Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Letters

Letters

Philosophy Fought the Law • Remembering a Great Philosopher • Failure to Relate • Logic & Logos • I-DNA? I Do Not Agree • Rossen’s Universal Knowbots • Thinking About Thinking About Thinking

Philosophy Fought the Law

Dear Editor: If caught by the police, Luke Tarassenko (short story in Issue 134) couldn’t claim he had done no wrong by knocking the escapologist out with a heavy weight, to carry out his instruction to make it ‘as hard as possible’ to escape from the water tank. Hitting him over the head is not a reasonable compliance with his wishes; and the law requires that actions should be ‘reasonable’. Clearly what Tarassenko did was not reasonable (and the court is the judge of what is reasonable). Neither could he claim he couldn’t help himself, that he was a slave of determinism. The law assumes free will – that people can do or not do harmful things. If this were otherwise, then nobody would ever be guilty of anything. Tarassenko would probably be charged with grievous bodily harm, and if found guilty, would be imprisoned. Philosophy cannot win against the Law!

Peter Windle, Newcastle upon Tyne

Remembering a Great Philosopher

Dear Editor: Reminders of our mortality come in many forms. The latest for me appears in Issue 134 of Philosophy Now in the ‘News’ section, on Bryan Magee’s death on 26 July this year, aged 89. His belief “in the importance of bringing philosophy to a wider audience” was reflected in his TV shows, including The Great Philosophers, and a book of the same title in 1987. This edited version was achieved with the cooperation of each of his interviewees so that, in Magee’s words, “the book would have a life of its own independent of the television programmes” (p.11). I was part of that wider audience able to benefit from the fifteen dialogues. They were demanding, but engaging and informative, significantly because of Magee’s ability to clarify difficult concepts and arguments. I drew on their substance in my professional work, and in life more generally. Their relevance for me certainly persists and is of ‘imperishable value’, to use the words of John Maier’s obituary in Prospect magazine.

Reviewing my video copy I found the appearances of Isaiah Berlin, Iris Murdoch and Noam Chomsky I half remembered occurred not in The Great Philosophers book or TV series, but in Men of Ideas (1978). Thankfully I found some of these earlier dialogues on the net.

Colin Brookes, Leicestershire

Failure to Relate

Dear Editor: The article by Waqas Ahmed in Issue 134, ‘The Mind of Leonardo da Vinci’, described a ‘systems thinker’ as someone concerned with fluency across disciplines and relationships more than objects – relationships being more important than objects in any context. Yet don’t even the closing five minutes of Gone With The Wind (or the last three years of Brexit) exemplify the highly problematic nature of many relationships?

A fluency in pursuing and knowing multiple perspectives can overcome difficulties, Ahmed implies. Hence, as well as an understanding of the curriculum, a college history tutor also needs a deep grasp of educational psychology (including memory, human individuality, diet and IQ), adolescent and parent relationships, multivariate analysis, ever-changing findings on social class, and, on behalf of one hundred grateful students, some way to pull the many strands of these concepts into a day’s lesson plan!

Backgrounds in maths, biology, and cybernetics certainly helped Fritjof Capra and Ludwig von Bertlanaffy assemble the framework called ‘Systems Thinking’ – a discipline now ‘recognised in many fields’. However, no examples are given of modern systems research. Instead, the article presents opaque phrases likely to bemuse curious readers: for instance: ‘everything is inextricably connected’; or that ‘epistemological unity allows one to be elevated to a higher perspective’.

Although the rip-roaring success of the ‘hard’ science conducted by Newton, Galileo, and Boyle cannot be repeated in more complex social settings, systems thinking needs to be a practical approach expressed in clear terms, not make incredible demands on practitioners. Leonardo da Vinci was apparently some kind of pathological lateral thinker; if the systems discipline is to be shared by lay people, guidelines for its application must not require them to possess extreme mindsets.

Neil Richardson, Kirkheaton

Logic & Logos

Dear Editor: In Issue 134 Raymond Tallis quotes the ingenious ‘proof’ of Daniel Kodaj that God does not exist. Kodaj argues from three premises:

1. Belief in God causes evil.

2. If God exists, then God wants us to believe in God.

3. If God exists, then God does not want us to do anything that causes evil.

The third premise is inconsistent with the second one when taken with the first premise. All three premises cannot be true. But certainly the first premise is only a partial truth. Religious belief also makes us do good – just as secular ideologies also make us do evil, as Tallis allows. Valid conclusions cannot be drawn from faulty, inconsistent premises.

The problem of evil is the main argument for atheism: if God is benign, omnipotent and all-knowing, how could he allow both human immorality and natural disasters, which cause his creatures so much misery? But God can’t do what’s logically impossible: he can’t take simultaneous contradictory actions, or make circles with corners. He couldn’t let us choose freely between good and evil without allowing us to choose evil. So perhaps in a world in which beings with a moral sense could evolve, natural disasters are inevitable. Or perhaps an evil god is in perpetual conflict with a good god, as Zoroastrians believe.

There is no way of proving or disproving the existence of God, so agnosticism is the only rational attitude. But beneficial beliefs are not necessarily based on evidence and reason; they can arise from culture and emotion.

Allen Shaw, Leeds

I-DNA? I Do Not Agree

Dear Editor: Personal identity is an intractable problem for philosophers, maybe impossible. Theories of psychology, body, and brain – or some composite of them – all have their pitfalls. Still, it does not follow that there is no such thing as identity, nor that we have nothing to work with.

Raymond Keogh’s article ‘DNA and the Identity Crisis’ in Issue 133 attempts to ground the conversation about identity in science. Fair enough. But his veneration of DNA in producing what we call the person surely represents scientism of the worst kind. A better starting place for thinking of personal identity lies in perspective. Importantly, perspectives themselves have no place in the material realm, since nothing in matter confers an appearance on itself. Thus, it is only by virtue of our self-consciousness that DNA can even enter the conversation about what we are.

Individuals confront their existence and identity as a problem to be solved. Yes, this involves studying our bodies, the things that anchor us in the world, but that’s only part of the story. The self is a perspective on, not a perspective in, the world. With a scientistic outlook, we stand to lose the things that make us human. Notions of freedom, accountability, intention, tensed time, colour, harmony, and quality, are dismissed as by-products of reproductive drives, or as mirages: the subject reduced to an object, perspectives effaced, and replaced with nothing.

True, the wealth of data provided by disciplines such as epigenetics cannot be ignored. Proclivities and traits are correlated with both our individual and our generic genetic make-up. However, the scientific approach to questions of identity and personhood should be tempered by the limitations of the premises that underpin them. The humanities are already being encroached upon by the sciences, and we should protect them – lest we lovers of Philosophy Now face the prospect of DNA Now in the not so distant future.

Thomas Arthurson, Geelong, Australia

Dear Editor: In his enjoyable article in Issue 133, Raymond Keogh holds that the unchanging consistency of our DNA meets the criteria of personal identity, so that we are now free to transfer our ideas of identity from ‘subjective notions’, in favor of ‘an objective concept based on science’. Keogh presents a strong case for those that support the ‘sameness of body’ idea of personal identity. But this criterion is only one of several within the debate. Personally, I question his tacit dismissal of John Locke’s idea of identity being continuity of consciousness, which is arguably a much stronger case. Locke tells us that if a little finger is severed, and the consciousness travels along with the severed finger, then the finger is the person. Personal identity is preserved by and through the unity of consciousness within one continued life. Says Locke, “For, it being the same consciousness that makes a man be himself to himself, personal identity depends on that only.”

Apparently Keogh understands body and person as equivalent terms, shown in his example of the Alzheimer’s sufferer who has lost most of her memory. He says that “she has the same genetic base as she had as an infant without self-awareness.” It is a given that her DNA is the same, but how does this bear at all upon the question ‘is she the same person?’, if one holds that ‘person’ is defined by conscious continuity? A person – an autonomous, rational, moral agent – must be more than body alone.

Jeffrey Laird, Kentucky

Dear Editor: Raymond Keogh claims that “Our DNA remains the same from the first instant of an individual’s existence to his or her last breath.” I challenge that. The science of genetics has entered a new age, and we now know that even if the sequence of nucleotides isn’t altered, the data being transmitted has not remained the same, since external factors can play a role in attaching small strings of atoms to our DNA, thus turning on or off traits in ourselves and altering the DNA passed on to our descendants. So Lamarck’s hypothesis has achieved a major comeback and has left Darwin in the shadow of a much more complex and, in my opinion, more believable theory of evolution. I believe this discovery not only upends our theory of life’s progression from a singularity, but also lends credence to otherwise nearly unbelievable theories such as free will. Perhaps the dogmatic Darwinists of determinism have now been given a second chance to discard their fatalistic apathy.

Nate Kain, Tacoma, Washington

Rossen’s Universal Knowbots

Dear Editor: Many thanks for the excellent Issue 133, and especially for the ‘Einstein vs Logical Positivism’ piece by Rossen Vassilev. It helped me pin down my disquiet about logical positivism and its scientistic claims. I do have a small issue with the terminology. Vassilev uses the terms ‘hypothesis’ and ‘theory’ as if they are interchangeable, but they represent quite different states of knowledge. A hypothesis is an idea which works logically within the confines of current knowledge, but which has no experimental or direct physical evidence to support it: it is a proposal for a research programme. A theory, however, is a hypothesis which has been tested experimentally and not been proved wrong. The scientific method is the mechanism(s) by which hypotheses become theories (or remain hypotheses, or degenerate back to ideas). In this model, theories such as Newton’s theory of celestial mechanics can degenerate to mere ideas if evidence builds against them – which is why we now tend to refer instead to Newton’s ‘work on’ celestial mechanics. Lee Smolin, for some reason, talks about theory and ‘true theory’, which is misleading. As Popper pointed out, no theory is ever ‘true’.

Where does all this leave the idea of the multiverse, as examined in the article? There is currently no experimental or direct physical evidence; so it cannot be a theory. It does work logically within the confines of quantum mechanics, so we could accept it as a hypothesis. There are, however, competing ideas explaining the problems the multiverse addresses, so it is a disputed hypothesis. We have a different word for competing, mutually-exclusive hypotheses for which we seem unable to gather any scientific evidence: we call them beliefs – and, as Rossen points out, that puts the multiverse in a very different pocket of cognitive endeavour.

What I’ve said makes no difference to Rossen’s carefully-argued case. But I’ve carried out my duties as a linguist. Or at least, that’s what I believe.

Martin Edwardes, London

Dear Editor: In ‘Einstein vs Logical Positivism’, Issue 133, Rossen Vassilev misrepresents the views of Lee Smolin about cosmological inflation. Vassilev states: “Smolin remarks that, ‘The theory of inflation made predictions that seemed dubious’”. But in The Trouble with Physics Smolin actually says: “The theory of inflation made predictions that seemed dubious, until the evidence began to swing toward them a decade ago. As of this writing, a few puzzles remain, but the bulk of the evidence supports the predictions of inflation.” By failing to finish the quote, Vassilev implies that Smolin is sceptical about the scientific status of inflation theory. Perhaps there is a case for Philosophy Now employing someone to check citations.

Furthermore, I can find no evidence for Vassilev’s claim that the theory of inflation requires eleven dimensions of spacetime. I think he may be confusing it with string theory.

John Wake

Thinking About Thinking About Thinking

Dear Editor: In ‘Science and Phenomenology’, Issue 133, Kalina Moskaluk laments that experience is impossible to explore reliably from a first-person perspective because in the process of observing one’s experience, one alters what is being observed. As she says, “paying close attention to phenomena in our experience makes us experience them in a different way than we would without that attentiveness.” If this were so absolutely, one wonders how phenomenologists could gather any information about prereflective experience. But it ain’t necessarily so.

It is quite true that some experiences are not amenable to direct observation. For instance, sometimes I attempt to pay close attention to the act of making a choice. While hiking, say, I stop at a fork in the path and try to watch myself make a decision to go left or right. But while I am watching, no decision takes place. My progress is halted. Only after my attention wanders for a brief instant do I find myself striding along one fork or the other. The act of making a decision seems to be opaque to the reflective gaze.

But there are ways to gather information about prereflective experience. Perhaps the most obvious is to examine those phenomena for which reflection during one’s experience of them makes no difference to the experience. For example, mathematical and logical objects appear to us without perspective. The number three has neither a front nor a back, it does not appear closer or farther away at one time rather than another, and it does not change when one looks at it from a different angle. There is, in fact, no way to view it perspectivally, from left or right or above or below. Whether one is reflecting on one’s perception of such an object during the process of perceiving it or not is irrelevant to this aspect of how it appears.

Another way is through memory. Husserl says that every instance of being conscious of something contains not only an impression of the object’s ‘givenness’ in its current actuality, but a retention of the object as it was perceived a moment ago (as well as a protention of the same object as it is expected to be in the next moment).This retention is overlooked in the ‘natural attitude’ – our mode of being conscious in everyday life. That’s why it’s hard to do phenomenology. But we can notice it if we keep an eye out for it in our experience. One needs to cultivate a certain attitude of watchfulness – a sort of looking out for interesting experiences to catch them when they arise. Such an attitude is more akin to Buddhist mindfulness than to being obsessively self-conscious, and it need not distort our perception. What happens, for instance, when you space out – become distracted, or mentally remote – and forget what you were doing? Obviously, if you were conscious of spacing out, you would not space out. But shortly after you notice you’ve spaced out you can remember what was going on during the ‘space-time’. In that way you can learn something about yourself and your experience of your world that is uniquely available to a first-person perspective.

Moskaluk advises us to “go out and play some phenomenology.” It’s not an impossible task, it just requires practice.

Bill Meacham, USA

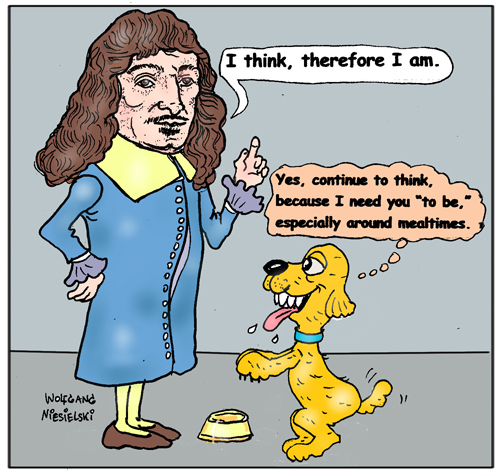

Cartoon © Wolfgang Niesielski 2019

‘I think, therefore I am’ by René Descartes

Once made it to the top of the chart

Among philosophers, because it would link

Our mere existence, to the ability to think

No wonder they put it first on the list

As without thinking they wouldn’t exist.

Wouldn’t be able to make us miserable and glum;

Lucky for them they’ve got Cogito ergo sum!

Wolfgang Niesielski, USA