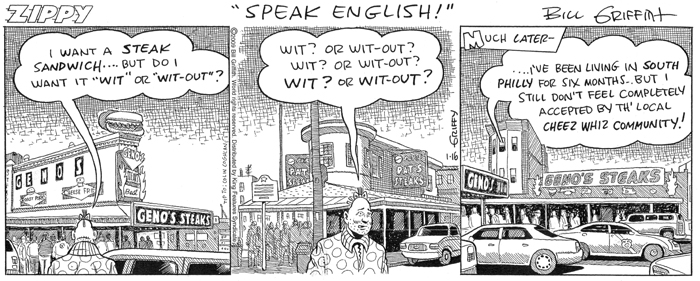

Like Heidegger, Zippy is a big fan of seeing and saying; and like Heidegger he uses language as language, to help up-end our expectations of the comic narrative. By highlighting oversized landmarks, the ubiquitous diner, the meditative sport of bowling, or the transcendent laundromat, he brings us right into the moment. Griffith’s jarring juxtaposition of high culture and kitsch brings into focus what we overlook in our everyday way of being, and defines Zippy’s cultural critique, zealously engaging ideas that have provoked throughout the ages as well as those endemic to our post-postmodern lives. Even Zippy’s essential self is a comment on identity politics. The pinhead with a bowed top-knot, a perennial five o’clock shadow, dressed in a polka-dotted muu-muu [smock], makes a statement by his very being.

Pinheads, Stone Heads and Eggheads

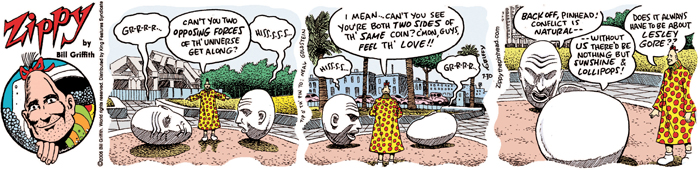

To elucidate the Pinhead’s thinking I’d like to zoom in. Like Heidegger, through Zippy and his pal Griffy, Bill Griffith is no stranger to the big questions: from aesthetics to existentialism, to the on-going, non-linear, exploration of our dualistic nature. Like Heidegger, Zippy has made it his mission nothing less daunting than to undo the Cartesian project of fully rationalizing knowledge. But while Heidegger emphasized the strife entailed in Being, Zippy’s approach might be considered closer to Gadamer’s idea of ‘play’. At times, Zippy simply provides us with a randomly absurd juxtaposition: his is a loud, persistent, and silly voice cheerfully yelling about what is huge and absurd in our culture, and what we don’t ever really see as we walk, heads down, absorbed in our thoughts and comfortable in our knowledge of what is all around us. At other times he tackles the notion of duality head on. Below is an example of both.

When Bill Griffith wants to give form to the opposing forces of the universe, he chooses something monolithic, something we couldn’t possibly overlook: enormous stone head sculptures. And by engaging them in conversation, Zippy renders them visible. Could he be characterizing these opposing forces as rigid? Blockheads? Petrified? Could he be commenting on the mind/body split? With Zippy/Griffith, we never know for sure. The stone heads, not co-incidentally, are modeled from Robert Arneson’s sculptures in the Embarcadero in San Francisco, and the piece is called Yin and Yang, part of the Egghead series. Arneson’s stone heads stand for the intellectual intercourse of academia; but for Zippy, stone heads signify our ingrained expectation that all encounters between concepts will at the very least result in them being organised hierarchically, and more likely, be adversarial. The opposing forces insist that to be anything other than at each other’s throats is ‘unnatural’, while on the other hand Zippy the Pinhead conforms to no one’s preconceptions: he embodies a random spontaneity and delight in all things, from the mundane to the sublime. The huge rolling heads are just one more example of the foils who resist Zippy’s attempt to mediate. I would be remiss here if I didn’t point to the paradoxical questions raised by the nature of Zippy’s intervention. Zippy, in arguing for an alternative to the adversarial approach of the heads, is in conflict with them, and by virtue of his plea, posits an ‘either’ to their ‘or’. Of course, this is one layer of what makes the comic ironic and funny. But does it in fact prove the heads are ultimately correct? Is conflict not only natural, but inevitable? In Zippy’s world the strange intermingle, fraternize in ways that undo their polarization. Zippy reframes the stone head hostility, so that each head is merely the flip side of the other. They are connected, bound to one another. And in this case, Lesley Gore provides the unexpected swerve of non sequitur which marks Zippy’s discourse.

Zippy the Metacomic

By articulating and decoding the nature of comics in general, Zippy the Pinhead often functions as a metacomic: a comic that calls attention to the comic itself. This self-reflective thread runs through many of Bill Griffith’s daily syndicated strips, but there are several strips in which this is addressed explicitly. Above Griffith appropriates Henry for just this purpose. In fact the simplicity of Henry’s conventional comic gestures is the perfect ‘grrr’ to the ‘hiss’ of some hefty questions: What is the nature of representation? Is all experience encoded? How do we know what we think we know? Transforming Henry into a mini-pinhead, Griffith asks questions that are in part serious and important, and in part making fun of those of us who actually do ask these questions (and even think that turning to comic strips like Zippy can give us answers), and at those who create the comic strips in which they are asked. Here we find irony combined with ridicule.

The Pod of Being

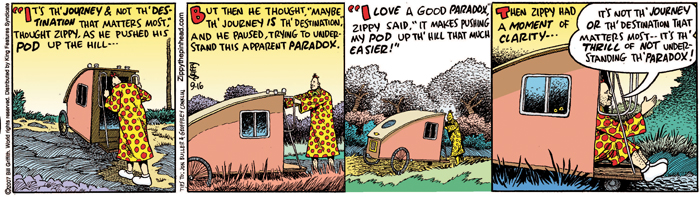

Following in Heidegger’s footsteps, Zippy appreciates that it’s about the journey, not the destination. As he pushes his pod up a hill, he considers: “Maybe th’ journey is th’ destination.” Like Heidegger’s ‘soundless echo’, Zippy loves a good paradox, especially when he doesn’t understand it. However, his confusion doesn’t keep him from philosophizing or waxing pithy. Pontificating about internet addiction, art, video gaming, advertising, Google, or skeeball, language is for Zippy the house of Being, as it was for Heidegger. Or maybe for Zippy, it is more accurately the pod of Being. But in this age of instant, more, faster, better, it is heartening to know there is a superhero among us whose super juxtapositions bring us up short, undo our enframed expectations, then reliably return us to our everydayness and our experience of the present moment.

© Ellen Grabiner 2011

Ellen Grabiner teaches Cinema and Media Studies at Simmons College, Boston, and is working on a book on Avatar, due out next year.

Bill Griffith

Bill Griffith is the creator of Zippy the Pinhead. Ellen Grabiner asks him about his philosophy.

One of my interests is what the artist brings to the practice of philosophy. Can you comment?

A lot of great comic strips have engaged in philosophy, if one defines philosophy as the pursuit of wisdom, or as a critical analysis of beliefs. Charles Schulz’s Peanuts and George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, Walt Kelly’s Pogo, and even ‘naive’ strips, like Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy, dabble in philosophy. Comics present an alternative reality, a parallel world brought to life by the cartoonist. I try to present a cohesive worldview in Zippy, if only through the cumulative effect of so many years of strips. It’s as much psychology as it is philosophy. I’m not always happy, but Zippy is. What does that say about me? I like to think that Zippy’s ‘craziness’ keeps me sane. And who is Mr Toad? My angry father? Is Shelf-Life the guiltless go-getter I was supposed to be? Am I exorcising these various demons inside me through my daily comic strip?

I guess I straddle the boundary between what is expected and what is possible. I ask my readers to meet me halfway. For me, comics are personal. Just as I rejected the corporate world, I reject the idea that a comic strip is there to deliver a punch-line and fade out.

Do you think of yourself as a postmodernist?

Having made the transition from ‘high’ art to ‘low’ art myself, from my unsuccessful career as a painter in New York to Underground cartoonist, to a syndicated cartoonist, the blurring of that arbitrary boundary line is something I think I’ve come to embody. The whole idea of a cultural gatekeeper seems archaic to me at this point. You’re either smart or you’re not, and, therefore, your work is either smart or it’s not. Smart and dumb are the only distinctions I apply to art of any kind. And that isn’t to say ‘dumb’ art or comics, don’t have value. Some of the best comics were made by naive or business-like artists for strictly commercial considerations, like Nancy (Ernie Bushmiller), Gasoline Alley (Frank King), Dick Tracy (Chester Gould) or Mad magazine (Will Elder).

Playing with the permeable barrier between ‘intellectual’ and ‘entertaining’ comics is a lot of fun. I’m happiest when I’m making juxtapositions that work, that lead to a satirical or simply interesting place. When Zippy says, “All life is a blur of Republicans and meat,” the intention is high-minded (“All life is…”), but the disconcerting word-picture of a right-wing politician with a raw steak is, I hope, both funny and illuminating.

Do you surprise yourself drawing a strip?

I constantly surprise myself with what I draw from panel to panel. It can feel a little like doing acrobatics without a net. I apply the same approach to drawing as I do to juxtaposing thoughts. I like the writing to carry you coherently from one thought to the next, while the drawings play with time and space. Often, I look through old magazines to get started. I’ll see a grouping of figures that triggers some kind of story-line or playlet, and go with it to see where it will lead. I rarely come to a dead end.

Are you still having fun?

As long as I’m allowed to do Zippy every day with no editorial control whatever and my commute is fifty feet from my house to my studio, I’m having fun.