Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Philosophical Haiku

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900)

by Terence Green

God dies, void beckons

Moral slaves to human fears:

Beyond, salvation.

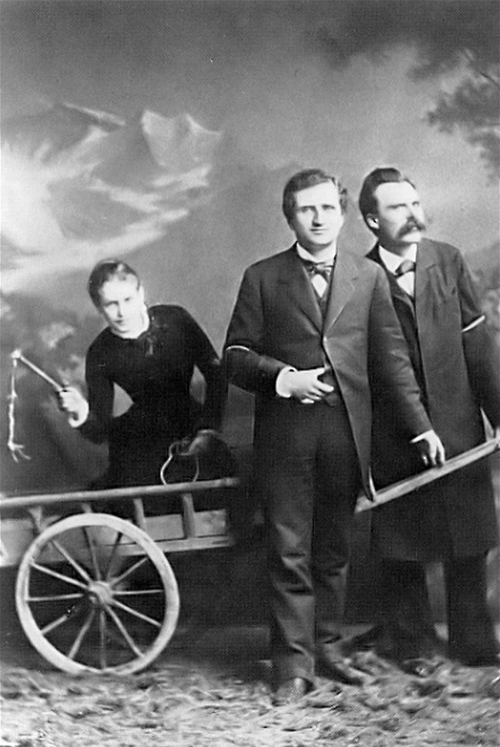

Friedrich Nietzsche with his friends Lou Salome and Paul Ree

Beloved especially by young men who believe that he’s speaking directly to their alienated souls, there is considerably more to Friedrich Nietzsche than existential angst. His reputation also suffered at the hands of his horrid sister, who allowed his appropriation by the Nazis – made possible by her editing and massive distortion of his unpublished writings. As a philosopher, poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer, Nietzsche wrote a swathe of brilliant works touching on religion, philosophy, morality, and language, written with an aphoristic, ironic and metaphorical lyricism.

The end of the nineteenth century in Europe, Nietzsche observed, was an era verging on moral nihilism. A critical culture had destroyed people’s faith in God (“God is dead, and we have killed him!” Nietzsche’s prophet Zarathustra proclaimed), but it could offer nothing useful in His stead. The death of God had cast people adrift in the icy dark of the cosmos. Along with heaven and political progress, science’s promise of ultimate knowledge would soon be thrown on the pile of unachievable utopias. What Nietzsche termed ‘slave morality’ dominated society. People were held back by their petty needs and weaknesses, and deceived into upholding moral values that encouraged passivity. Nietzsche despised the prejudices and fears of the mediocre masses, and took it upon himself to discover a way of living that was life-enhancing in the face of the looming nihilism. We can rescue ourselves, he taught, by going beyond the traditional moral systems – marked by the ideas of good and evil – to attain a state in which we choose for ourselves how to live – a way that is ‘faithful to the earth’. For Nietzsche, the creative artist, whose unbowed will is expressed through the act of creation, is the embodiment of the new man, the Übermensch. His attitude to women was, shall we say, ambivalent – he once observed that when visiting a woman, one must remember to take a whip! (I suppose it makes a change from chocolate or flowers.) Yet he himself had weaknesses that were ultimately anything but life-enhancing for him. In early 1889 he collapsed and slipped beyond good and evil, into madness. This did not make him stronger. He died eleven years later.

© Terence Green 2019

Terence is a writer, historian, and lecturer, and lives with his wife and their dog in Paekakariki, NZ.