Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Locke’s Question to Berkeley

Alessandro Colarossi imagines a perceptive conversation about reality.

Imagine Locke and Berkeley enjoying a stroll together around Oxford’s Christ Church Meadow, talking philosophy. Biting into an apple from one of the trees, Locke asks, “George, the taste of this apple right now tells me more about myself than about the apple. And isn’t there a lot about the apple that I am simply not getting, and am unable to get, from my tasting it?”

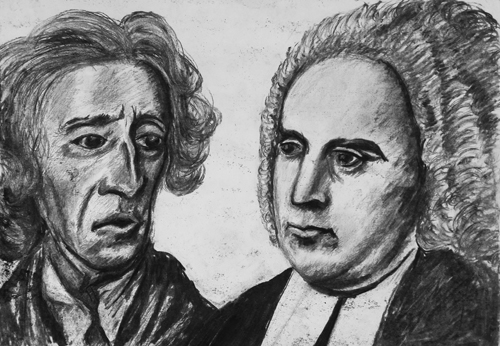

Locke & Berkeley talking

© Athamos Stradis 2019

John Locke (1632-1704) and George Berkeley (1685-1753) never actually met, although both believed that all our knowledge originally comes from our senses. However, they had very different views about the nature of the reality our experiences reveal. According to Berkeley, objects are constituted by ideas and so are perceiver-dependent and do not exist without a mind perceiving them: his motto is ‘to be is to be perceived’. Locke, on the other hand, thinks that the external world exists independent of minds, and that objects in the external world possess so-called ‘primary qualities’. The primary qualities comprise the physical nature of a thing. Our senses interact with these primary qualities to give rise to ‘secondary qualities’ (a.k.a sensations), such as colour, taste, and smell. Considering these two perspectives, I will propose an answer that Berkeley would give to Locke if Locke asked him whether or not there were more to an apple than could be discerned by a person sensing it. Berkeley would argue that there is nothing in the apple over and above the ideas formed of it based on sense experience, since to him the apple consists of nothing other than one’s sensory experience of it (a sensory experience of an object is an ‘idea’ of it in both Berkeley’s and Locke’s terminology). I will then argue that this response would not be plausible for two reasons. First, it fails to recognize the inherent complexity that objects possess. Second, it fails to account for mistakes in perception.

Berkeley’s World

Berkeley would respond to Locke’s question by saying it’s incoherent or falsely founded, because the apple, according to Berkeley, does not have any existence independent of our perception of it. Rather, the existence of the apple consists of a collection of ideas in minds, and therefore the reality of the apple is exhausted by the various perceptions of it.

Berkeley rejects Locke’s notion of material substance. He argues that the words ‘material’ and ‘substance’ cannot refer to the qualities we perceive an object to have independent of minds, such as its “figure, motion and other sensible qualities”, since ‘material’ and ‘substance’ are themselves ideas in the mind (A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, p.29, 1710). Indeed, for Berkeley, to talk about ideas of things not in the mind is a straightforward contradiction.

Berkeley also claims that because our thoughts and ideas of objects are their reality, our perception and thoughts are an accurate representation of the reality of things. In saying this, Berkeley is saying that his principles are opposed to skepticism. If he is aware of perceiving something, this awareness alone is enough evidence to not doubt reality. Specifically, he states that there is no need to question the relation between an idea and the existence of the thing, because, as he says, “that what I see, hear and feel does exist, that is to say, is perceived by me, I no more doubt than I do of my own being” (p.38).

Berkeley’s idealism prompts us to question what populates our minds with the various thoughts and ideas. He states that upon opening his eyes, it is not in his power to be able to choose what his senses will perceive (p.34). This leads him to believe that the vast array of ideas in his mind cannot be created by his own will. They must be imprinted on his mind by “some other will or spirit that produces them.” Specifically, our ideas are imprinted on us by the will of a spirit more powerful and capable than ourselves – namely, God. He also states that the overall “steadiness, order and coherence” shows that God does not give us our ideas without reason. According to (Bishop) Berkeley, this shows that God is a wise and benevolent designer of our ideas. This in turn allows Berkeley to conclude that his ideas and experiences are part of the natural order of things governed by God. Therefore we can be sure that the experiences and sensations that we have when biting into an apple are fully proportionate to the apple itself, because a wise and benevolent God who governs the laws of nature and our ideas would not deceive us.

Not Ideal

The first difficulty that arises for Berkeley from Locke’s question relates to the notion that objects consist of nothing other than our ideas (or sensations) of them. Investigation into the structure of objects demonstrates that our senses do not tell us everything there is to know about them, but rather that there is always more to discover. When we scientifically examine objects we notice that they contain a great deal more complexity than is apparent to our senses, and this complexity pre-exists our knowledge and perception of it. For instance, any physical object has an atomic structure that is not perceivable without specialist scientific instruments. This alone indicates that there must be more to an apple than the simple ideas we form of it through our senses. Therefore Berkeley’s metaphysics is insufficient for explaining the nature of objects.

Locke would agree with this objection, arguing that our ideas of objects are based on their secondary qualities, which are dependent on an object’s primary qualities, which exist independent of our perception of the objects. This illustrates that we cannot even infer all the secondary (sensory) qualities an object could provide if we only have a normal human sense of its qualities.

This objection allows us to question Berkeley’s theory further. Why would a wise and benevolent God give our mind the idea of an apple and not allow us to fully experience the possible range of its sensations?

A second problem for Berkeley’s theory is that it is unable to account for errors in perception. Berkeley’s idealism denounces all skepticism: we must trust the input of our senses. Furthermore, Berkeley presumes that there are no mind-independent objects for us to compare and measure the validity of our ideas against. We must just accept that all of our ideas constitute the various attributes of an object. How then can we account for the possibility of error? For example, if we have an idea of a stick in water that appears to be bent we must accept it as true because not only has a wise and benevolent God given us this idea but there is no external reality to which our idea can be compared to see if it is correct or incorrect. In response Berkeley would perhaps say that objects are exactly as they appear to us in our minds. But Berkeley’s idealism here ignores common sense.

Ultimately, Berkeley’s response to Locke is that when biting into an apple there is nothing other than the idea of the apple in our mind. In other words, there are no qualities in the apple over and above those available to human sense and cognition. However, this answer led to two fundamental problems. The first was its inability to account for the fact that we don’t experience all the qualities of an object. Specifically, there is an abundance of initially-unobserved complexity found in objects that we uncover as we investigate the objects further. This indicates that our senses do not exhaust an object, and so strongly suggests that some (primary) qualities in objects pre-exist our sensory acquaintance with them. The second problem with Berkeley’s response is that it is unable to account for error. The fact that we can be mistaken about what it is we see indicates that there is the possibility of a ‘mismatch’ between perception and reality. This mismatch could only occur if there was an external, mind-independent reality in which objects existed. These problems indicate that Berkeley’s idealism is implausible.

© Alessandro Colarossi 2019

Alessandro Colarossi is a Technical Consultant from Toronto. He has a BA in Philosophy from York University, and an Advanced Diploma in Systems Analysis from Sheridan College, Toronto.