Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Paolo Sarpi (1552-1623)

Gerald Curzon reviews the life and opinions of the original New Atheist.

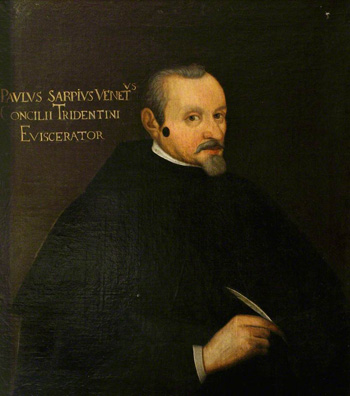

Paolo Sarpi, the first philosopher to develop systematic arguments for atheism, is now hardly known except by historians of ideas. Once he was famed throughout Europe. John Donne kept his portrait in his study. Boswell called him a genius. Both Gibbon and Macaulay praised him. He was well ahead of his time, since it was not until half a century after he died that Matthias Knutzen, the first widely mentioned atheist in modern history, distributed three handwritten atheist pamphlets at Jena in 1674.

Recent onslaughts on belief in God by Dawkins, Dennett, Harris, Hitchens et al have made atheism quite acceptable. However, for many centuries, atheism would have been expressed with extreme caution. Sarpi was a monk of the Servite order, and at a time when heretics were burnt at the stake, a secret atheist.

He was born in 1552, the same year as his antagonist, Pope Paul V, and was the leading Italian intellectual of his age. Sir Henry Wotton, the English ambassador to the Venetian Republic, called him “the most deep and general scholar of the world” and “a sound Protestant as yet in the habit of a friar.” He was a life-long sceptic who lived in many worlds – the worlds of Catholic monks, Venetian patriots, and European radicals. He called himself “a chameleon [who] had to wear a mask like everyone else in Italy.” And in fact, what he really believed only became public long after he died in 1623.

Sarpi’s biography, written by his admiring friend and fellow monk Fulgenzio Micanzio, said that even as a child he was outstandingly serious and studious. He was a polymath with a photographic memory. Micanzio said “If he read a book – he knew all and could remember the very Leaf where he had observed any thing.” On meeting him, experts often assumed their speciality was his own main interest. He was involved in many scientific advances, including Galileo’s development of his telescope and his researches on sunspots. He also contributed to understanding the circulation of the blood. Wotton called him “a rare mathematician, even in the most abstruse parts thereof – and yet withal so expert in the history of plants as if he had never perused any book but nature.” At eighteen, after a brilliant display of learning, he was made Theologian to the Court of Mantua, and then became professor of philosophy at the Servite convent at Venice. At twenty-six, he was the youngest Provincial in the three hundred year history of the Servite Order. At thirty-five, he was given the second highest post of the Order at Rome, but left three years later in disgust, saying, “only ruffians, charlatans and other devotees of pleasure and profit flourished there.”

Sarpi’s Opinions On Religion

Sarpi returned to his monastery in Venice, where he spent the years from 1588 to 1591 writing his Pensieri Filosofici (Philosophical Thoughts), his secret notes on religion. These were only published in complete form together with his other Pensieri in 1976. They reveal his unremitting antagonism to the Church. They also reveal him as an atheist in the modern sense of the term, not as the term was understood in his time – as someone who pursues pleasure and power without fear of divine retribution.

In Paolo Sarpi: Between Renaissance and Enlightenment (1983), David Wootton wrote that until recently it was believed that in Sarpi’s time it was almost impossible to follow atheism as a philosophy because “the very concepts and assumptions necessary for systematic unbelief were lacking.” However, taking an essentially materialistic point of view, Sarpi painstakingly formulated a systematic basis for atheism.

The Pensieri stated that knowledge is based not on divine revelation but on evidence obtained through the senses. Sarpi believed that reason, when based on the perceptions of the senses, was the best kind of philosophy “that in this poor life we can hope to have.” Moreover, the Pensieri declared that “the end of man as of any other living creature is to live”; that belief in God sprang from ignorance and the desire to escape reality; and that while religion might have social value, this did not require a fear of Hellfire. Sarpi rejected all arguments for the existence of God, and believed that everything had a natural cause due to an inevitable chain of circumstances and the basic laws of nature. He also believed there were no miracles, that nothing had a supernatural origin, and that faith was an illusion. This philosophy saw belief in God as a dream based on desire for a being who was not restricted by the laws of nature.

Sarpi saw the State as necessary, since it made society possible but religion was only useful insofar as it supported the institutions of the State, and should therefore be under State control. In the State versus Church controversies that often flared up, he invariably supported the State. As for the Church, it was the instrument of a powerful group that used it for their own ends. He followed the Muslim philosopher Averroes (1126-1198) in seeing religion as, at best, a myth that may be necessary to ensure good behaviour by those who were incapable of reason – that is by those who were incapable of understanding philosophical truths. Nevertheless, Sarpi believed that human powers of reason had intrinsic limitations, and perhaps surprisingly, that book learning was mainly valuable as a source of intellectual pleasure. He was familiar with the work of another sceptical philosopher, Montaigne (1533-1592), who had the question ‘What do I know?’ carved above the fireplace of his study, and wrote “knowledge can be a burden.” Similarly, Sarpi wrote that the illusion of knowledge was a major source of misery.

Sarpi’s ideas were highly original – almost astoundingly so – and he developed them when there were few people with whom he would have dared to discuss them. Promoting atheism or other unorthodox religious ideas was extremely dangerous. Campanella (1568-1639), who proposed that the study of the world should be based not on faith but on experience, was tortured on the rack and imprisoned for decades. Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) who contradicted several doctrines of the Church, was burnt at the stake.

Francis Bacon’s Great Instauration, published in 1620, three years before the death of Sarpi, described a philosophy of scientific discovery that was consistent with the Pensieri, and it is significant that Sarpi and Bacon were in correspondence since 1616. Like Galileo, whom he often met in Venice, Sarpi believed that knowledge came about principally not by philosophical deduction but by induction, that is by observation and experiment. This approach may now seem self-evident, but in Sarpi’s day many learned people thought otherwise and could not accept findings if they went against their deductions. For example, since the moons of Jupiter as shown by Galileo’s telescope contradicted the Catholic church’s concept of the divine perfection of the universe, the astronomer Francesco Sizzi believed that they could not exist and refused to use the telescope to view them. Sizzi was not a fool, but he was imprisoned in his ‘mind-forged manacles’.

Three centuries after Sarpi’s death, Frances Yates pointed out that Sarpi’s new attitude to religion, Palladio’s new architecture, and Galileo’s new science, were all aspects of a single approach to the world, a renaissance in thought.

The Interdict Crisis

Until the Interdict crisis of 1605 between Venice and Rome, Sarpi was almost unknown outside Italy. His opposition to the Church then spread his fame throughout Europe.

The causes of the crisis included serious losses of revenue to Venice as its numerous clerics were avoiding taxation, and pious citizens were leaving more and more of their property to the Church. Also, the important Venetian book trade was facing ruin, as the new Pope Paul V was trying to crush any signs of intellectual independence by banning any books that remotely questioned Catholic doctrine. The crisis peaked in autumn 1605 when Venice imprisoned two priests. Rome claimed that only she had the right to try clerics, but Venice did not hand them over. An Interdict of excommunication was then imposed on the city. Advised by Sarpi, Venice ignored it, arguing that the State had authority over secular crimes even when they were committed by clerics. A Europe-wide controversy ensued and war threatened until a face-saving agreement was made and the imprisoned clerics were quietly handed over to Rome.

Paolo Sarpi, with patch

Paul V never forgave Sarpi for flouting his authority. He invited him to Rome for ‘discussions’, but Sarpi declined. This was prudent, since after being invited there another Venetian opponent of Rome, Fulgenzio Manfredi, was hanged for heresy and burnt in the Campo di Fiori. In Venice, a gang, almost certainly acting with Pope Paul’s approval, attacked Sarpi with stiletto daggers. The black patch covering the resultant scar on his cheek can be seen in his portrait at the Bodleian Library.

The History of the Council of Trent

Sarpi’s atheism was confirmed in 1619 by his anti-Papal History of the Council of Trent, one the greatest historical works of the age. A principal aim of the Council of Trent was to oppose the growing schism between Rome and the Protestant Churches. It claimed to give the Protestants a fair hearing, but it was heavily weighted against them as they were not allowed to vote, and they were not given any important concessions. Sarpi’s History exposed how the meetings were stage-managed, with many abuses left unreformed, and the schism left unhealed. Rome tried to stop distribution of the History by putting it on the Index of censored books. However, the Archbishop of Canterbury sent an eminent scholar to Italy to persuade Sarpi to allow it to be printed in England. The manuscript was smuggled out of Italy by Dutch merchants in weekly packets labelled canzoni (music scores), with the author’s name on the title page lightly disguised as ‘Pietro Soave Polano’, a near anagram of Paolo Sarpi Veneto.

Sarpi was becoming more and more alienated from Rome. Not only had he supported Venice in the Interdict crisis and defied Rome by publishing a book that was put on the Index, even worse, it had been edited by Marc Antonio de Dominis, who was in even worse odour at Rome than Sarpi. De Dominis was a notorious turncoat who, after being Catholic Bishop of Spalato (now Split), had left the Church of Rome and had been made Anglican Dean of Windsor before returning to Catholicism and dying while in the hands of the Inquisition. The flamboyant De Dominis had, without Sarpi’s permission, added a long, violently antipapal subtitle to the History, infuriating the Pope, but also distressing the sober and cautious Sarpi.

Sarpi’s Death: Different Tales

Sarpi died in 1623, aged 71, still behind his masks after surviving more than one investigation by the Inquisition. Micanzio, who was with him at the end, wrote two accounts of his death. One, sent privately to an English friend, contained no specifically Christian phrases. The other, written for public consumption, said he had observed the last rites of the Catholic Church, receiving the sacraments and meditating on the crucifixion. It also mentioned rumours that he died “crying out with apparitions of black dogs – and hideous noises.” Both Micanzio’s and Henry Wotton’s accounts of Sarpi’s funeral refer to the numerous solemn mourners. However, the Vatican-approved historian Pastor wrote that “many walked but reluctantly.”

After Sarpi died, the Church continued to attack him, and tried to obliterate his memory. Michael Branthwaite, an English agent in Venice in the 1630s, wrote that the Church burned his effigy in Rome and wanted to have his body dug up and thrown to the dogs, but Venice refused to disturb his grave. Not until 1898 was permission given for his statue to be erected in Venice near the site of his former monastery.

© Prof. Gerald Curzon 2014

Gerald Curzon is a retired professor of neurochemistry (University College, London) with a life-long interest in history. He first heard of Paolo Sarpi while preparing Wotton and His Worlds: Spying, Science and Venetian Intrigues (Xlibris, 2004).