Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

A Justification of Empirical Thinking

Arnold Zuboff tells us why we should believe our senses.

How can you know that your present experience isn’t due to an artificial stimulation of your brain disembodied in a vat, or to a merely chance and causeless occurrence of its pattern in the absence of any world outside it? Either of these possibilities, or numerous others we could imagine, would involve exactly the consciousness you’re having at this moment: these possibilities and what you think to be your actual situation in the world are completely indistinguishable from within this conscious experience. So what could legitimately count in favour of the sort of thing that you do think about the world – that it exists beyond your experience? How, with any justification, can your thinking reach beyond the appearances that would be common to all these skeptical hypotheses?

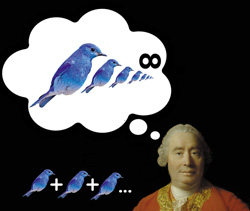

Before we directly confront skepticism regarding the world external to appearances, it will be instructive for us first to take up David Hume’s famous challenge to provide a rigorous justification for induction. ‘Induction’ is forming beliefs concerning repeatedly observed associations of qualities or things, that those associations will continue into the future.

Hume’s Challenge

Let me try to evoke for you Hume’s classic ‘problem of induction’. On a newly discovered island we have so far observed 100 birds of the new species ‘humebird’. Every one of these humebirds has been blue. After that many such observations, we come to expect very confidently that the next new humebird we observe will also be blue. But is there any rational justification for this expectation?

Here is what Hume would have said about this case: it is impossible for us to demonstrate a priori – that is, through mere examination of the concepts involved in the formulation of the thought – that it is logically necessary that the next humebird be blue, in the way that it is logically necessary, for instance, that 2 plus 3 be 5.

Hume’s method of induction

We are indeed rationally justified in thinking 2 plus 3 will always be 5, because 2 plus 3 is not distinct from but rather identical with 5. Therefore we can know that denying this claim – trying to think instead of 2 plus 3 as not 5 – brings us into the impossible mess of a contradiction. We can thus be rationally justified in our confidence that there will be no cases of 2 added to 3 that produce anything other than 5.

In contrast to this, however, the next observation of a humebird must be distinct from all preceding observations, and blue is distinct from the other humebird qualities, so it is impossible to discover just in the concepts involved that there is any contradiction in the next humebird being some colour other than blue.

Hume gave up any hope for intellectually justifying the enormously important employment of induction. He was thrown back on seeing induction as an instinctive development of habits of expectation arising out of repeated experiences of logically-unnecessary combinations of properties, such as the other properties of the humebird with blue: we see numerous blue humebirds, and it is simply in our nature to come to expect that the future will resemble the past – that the next humebird will also be blue.

Why Hume Is Wrong

I think Hume’s skepticism regarding the reliability of induction is wrong. There is indeed, as Hume insisted, no logical necessity that the next humebird will be blue; but there is a logical necessity that it is probable that the next humebird will be blue, given the evidence so far, for it is necessarily probable that the collection of random samples you have observed has a similar proportion of blueness to that of the general population from which it has been taken.

Let me explain.

I think that while observing the 100 humebirds, rather than forming a Humean ‘habit of expectation’, we are implicitly calculating the most probable hypothesis concerning the general population of humebirds from which the observed birds are being randomly sampled. The hypothesis regarding this population that we justifiably come to favour as most probable is the one that would make the occurrence of the evidence – our observations – the most probable occurrence. We are justified in favouring this most probable hypothesis since the high probability of the evidence given that hypothesis necessarily lends its weight to the probability of the hypothesis itself.

This last idea is quite complex, so please allow me to elucidate it. It may help us to consider an example of a hypothesis that we would justifiably reject as improbable given the evidence. The most improbable of such hypotheses would be the hypothesis that the only birds that are blue among our population of humebirds happened to be the 100 that we have already seen. If that hypothesis were true, then it would have been highly probable that non-blue birds would have got mixed into the first hundred observations, and our actual observations of only blue humebirds would have had to have been an extremely improbable event. But something improbable necessarily has a low probability of occurring. Hence the improbability of the evidence given this hypothesis makes this hypothesis, when combined with the evidence, necessarily improbable. By contrast, the observation of nothing but blue humebirds gets less and less improbable as our hypotheses increase the proportion of humebirds among the general population that are blue; and the least improbable hypothesis after 100 observations is that humebirds are generally blue. So that is the hypothesis we implicitly settle on as most probable. It goes along with this hypothesis, of course, that the next humebird to be sampled from the same population (and under the same general conditions) will be expected to be blue. This, I contend, is the implicit thinking that rightly makes us expect that the next humebird will be blue.

Not Habit-Forming

Let me give what I think is a clear demonstration that Hume’s ‘habit’ is not what is responsible for our forming inductive beliefs. Imagine two urns are presented to us. We are informed that one urn contains a million blue beads, while the other contains only one blue bead among a million beads; but we so far have no way of knowing which description applies to which urn. We are then allowed to draw just one bead from one of the urns, without being able to look into either urn; and we find that the one bead we have drawn is blue. Surely we would thus have gained the same sort of confidence that we had about the birds – that the next bead drawn from that particular urn would also be blue. For we would think it extremely probable that the urn from which we randomly drew this one blue bead was not the one with only one blue bead in a million in it, but rather the urn in which all beads were blue. And, contrary to Hume’s account of such beliefs, there would have been no chance here for any habitual expectation to form. Rather, again, we must be thinking that the probable population of beads in that urn from which we selected a bead is the population that would have made most probable that single observation.

A normal person’s method of induction

If instead we were asked to keep selecting beads from an urn about which we had been told nothing, and, if, after having reached in and stirred them up to make sure our sampling was random, we found that we were drawing out one blue bead after another, with each additional observation we would be acquiring the same sort of gradually strengthening conviction that we acquired with our observations of humebirds – that the next one observed would also be blue. For we would know for certain that it was probable that the population of beads in that urn was such as to make probable what we were observing. With each additional bead it would become less probable that the result of ‘pure blue’ would have occurred if the randomly sampled population were not generally blue. Our confidence would be rightly based fully on our implicit inference to the probable general character of the population. No habit-forming need enter into this process.

What helps further to see the non-involvement of habit is the fact that supposing the same number of beads had been gathered from that urn during one dip of a hand (with the hand reaching round randomly to various locations in the urn and accumulating beads from each location), then if, when the withdrawn fist was opened it was seen at once that all of the beads in it were blue, the belief that it was probable that the beads in the urn were generally blue (and that the next bead taken from the urn would therefore also be blue) would be exactly as strong as at the end of the series of one-by-one observations we’ve considered. But in this case, of course, there has clearly been no repetition of any sort that might be thought to have formed a habit.

By similar reasoning, if a coin has landed nothing but heads up in many consecutive tosses, we are rationally required to think that the most probable hypothesis is not that the coin was fair, but that it was loaded, double-headed, or otherwise fixed to land that way. The fair coin hypothesis could be true with that evidence only if something inherently improbable (given that hypothesis) had occurred; and the occurrence of something improbable is necessarily improbable, and therefore not a justifiable thing to believe. We can also apply this thinking to Hume’s famous example of whether we are justified in believing that the sun will rise tomorrow. If the sun has repeatedly risen in the morning, we are increasingly required to think that it is highly probable that it did so because somehow, like a coin repeatedly landing heads, it was fixed to do so; and therefore we are also required to expect that the sun will keep rising in the morning for some time to come.

Based on the conceptual distinctness from each other of successive observations, and of contingently cohering properties like that of blueness and the other humebird characteristics, Hume argued correctly that it would be impossible to demonstrate an a priori necessity for such combinations – through mere examination of the concepts involved in the formulation of the thought – and therefore impossible to justify our inductive expectations in that way. But I have argued that Hume overlooked a proper a priori justification of induction, the one on which our expectations actually do depend, which is the rationally required assignment of probability to the occurrence of competing hypotheses based on whether they make the occurrence of the evidence more or less probable.

Probable Worlds

Let me now return to our earlier question: How can you know that your present experience isn’t due to an artificial stimulation of your brain disembodied in a vat, or to a merely chance and causeless occurrence of its pattern in the absence of any world, even any time, outside of it?

This classic philosophical skepticism regarding the possibility of intellectual justification for judgments about the character of the world beyond its present appearances to your mind – including the rest of time outside this moment’s impressions of memory and anticipations – shows the same inspiration as Hume’s skepticism about induction. Based on the conceptual distinction of any current impression (experience) of the world from the world itself and from times external to that impression (including possible causes of the impression), the skeptic argues correctly for the impossibility of discovering any a priori necessity for any combination of the impression with any particular character of that external world, or even with that world’s existence. However, I maintain that the skeptic, in Humean fashion, is overlooking the a priori justification of empirical inference on which our judgments about the world actually do depend, which is the rational requirement of an assignment of probability to the occurrence of competing hypotheses based on whether the hypotheses make the occurrence of the evidence (including apparent memories and apparently previously formed beliefs and anticipations) more or less probable.

Consider for example the skeptical hypothesis that there simply is no external world. This would make it terrifically improbable that my therefore uncontrolled experience, merely by chance (as it would now have to be) has taken on the disciplined patterns I find it has. Combined with the evidence – my experience – the skeptical hypothesis makes up an inherently improbable package, just like the combination of the hypothesis that a coin was fair with the evidence of its consistently landing heads. And that which is improbable to have occurred is, indeed, improbable to have occured.

We might call the single a priori principle that thus governs one’s overall empirical thinking the highest probability principle. It requires us always to favour in our beliefs, as most probable, that overall context of our current experience that gives the highest probability of having produced the pattern of our current experience. We must do this because it is a necessary truth that the pattern’s being produced in the most probable way is in itself more probable than the pattern’s being produced in any less probable way. Let me just add that sometimes, of course, we must believe that an event which was locally improbable is the most probable to have occurred – but we can only properly believe this when this local improbability is needed in the most probable overall hypothesis

Ad hoc skeptical hypotheses, such as Descartes’ idea of a tricky powerful demon as the sole source of all my experience, must be rejected as extremely improbable, because they contain causes that in their general character would make the evidence improbable. They can only seem to make the evidence probable because of arbitrary and therefore inherently improbable specification of details in the hypothesis, including the idea of a powerful spirit’s specific interest in producing in me an impression of a world that would far more naturally have flowed from the sorts of varied causes that I rightly think to be vastly more probable as sources of my impressions. Any ad hocelaboration in the demon hypothesis would no more increase its likelihood than would an equally ad hoc specification regarding a fair coin – that it just happens to be a coin that lands all heads many times – at increasing the likelihood of the hypothesis of its fairness. In both cases, although the specification may be guaranteed conceptually to get us the evidence, the specification can be conceptually discovered to be utterly arbitrary, and therefore extremely improbable given the general character of the evidence.

© Arnold Zuboff 2014

Arnold Zuboff is a retired lecturer in Philosophy at University College London.