Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Socrates, Plato and Modern Life

Rediscovering Plato’s Vision

Mark Vernon sees Plato in an old light.

It’s a frustrating time to be a fan of Plato. Public intellectuals routinely misrepresent him, and it’s hard to find courses that can unveil the richness of insight and meaning which the best thinkers of twenty-three centuries, from Plotinus to Iris Murdoch, have discerned in his dialogues.

Take one common misapprehension – that Plato was a body-soul dualist, loathing the body and loving the soul. Yet Plato clearly tells us in The Republic that it’s an error to relate body and soul as if in a hierarchy. Take another: it’s regularly said that Plato is the godfather of secular philosophy because he trusted the powers of human reason. What’s overlooked is that Plato often remarks on the failure of human rationality, arguing that it’s not human minds that are reliably rational, but divine minds. We humans can, on occasion, mirror such true intelligence. We can hope to track its paths; but only as a shadow tracks its body.

My sense is that more is lost in these misreadings than just the brilliance of the philosopher. We live in an age of widespread depression and ecological crisis. Emptiness and ennui are a characteristic of our age on the one hand, and on the other, it seems beyond our collective reach to connect with the natural world in a way that can motivate the actions required for us not to destroy it. Plato might be a doctor for our times, if we get him right again.

His therapy is one of vision. Or rather, of re-envisaging: discovering a renewed felt connection with the material world. Plato can show us how to think of our bodies as the manifest presences of our souls. He can also open our eyes to a way of understanding nature as a living organism, rather than tinkering with it as a biochemical mechanism. Let’s look first at his sense of what it is to be embodied.

Life In A Body

What comes to mind when you hear the phrase, “There’s a body in the library”? I imagine that it will conjure up images of a murder, or perhaps the need for a medic. ‘Body’ is pretty close to ‘corpse’ in modern parlance. If you like, you can blame René Descartes’ division between material stuff and mental stuff.

It’s not a distinction that would have made sense to Plato in the fourth century BCE. I suspect that if Plato had heard the phrase, it would have conjured up the image of a student industriously grappling with cosmic matters, amidst piles of leathery manuscripts. Back then, soma – the Greek for body – meant the visible manifestation of a living soul. It was the empirically evident side of what it is to be human, and only part of the vast estates accessible to the mind. It was the tangible end of a span of being that reached from the physical world to the domain of invisible spirit.

Contrast that with a common falsehood propagated about Plato. It is said that he loathed the body for the drag it imposes on life. When it came to flesh, Plato is said to have been like the flapping bird who grumbled that flying would be so much easier if it weren’t for the syrupy air. Typically, people who interpret him in this way do so by highlighting a single line from his dialogue the Phaedo. “The body is the prison of the soul,” Plato has Socrates say there. These people treat this phrase as a creedal statement of Platonic doctrine.

However, isolating the line in this way is a hopeless reduction that conceals rather than reveals what Plato is driving at. For one thing, it ignores the other occasions on which, through Socrates, Plato discusses the beauty of the body, the health of the body, the light of the body, the care of the body. What’s lost by pulling out the prison line as if it’s a proof quote, is how, in the same dialogue, Socrates tousles Phaedo’s hair, enjoying its bounce and shine; how Socrates had loved to philosophize in locations like the gymnasium, where body, mind and soul exercised together; and how Plato had probably gained his pen name (his real name was Aristocles) as a pun on the Greek for ‘broad shoulders’. It was an apt moniker. History records that Plato trained with the wrestler Ariston of Argon, and was good enough to take part in the Isthmian Games, the warm-up for the Olympics. How ironic that today ‘Mr Physical’ is routinely taken to be only interested in the spiritual!

Life In A Prison

Let’s put the line back in context. The most obvious detail is that Socrates speaks it whilst he himself is in a prison.

Consider the scene. The year is 399 BC. A few weeks before, Socrates had been tried by an Athenian jury, and found guilty. Now, he’s locked in a cell. It’s his final day, as shortly he must drink the hemlock that will kill him. His friends have gathered to give him company and support. Some are tearful; others are losing faith. Remembering all this gives the phrase a specific resonance, inviting contemplation. Plato is taking a Greek pun, ‘soma sema’ – ‘body equals tomb’ – and pressing it. What’s key, Socrates aims to show his friends, is having an appropriate relationship to your body. Put it like this, as Plato does in the Republic: do the boundaries of your body share the boundaries of your spirit? Socrates had long been fascinated with how the body’s beauty relates to the soaring capacities of the mind and soul. To deploy a metaphor Plato uses in the Symposium: how might the body’s glint of bronze awaken you to the gleam of gold of the soul? On the last day of his life, Socrates is encouraging his followers to sense how the transcendence they’ve glimpsed with him in embodied life is but a foretaste of the vision to come. He is forcing them to consider that death might, in a sense, be good: the fulfillment of embodied life, not its end.

The phrase “The body is the prison of the soul” also echoes one of Plato’s best-known allegories, that of the Cave, in which Plato imagines humans as helpless prisoners, chained by the small-mindedness that confines us. But on the last day of his life, Socrates is no helpless prisoner, in spite of how it looked to the Athenians.

As a genius author, Plato was playing with the possible meanings of ‘soma sema’. You could say that the comment about the soul’s embodiment is itself embodied. It’s those commentators who nowadays abstract the phrase and float it around in disembodied space who are the body-deniers. They reveal themselves as the sort of modern philosophers who seek outputs from the human mind treated as a thinking device. It’s philosophy driven by uprooted logic, not felt liveliness: by neat formulas, not suggestive feelings. So if you’ve heard that Plato despised the body, forget it. You’ve been done a disservice. If you’d not heard that before, hold onto your innocence. You’re in a much better place to understand Plato.

In certain respects our times are not unlike Plato’s when it comes to the body. The Athenians loved the body beautiful via the balance and poise of the sculptured athlete. As then, so now, it’s easy to become entranced by lithe bodies and muscular displays, glistening oils and envious glances. But in our lives we don’t just have gyms, but also the promise of genetic engineering and nanotechnology. They’re focused on the body as if to surpass its foibles and flaws. There is an upside, of course: medical interventions. But alongside that we run the tremendous risk of losing sight of what the body is an expression of – that illuminates it and makes life life – namely, what we call the soul, that is, the nature of a person. I think that’s why biomedical advances, whilst astonishing, simultaneously frighten us. There’s a sense of something crucial at stake in their deployment.

Holistic Biology

Plato can help us with that too, through his organicist view of the material world, which we’ll turn to now.

In recent years biology has been moving beyond a biochemically reductive view of life. The days when we could regard ourselves as lumbering robots for our genes, to recall Richard Dawkins’ resonate phrase, are numbered, if not already over. Life for the biologist has become a lot more complex, and arguably, in its intricacy, more beautiful.

I recently attended a conference on what is sometimes called ‘holistic biology’ or the ‘extended evolutionary synthesis’. Although the terms are contested, what the gathering sought to explore is the dynamism in living bodies that is now opening up to scientific investigation, in part because of the enormous computing power that can be brought to bear on life. Samantha Frost talked about epigenetics – the discovery that genes alone don’t shape the body’s responses to the environment, because the expression of genes is modified by the environment. In her book Biocultural Creatures (2016), she describes this as “the body paying attention”: the biochemical agents that effect genes are like ‘notes-to-self to be ready next time’. The body can no longer be regarded as robotic. It is plastic and responsive, she said.

Another speaker was the plant geneticist Ottoline Leyser. She is interested in the multi-layered systems that facilitate the growth and shape of plants; or as she also put it, she is driven by wanting to understand “how plants make decisions.” She argued that asking how plants operate causally has ceased to be a good approach because it’s become clear that biological systems are flooded with continuous feedback, which is very complex to chart. Also, as she pointed out, “plants don’t know that they have parts.”

These developments have led the philosopher Michael Ruse to pose a fundamental question. In biology, there has long been two ways of looking at life: as a mechanism, which can be broken down into parts; and as an organism, which can be explained only by considering the way the whole system works. Organicism is the more ancient approach, while the machine metaphor has come to dominate in modern times. Ruse suggests that perhaps it’s time for organicism to make a comeback.

Its origins reach all the way back to Plato.

Music & Maths

Just as Plato saw the material body as an expression of the immaterial soul, so too he painted a picture of the material cosmos as ensouled. In his dialogue Timaeus, the created universe is marked by its holistic becoming. That is, the universe is more akin to an unfolding process than a whirring clockwork mechanism. This is why Plato introduces the best-known element in that dialogue, the craftsman or demiurge.

However, much as we need to be careful when assuming we know what Plato means by words like ‘body’ and ‘rationality’, so too we must be careful when we read ‘demiurge’. My sense is that people today are inclined to presume it refers to a divine or semi-divine engineer, who tinkers with creation much as a watchmaker tweaks the cogs of a watch. But the Greek, demiourgos, literally means ‘one who works for the people [demos]’. Plato scholar Peter Kalkavage writes, “It is a humble, everyday word and refers to anyone who crafts anything whatsoever.” Rather than translating it as ‘craftsman’, I suggest taking a lead from another set of metaphors in the Timaeus – those of song and music – and, at least here, thinking of the demiurge as a divine musician. You can’t craft music if you only think about it in fragments. A musician crafts separate notes, yes; but in such a way as to create tunes and harmonies. So, too, the demiurge can’t craft the cosmos only by manipulating its parts. Rather, Plato’s cosmic musician strives to make a magnificent idea heard, and judges what is produced by its overall effect and excellence.

The dialogue explores how this supreme artist ponders the project. Timaeus describes how the demiurge may contemplate the beauty the cosmos shows in its harmonies and order, as well as in its serving the good of the people. The demiurge is also a kind of hero, a hero in the ancient world being one who transmits immortal, divine qualities to humankind. Seen in this light, the cosmos becomes a faithful performance of the changeless beauty of the divine, since for all that it is often hard to hear just how the cosmos echoes with godly perfection, it can be trusted to reflect what’s true. (Incidentally, this is a very different vision from the argument made by the advocates of Intelligent Design. For them, the supposed cleverness of cosmic machinery demonstrates that it was made by an engineer God. This is the opposite of organicism. Instead, Plato’s view is that science can offer a sense of the nature of the living cosmos that simultaneously enables us to appreciate its meaning.)

The mathematical sections of the Timeaus need to be understand in this organic, musical way, too. Plato’s understanding of mathematics is also different to our understanding. For example, he had no dedicated words for the features that we spontaneously associate with mathematics, such as ‘quantity’ or ‘analysis’. Instead, he’s interested in the qualities numbers embody. What is it to be one, unity, singular? How does that differ from what’s two, dual, binary? He’s much more drawn to contemplating how numbers participate in these apparently fundamental aspects, or forms, of being. This is why for the ancient Greeks, doing mathematics is caring for the soul. Mathematics is an expression of the cosmic soul, and gaining a feel for ratios and proportions enables us to grasp its dynamics in turn leading to a vision of what’s good, beautiful and true. This was the meaning of the legendary sign that Plato had posted above the entrance to his Academy: ‘Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here’. It wasn’t a ban so much as a statement: anyone ignorant of the harmonies of geometry won’t be able to appreciate the philosophical pursuits of Plato and the Academicians.

What this adds up to is that knowledge, for Plato, is a form of participation in something, not the accumulation of facts. He said that you cannot know about something, you can only know of something because you have become able to share in its being. For instance, only the beautiful soul can know what’s beautiful because the two then chime together. Only the well-ordered psyche can discern the deeper orders of nature, because if the psyche is disordered it will be preoccupied with itself. Only the lover of excellence can glimpse the excellence of changeless Being, because love’s yearning gradually orientates the individual towards it. Coming to know is therefore a moral activity. The cosmos, like the human body, is not merely mechanical in its materiality. We can have a felt participation with it that is indicative of its vitality.

Daemons & Gaia

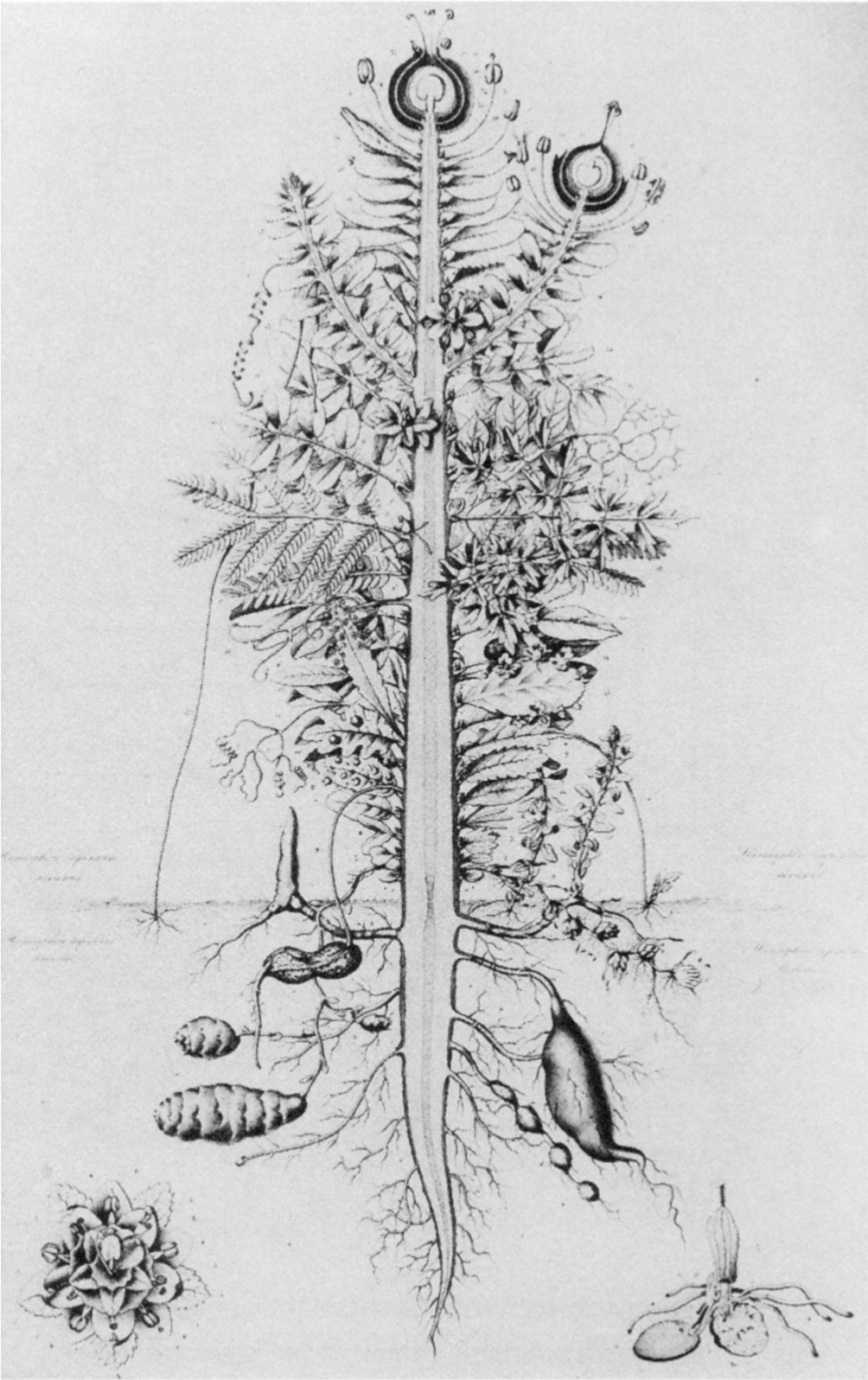

Goethe’s diagram of the original plant

This Platonic organic feeling for nature has, in fact, run quietly alongside the mechanistic approach that otherwise tends to characterize the modern scientific quest. The most obvious manifestation of this is in the frequent references to beauty made by scientists as they describe their research; and also the sense that science reveals nature to be a treasure trove of wonderful things. The night sky and a vivid sunset can be described by the metrics of stellar position or scattered light. But that’s only to appreciate the outer aspects. The inner aspect, which generates the wonder, is more like a buzz than a measurement. You feel it whenever a scientist describes something against the backdrop of a brilliant night sky or dramatic landscape. The backdrop is not incidental: it’s not just the sugar that sweetens the scientific pill. It’s part of resonating with the living cosmos. According to Plato, this is necessary for the more abstract side of science to get off the ground. The intelligence of the mind must learn to participate in nature’s intelligibility, and popular science, perhaps inadvertently, highlights this intimate organic relationship.

There are provable results of Plato’s cosmology, too. Newton, for example, was fascinated by Plato’s ideas about daemons – the spiritual go-betweens that frequent the cosmic soul and convey forces such as love. Current scholarship suggests that this inspired Newton’s conception of ‘action at a distance’, and so, gravity. More recently, Plato lies behind the creation of the Gaia hypothesis which postulates that our entire planet is in some sense a self-regulating organism. James Lovelock, who formulated the hypothesis in the 1970s, was inspired by William Golding. The novelist gave Lovelock the word ‘Gaia’. Golding, in turn, was inspired by the German tradition of organicism that reached back to Goethe; and from Goethe back to Plato. The system scientist Tim Lenton has written about Lovelock’s “keen ability to intuit the behaviour of whole systems, even if he cannot (at least at first) explain how they work in a mechanistic sense.” In other words, Gaia is an example of organicism and mechanism working in harmony.

Plato & The Imagination

The Gaia hypothesis has found favour in the popular imagination. This is not to denigrate it. Quite the opposite, because it is often in the popular imagination (as in popular science) that Plato’s vision of the cosmos, of the ensouled nature of embodied materiality, flourishes.

All of Plato’s dialogues aim at awakening such a felt appreciation of the non-material dimension of life. Plato writes in the so-called Seventh Letter that this is like a lightening flash that opens not the physical eye but the eye of the soul. It’s this perception which Plato asks us to reach towards when we appreciate a beautiful body: what do its contours say about inner beauty, or Beauty itself?

Our times need Plato’s therapy. And although it is a frustrating time to be a fan of Plato, we can reconnect with his genius. When you read him, or read about him, remember to be wary of key words, and of the meanings that get lost. And take your imagination with you. Let it run. In spite of the many misrepresentations and misapprehensions, Plato’s arguments and myths, puzzles and poetry, can still unleash his vision in you.

© Dr Mark Vernon 2017

Mark Vernon is the author of The Idler Guide to Ancient Philosophy (Idler Books, 2015). For more, see www.markvernon.com.