Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Zombies

Chris Ferbrache wonders why zombie movies have remained so popular for almost a century.

These days you can hardly turn on the television or watch a movie without seeing slack-jawed zombies stumbling or dragging their limbs after a horrified person. For those who are short on reading material, the New York Times bestseller, The Zombie Survival Guide: Complete Protection from the Living Dead by Max Brooks (2003) holds critical information on how to survive the zombie apocalypse. Zombie fever doesn’t stop there. Gun enthusiasts may shoot bleeding zombie targets at their local shooting range. In Canada, you can even learn CPR with the help of zombies from the Heart and Stroke Foundation. And when you are done, you can watch the all-time most popular television series, AMC’s The Walking Dead, which had almost twenty million viewers a week.

If you’re unsure why zombies are so popular, you’re not alone. To wrap our heads round the current zombie invasion, we must start at the beginning.

The Haitian Zonbi

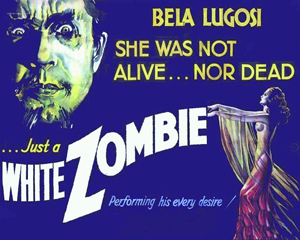

White Zombie poster © United Artists 1932

In the eighteenth century, African slaves were brought to the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti. Forced to convert to Christianity, the slaves developed a way of preserving elements of their indigenous faith while living under religious suppression, by merging African religious traditions with Christianity to form what became known as Voodoo. More than a mere set of rituals, Voodoo rehearsed and reinforced the values of the oppressed.

Haitian bokors (Voodoo sorcerers) played a crucial part in keeping the community in check. Among other things, bokors were reported to have practiced anaesthetizing those who broke with the cultural norms of the village or family. Bokors would poison their victims with tetrodotoxin, a potent and often fatal neurotoxin found in the flesh of the pufferfish (Tetraodontidae) which decreases the pulse and respiration to the point of immeasurability – as illustrated in the book, then film, The Serpent & the Rainbow (Wade E. Davis, 1985, Wes Craven 1988). With the recipient of the toxin appearing dead, they were given a funeral, and buried. Later, hidden by night, the bokor would exhume the body with the hope the person would not have succumbed to hypoxia. The ‘rescued’ person would then be given a continual dose of Datura stramonium, a powerful herb that causes delirium – in addition to the real possibility the victim had lasting brain damage from this process of ‘zombification’. The process was known to destroy the individual’s identity, memory, and free will, leaving the person in an automaton state. Once awake, and continually sedated, the zonbi (Haitian spelling) would be forced to work under the watchful eye of the bokor. Thus, the Haitian zonbi served (or serves, if you believe they still exist), as a reminder and motivator against deviation from the essentials of traditional Haitian culture. Yet although the Voodoo traditions continued for generations, the idea of zonbis radically changed as they became the subjects of horror stories and the Hollywood silver screen.

Originally Hollywood obtained firsthand accounts from researchers who had witnessed Voodoo rituals. In the 1930s, the movie White Zombie (1932) was released. This promoted a somewhat accurate portrayal of the zonbi tradition: under the command of a master, devoid of will, and passive, the wife of a Haitian sugar plantation owner becomes a zonbi. However, she was hardly a threat to those who had not been zonbified. Moreover, the zonbis were limited to one village because they had to be provided a sedating drug to remain in the control of the bokor.

While the depiction of the zonbi was suitable for Haiti, a radical new variant was necessary for non-Haitian settings.

The Non-Haitian Zombie

Night of the Living Dead image © Columbia Pictures 1990

The portrayal of the non-Haitian zombie (note the different spelling) which defined its place in horror culture is George Romero’s 1968 cult film, Night of the Living Dead. Here the zombie was not under the control of a malefactor, but came back to life from the dead (hence the film’s title). Moreover, the zombies were not called zombies in the movie, but more appropriately, ghouls. In Arabic folklore, ghouls were creatures who resided near graveyards and ate human flesh. Since the non-Haitian zombies did not require a controller, these new zombies could replicate in an exponential manner, without limit.

As the non-Haitian zombie evolved, zombification took on a post-apocalyptic theme. Zombies were now portrayed as hyperaggressive, and occasionally with the ability to sprint (as in Dawn of The Dead (2004) or the 2013 movie version of World War Z). The adaptive capacities and rapid mobility of the modern non-Haitian zombie contribute to the breakdown of the social infrastructure, typically centering on an untreatable zombie pandemic or other disaster. It is this zombie subtype that is most popular in today’s culture, and so will be discussed for the remainder of this article.

One must not forget that some people like the gore of flesh-eating zombie movies. However, although watching gore may be entertaining (to some), it’s not the primary reason for the zombie’s relevance today. And although it’s well-known that many people like the thrill of being scared without risking their life, this also does not entirely explain people’s infatuation with zombies and their dominance in today’s culture. For part of the answer here, we must turn to the psychologist Carl Jung.

Zombies Chase Down Carl Jung

Bela Lugosi and friend discover they’re in Philosophy Now

White Zombie image © United Artists 1932

Carl Jung (1875-1961), the founder of analytical psychology, thought people subconsciously store primitive ideas, or latent images, in what he called the collective unconscious. These archetypes were configured in and for human minds by evolution so that we react in various ways to various basic related stimuli. Jung believed that as a result, people are instinctively predisposed to react to situations or dangers that may result in harm – for example, spiders, heights, or the dark – so saving them from the traumas their ancestors encountered. Jung thought various fears are programmed or crystallized like ready-made templates in an individual’s subconscious from birth, even though the individual has yet to encounter the experience. For example, Jungians believe that a child is afraid of the dark because its unknown hazards became associated with the death and injury her ancestors encountered. Thus, a child’s instinctual fear of the dark is a useful protective mechanism even if the risks do not currently exist. According to Jung, these atavistic fears remain deep in the subconscious, becoming manifest in one’s dreams. Perhaps this theory of Jung’s suggests a possible connection between our instinctual fears and the question of why zombies have a noteworthy presence in our culture.

Unknown to Jung at the time of forming his theory, the fear of being chased is one of the most frequent nightmares. So the idea is that zombies trigger fear in us by allowing us to experience our instinctual fear of being chased, but without the potential consequences of being caught. This close link with one of our most common fears is why zombies are so popular amongst movie monsters. The connection between the collective subconscious and nightmares of being chased might also explain why other monsters are significantly less popular. For instance, the werewolf is elusive, and not typically known for its extended chase. Its superior speed means that this beast presents itself in your immediate vicinity after only a short chase. Vampires, as commonly depicted, appear in a manner that leaves the victim with no escape, such as one unveiling itself when the victim is within arm’s reach. Lastly, ghosts are characteristically thought of as being able to appear anywhere, yet typically confined to a specific location. So other popular fictional monsters have little affinity with an extended chase, whereas zombies excel at it. It is also rare for other types of fictional monsters to appear in the overwhelming numbers that zombies do as they maraud across our screens in their grotesque armies.

Zombies embody apocalyptical fears

World War Z image © Paramount Pictures 2013

Zombies Catalyse Social Change

We have seen how zombies might unlock instinctual fears. But there’s another reason zombies remain a part of our culture. Zombies are so malleable that they can take on society’s current fears and concerns, either by carrying out actions which living members of the community are not allowed to perform, or by showing what may happen if society continues its current activities (this idea is gleaned from ‘The Social Significance of Zombies’, in Newsweek for October 27th 2010). For example, in Night of the Living Dead, corpses became reanimated as a result of cosmic radiation. Although this premise may seem far-fetched, the film was made during the Cold War when people were afraid of the effects of radiation from atom bombs and nuclear tests. Shelters were built across the United States and around the world, designed to shield the occupants from nuclear fallout and destruction. So Night of the Living Dead appears to have had an anti-nuclear message too: beware the unknown dangers of working with nuclear energy.

In the movie Sugar Hill (1974), a zonbi-zombie hybrid set in America, African zombies carry out the wishes of their controller, and take on white characters portrayed as bigoted racists. Although civil rights legislation was passed ten years before its filming, racial tensions were still high. In this case, zombies are used to enact a form of social revenge not permitted to oppressed African Americans in real life.

In more recent times, the movie adaptation of World War Z opens with TV images of the problems of our day – global warming, famine, a shortage of clean water, war… etc. At the end of the movie, once a vaccine has been created, the message vocalized is, “It’s given us a chance… help each other… be prepared for anything, our war has just begun.” Here, the zombies are showing us our need for social change and collective preparedness to prevent a similar catastrophe.

In the Disney movie Z-O-M-B-I-E-S (2018), set in a modern high school, the zombies take on a role akin to a minority underclass, and help clarify how groups that are different should be treated – as indicated by Meg Donelly as Addison when she says, “I’m fighting against intolerance.” In this scenario, the zombies represent an outcast racial or ethnic group, allowing teenagers to learn about diversity inclusion without becoming distracted by any underlying biases towards real social groups.

Most recently, The Dead Don’t Die (2019), has a zombie apocalypse triggered by ‘polar fracking’, which results in a shift in the Earth’s axis. Here again the zombies are a result of the actions of naïve humans unaware of their impact on the environment. Like World War Z and Night of the Living Dead, it warns of an existential crisis due to forces more frightening and less preventable even than a contagious agent.

Conclusion

Zombie movies feed our desire to stimulate our primitive fears without real danger, but they also serve as a vehicle for addressing social concerns and ills. This nexus of society’s anxieties with the instinctual fears illuminated by Jung appears to explain why zombies have retained a dominant position in popular culture and refused to stay buried in the graveyard of cinematic history.

© Chris Ferbrache 2020

Chris Ferbrache is a Senior Administrative Analyst for Mariposa County, CA and instructs statistics for the State Center Community College District. Chris holds a BA in Philosophy & Religious Studies and a Master’s in Business Administration from California State University, Fresno.