Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Revolver

Dharmender Dhillon views this Guy Ritchie film through Buddhist and Nietzschean lenses.

This is the first (and probably last!) time that a film from Jason Statham’s oeuvre has been put under the microscope in Philosophy Now. Statham is best known for action movies reminiscent of those that went straight to VHS in the 1980s. That notwithstanding, under the direction of Guy Ritchie, 2005’s Revolver provides a hearty chunk to philosophically digest. Panned by critics and audiences alike upon cinematic release, it has become something of a cult classic amongst the DVD crowd, and there have been internet forums aplenty discussing it, mainly from psychological and/or Buddhist perspectives. However, following on from my review of Black Swan in Issue 86, and still afflicted by Friedrich Nietzsche’s overbearing intellectual shadow, I have not been able to shake the need to examine Revolver through the powerful lenses of the Nietzschescope.

The games people play when the chips are down

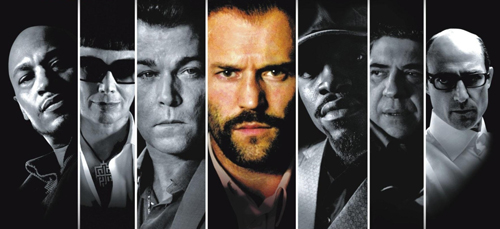

Revolver film images © Samuel Goldwyn Films 2005

Synopsis

Revolver centres on Jake Green (Statham). Released after seven years in solitary incarceration, he gambles his way to a small fortune. He thence seeks to exact revenge on Macha (played by a delightfully overstated Ray Liotta) – a power-hungry casino owner who was the cause of Green’s unjust imprisonment. Green duly humiliates Macha, only to subsequently fall foul of a mysterious disease that leaves him with only three days to live. Meanwhile, Macha orders a hit on Green and executes his entourage. This forces Green to enlist the services of two mysterious loan sharks, Avi and Zack, who promise him safety in exchange for all his money, along with his unquestioning compliance with their demands. We watch Green’s turmoil through the supposed last few days of his life as he loses all control. As director Ritchie remarked in an interview, “there’s nothing quite like death looming on the horizon to precipitate events.”

Key Themes

Four key quotations appear during the opening credits of the film, and appear as themes throughout the film, through the explicit presentation of the quote, the paraphrasing of the quote by a character, and the repetition of it both explicitly and implicitly. They are: “The only way to get smarter is by playing a smarter opponent” (The Fundamentals of Chess, 1875); “There is no avoiding war, it can only be postponed to the advantage of your enemy” (Niccolò Machiavelli, 1502); “The greatest enemy will hide in the last place you would ever look” (Julius Caesar, 75 BCE); and “The first rule of business, protect your investment” (Etiquette of the Banker, 1775).

These quotes can be grouped under two sub-headings: The Ego and Self-War. First I will focus upon the ego.

The Ego

Green’s desire to exact revenge upon Macha is a result of his ego and intertwined notions of self-worth and intelligence. As ‘merchants’ with regard to our own lives, we fight tooth and nail to ‘protect our investment’, meaning our notions of our self-importance and what we deserve. Indeed, Green remarks en route to exacting his revenge that Macha “must pay: it’s cause and effect.” Yet upon exacting his revenge, his subsequent woes lead him to realize that it’s not the conquest of external enemies, real or imagined, that leads to self-mastery, but understanding that one is playing a game with oneself, and that this is the product of one’s ego. External, transient and contingent victories and defeats are fleeting distractions. Once this is fully grasped, one can choose to work towards the possibility of self-mastery, or what in Buddhist thought is known as liberation (moksha) from the wheel of suffering (samsara). Thus the only battle truly worth engaging in is with the smartest opponent one can fathom: oneself.

Later, having been stripped of his material wealth and his control over his own physical and emotional health, Green reaches a breaking point and enters into a heated exchange with his egotistical self. This is represented in the film’s most striking scene. Green is trapped in an elevator stuck on the thirteenth floor of Macha’s headquarters. Instead of acting upon his egotistical desire to kill Macha, he has apologized to his nemesis and asked for his forgiveness. In the elevator Green observes his own ego retaliate against its lack of influence over his actions. Realizing that conquering his external enemies and accumulating material wealth will not bring him peace, he turns upon himself in an act of desperation, and finds the enemy he had hitherto been avoiding.

After this internal battle in the elevator, Green is depicted as having achieved a measure of inner harmony. This is juxtaposed with Macha’s attitude. He’s rattled by his enemy’s new-found serenity, and is depicted as an emotional wreck whose ego needs the fear of others to feel satisfied in its own being.

Statham as Green

Self War

Ritchie has remarked that he did not consider the movie to have any overt message other than “there’s no such thing as an external enemy.” He further mused that “this is not a story about morals … this is simply a story about the game, and there is no right or wrong … We’re all players within our own little games.” This echoes Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), and leads us nicely onto a discussion of the Nietzschean themes prevalent in the film.

As an ethical thinker concerned with what an individual steeped within what he deemed to be a ‘decadent’ contemporary European culture ought to do, Nietzsche advocated self-war for the possibility of self-mastery at the possible expense of any given social or cultural morality. As Nietzsche argued in one of his mature works, the aptly-titled Beyond Good and Evil (1886): “One must subject oneself to one’s own tests … although they constitute perhaps the most dangerous game one can play, and are in the end tests made only before ourselves and before no other judge” (Section 41).

Green is depicted as having spent his time in solitary learning how to become the consummate con-artist, and his skills serve him well in the accumulation of his fortune and in his ability to humiliate Macha. But in spite of demonstrating a mastery of the ‘rules of society’ – of how to get rich and exact revenge – he still suffers immeasurably when he has to forfeit his wealth, which he knows is transient and contingent, and when facing his fear of losing his life, which also he knows is transient. In this confusion he is shown to embody Nietzsche’s dictum in another of his mature works, On The Genealogy of Morals (1887), that “we are unknown to ourselves, we men of knowledge – and with good reason. We have never sought ourselves – how could it happen that we should ever find ourselves?” (Section 15).

One thing the film does particularly well is to superimpose Green’s descent into inner turmoil upon his realization of the irony that his not-insignificant ability as a confidence trickster has been instrumental in concealing his greatest enemy, namely, his own ego, from himself. Then in the film’s key scene in the elevator, we observe Green working out the adage in Nietzsche’s notebooks (collected under the title The Will to Power) that: “To become master of the chaos one is; to compel one’s chaos to become form: to become logical, simple, unambiguous, mathematics, law – that is the grand ambition here” (Section 842, from an entry dated 1888). And so, following his flight of liberation from his egotistical self, Green is depicted as having entered a state of bliss, beyond the cycle of the joys of victory and the agony of defeat. Indeed, in juxtaposition with his remark that “the harder the defeat, the sweeter the victory” upon having successfully exacted his revenge upon Macha earlier on in the film, in the final acts of the movie, Green is arguably a Nietzschean ‘overman’ at least insofar as he has successfully traversed the prevalent morality of his culture (avarice, revenge), and is thus ‘beyond good and evil’. As Nietzsche argues in the Genealogy: “to be incapable of taking one’s enemies, one’s accidents, even one’s misdeeds seriously for very long – that is the sign of strong, full natures, in whom there is an excess of the power to form, to mould, to recuperate, and to forget” (First Essay, Section 10).

As we watch Green’s liberation unfold, we see a most unHollywood of final acts, insofar as the hero is shown to not be gun-toting and out to exact justice, but rather to be ‘beyond good and evil’ insofar as he can observe his once-nemesis Macha hold a gun to the head of a child – Greene’s niece – with compassion for both, emanating a fearlessness and an understanding that, like Macha, he too was once a mere lapdog of his egotistical self. Having forfeited his wealth and social status, not to mention not knowing how long his health may hold out, Greene has become “more humane” insofar as he can endure injury “without suffering” such that this stoic endurance “becomes the actual measure of his wealth” (On The Genealogy of Morals, Second Essay, Section 10). Green’s ability, or better put, his realisation of his ability to forgive, is emblematic of his victory over his egotistical self and his mastery of the chaos that he is.

© Dharmender S. Dhillon 2017

Dharmender Dhillon is still a doctoral candidate at Cardiff University. He hopes to one day become a recovering Nietzschean.