Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955)

Morgan Sloan studies a Spanish philosopher and public intellectual who wanted to use philosophy to help society.

José Ortega y Gasset is considered to be Spain’s most relevant twentieth century philosopher, possibly even the most relevant of all time. Far from fitting the stereotypical image of a philosopher, sat in an ivory tower, Ortega y Gasset was engaged with his society and its troubles. In his greatest works, including Meditations on Quixote, Invertebrate Spain, and The Revolt of the Masses, philosophical ideas are applied directly to understanding the issues Spanish and European society faced at the time.

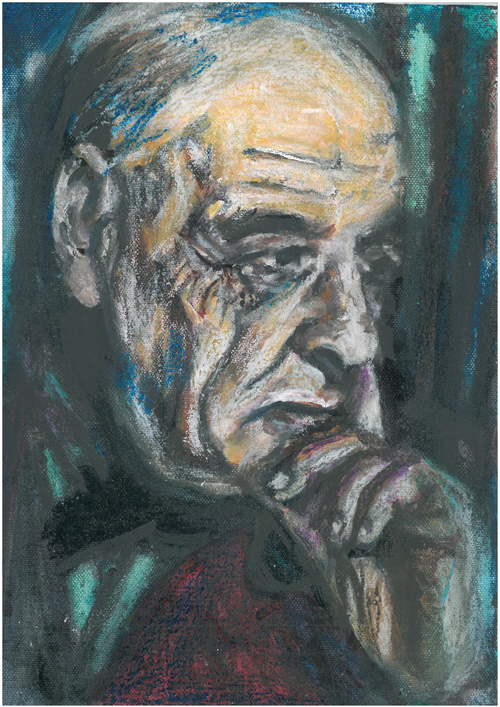

José Ortega y Gasset portrait by Gail Campbell

© Gail Campbell 2020

Born on the 9th May 1883 to a wealthy family in Madrid, Ortega’s parents had many connections in Spanish culture and politics. His father, José Ortega Munilla, was the director of Spain’s prestigious liberal newspaper El Imparcial (founded in 1867 by his maternal grandfather). Thanks to these connections, important Spanish cultural and political icons were regular guests at the family home. José’s parents were more than happy to allow him and his siblings to join in with their discussions, so the young philosopher’s mind was cultivated from an early age.

An early tutor was the first to notice Ortega’s genius, reportedly saying he was his most intelligent pupil and claiming that “sometimes I get the impression that he knows the answer before I’ve stated the question.” Ortega went on to attend a Jesuit school in Malaga, which seems to have had a significant impact on his thought, as the experience highlighted the tight grip held by the Catholic Church over Spanish society. Ortega soon became convinced that the radical conservatism of Spain at the time was holding the country back both socially and culturally. This concern is visible throughout Ortega’s career in his work for a social and cultural reformation.

Perspectivism

After completing his doctorate in Madrid, Ortega left Spain in 1905, on the first of many trips to Germany. He spent the year in Leipzig, where he decidedly committed himself to philosophy, thoroughly investigating the work of Immanuel Kant. In 1907 he visited the country again, this time staying in Marburg. He returned to the same city in 1911 as a Professor of Metaphysics while expecting the first of his four children with Rosa Spottorno, to whom he had been married a year earlier.

His eldest son’s name, Miguel Germán, is an indication of the important influence the country had on Ortega. German science and culture, apparently offering a rational, objective attitude both in the individual and in society, seemed to be just what Spain needed to move forwards. But Ortega also believed that ‘Mediterranean vitality’ was an important quality of the people of Spain which they ought not to lose.

The impact of Germany on Ortega’s thoughts about his own country can be seen in his first major publication, Meditations on Quixote (1914), a book which, far from merely being a commentary on the famous Spanish novel, serves as a summary of Orteguian thought. Influenced by the biologist Jacob Von Uekull’s idea that a living organism must be studied within its environment in order to be understood, Ortega argued that human life must also be understood through its circumstances: “Circumstantial reality makes up the other half of me as a person: I need it to imagine myself and to be my true self,” he wrote. Social status, historical period, nationality, geographic location, and economic situation are all relevant when it comes to understanding how one sees the world and oneself, since they determine our perspective. This idea is summarized in Ortega’s most famous quote: ‘‘I am I and my circumstance, and if I do not save it, I do not save myself.’’ In just the same way that Ortega ventures out into the world down the Guadarrama river near his hometown, or that the Ancient Egyptians would have ventured out down the Nile, we also venture out into the world from our own places of origin. Regardless of how many new ideas you may open yourself to, and no matter how much they change your way of thinking, it will always be you perceiving them; your past experiences, your childhood, your economic and social status, your nationality, your historical period are vital in defining you as a person.

Whilst strolling through the forest near the El Escorial monastery outside of Madrid, where the family frequently took their summer vacations, Ortega recognised that although the idea of a forest implies a large expanse of woodland, it never actually presents itself as such. Instead, we only ever see a tiny portion of a forest whilst walking through it – only a few of the trees and a couple of paths. As we are led down its narrow, shaded pathways, new sections of the forest gradually reveal themselves as we leave the previous ones behind. It’s important to remember, however, that the entire forest never reveals itself to us. In the same way, philosophers, like anyone else searching for any kind of objective truth, must be aware of their circumstances. To generalise, the particular angle from which you see things inevitably affects the way they look, determining your perspective on reality. But although our situation determines our perspective, we can also improve our perspective, by actively seeking to broaden our viewpoints, and making an effort to gain a better understanding, both of our own circumstances and those of others.

What does this mean for us as individuals?

To answer that question it’s helpful to look at Ortega’s famous phrase in full: “I am I and my circumstance, and if I don’t save it, it cannot save me.” So it’s not just a case that we’re determined by our circumstances, we have some duty towards them. Moreover, as living beings, we find ourselves thrown into the world, where we are surrounded by a set of circumstances that we must deal with. Reason is our cognitive response to this reality, our attempt to make sense of the whole forest beyond the small section we directly perceive. Turning the famous conclusion of René Descartes, “I think therefore I am”, on its head, Ortega instead says, “I live therefore I think” (see What is Philosophy?, 1929, English trans. 1963). He means that our reasoning is a result of our life and its circumstances: it is vital. As a result, we must accept that although for us it seems rational to think A is followed by B, people in a different position may just have legitimately reasoned that B is, in fact, followed by A.

Vital reason formed the base of Ortega’s political and philosophical ideas. For instance, Invertebrate Spain, published in 1921, the year of the birth of his daughter Soledad, offered a view of Spain which instead of suppressing or ignoring the regional diversities of Catalonia or the Basque Country described them as ‘organs’ that together formed part of a larger organism.

All of Ortega’s social and political projects tried to make this pluralistic view of a unified Spain a reality. This plural idea of his own country would also later form the base of his understanding of Europe, which he compared to a swarm of many bees taking flight in the same direction.

The Masses

In 1930 King Alfonso XIII abdicated the throne, and Spain’s Second Republic began. Ortega, like many other intellectuals, believed that this was their chance to implement changes the country needed. Having resigned from his post as Professor of Metaphysics at the University of Madrid a few years before, a new political chapter began in the philosopher’s life. In 1931 Ortega founded the Agrupación al Servicio de la República, a group of ‘intellectuals at the service of the republic’. Yet despite his noble intentions, Ortega’s political career was cut short when he resigned from the organization just a year later. Far from making progress, Spanish society was becoming more polarized as tension grew between left and right-wing camps. Strikes, rioting, and public revolts became more frequent – culminating in 1936 with the Spanish Civil War, which ended in 1939 with the establishment of the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

Spanish Civil War: Francoist demonstration in Salamanca, 1937

Not that any of this came as a surprise to Ortega. In his best-known work, The Revolt of the Masses (1930), Ortega develops his idea of the mass man: a person “for whom to live is to be every moment what they already are, without imposing on themselves any effort towards perfection; mere buoys that float on the waves.” Although their natural tendency is to follow those around them, Ortega believed that this person dominated modern society. Control of such people, not just in Spain, but throughout Europe, could have terrible consequences. Their tendency to merely imitate the values, habits, and fashions around them instead of thinking and acting autonomously (or, to use existentialist terminology, authentically) could have severe repercussions.

Whilst this has led to many accusations of elitism, it’s worth noting that the mass person isn’t defined by their class or social status. “All classes have their masses”, Ortega claims. The masses are distinguished from the select minorities by their character. The ‘mediocre’ person, content with blending in with the masses, lacks any desire to better themselves or develop as an individual. Satisfied with doing whatever those around them do, they thereby escape the responsibility of decisions and of considering the moral weight of their actions. By contrast, the ‘select minorities’ strive to improve themselves – to become better people – and never feel a complete sense of accomplishment, no matter how much they do. Both sorts of person, as you will be aware, can be found in all walks of life, with no amount of wealth, titles, or qualifications marking the essential distinction between the two.

With no interest in understanding the world around him, the mass person lacks a sense of perspective. This can be seen, for example, in their relationship with technology. They go about their daily lives thinking of things such as cars, TVs, or smartphones as simple features of the world. The fact that we have been born into a world where we can easily turn on a light, send a text message, or jump into a car and drive anywhere, means that it’s easy to take these things for granted, ignoring the many years of research that went into developing the technology, as well as the struggles of previous generations that led to its foundations. Considering this lack of historic perspective, Ortega suggests that this ‘spoilt child’ is a product of modern society, and he scorns them as a parent might an ungrateful teen. Your circumstances make you who you are, so you ought to get to know them.

Ortega was sure that mass mentality in society caused the rise of the radical political ideologies that led to the fascist regimes spreading across Europe at the time, not forgetting the one that forced him out of his own country. And if mass mentality was something to be worrying about in the 1930s, we should also be worrying about it now. What might Ortega say to us now as we stare at the screens of our smartphones, passively scrolling through news feeds, consuming mass information, and following the latest trends?

The Nation State & the Unification of Europe

After living in France, Argentina, and Portugal, Ortega eventually returned to Spain in 1945, despite the fact that the strict censorship imposed by Franco’s dictatorship made it very difficult for him to continue intellectual activities. Most of his later conferences and lectures took place in other European countries, where his ideas could be expressed more freely. He met the controversial German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) in a conference in Darmstadt in 1951. A conference in Berlin titled ‘Meditations on Europe’ was also noteworthy.

Published posthumously in 1960, Ortega’s resultant book Mediations on Europe discusses the nation-state, its role, and its future. After being forced from his own country by a fascist regime and witnessing two World Wars, it’s hardly surprising that the nation-state was an important topic to Ortega. He believed the issue lay partly in the fact that, whilst the nation-state generates a great deal of fanaticism, we are often incapable of providing an exact definition of one – which however Ortega had already done long ago in The Revolt of the Masses. As he recalls in the conference:

“I will repeat it once again: the reality which we call the State is not the spontaneous coming together of those united by ties of blood. The State begins when groups naturally divided find themselves obliged to live in common. This obligation is not violently forced upon them, but implies an impelling purpose, a common task which is set before the divided groups. Above all, the State is a plan of action and a programme of collaboration. The men are called upon so that together they may do something. The State is neither consanguinity, nor linguistic unity, nor territorial unity, nor proximity of habitation. It is nothing material, inert, fixed, limited. It is pure dynamism – the will to do something in common – and thanks to this the concept of the State is bounded by no physical limits.”

Just like any enterprise, the nation-state has a set of values, insignia through which it is recognized (a flag), and a general set of customs that unite its members, creating cultural coherence amongst them. The nation-state, however, is built upon diversity, and belonging to it does not mean that sub-groups lose their individuality. Be it Catalonia in Spain or Scotland in the UK, belonging to a nation doesn’t remove their spirit as separate entities. And in the same way, all other groups which make up the members of a state do not lose their identity simply by becoming part of the nation: being Spanish doesn’t imply that you are of any particular faith, age, gender, race, and whilst it may be assumed that you speak Spanish, it is not necessarily your mother tongue. Even borders – which might seem like pretty stable definers of a nation – are the present result of centuries of conflict and negotiations. They have constantly changed throughout history, and there’s no reason to think that they won’t do so again in the future. So instead of understanding a nation as something static, bound fast together by metaphysical connections, it should be viewed as a dynamic – something we do instead of something we are. Thanks to historical records, we have a documented account of Rome from its beginning until its fall – its lifespan, you might say. We Europeans have also witnessed the birth of our modern nation-states from the ruins of the Roman Empire, including their growth and incorporation of surrounding communities. But nation-states are also prone to shrink, fall apart, maybe even die. As a work in progress, nations are by no means eternal features that exist naturally on the face of the earth, leaving them open to whatever fate we bestow. As dynamic, ever-changing projects, nations must be open to change and to the incorporation of new groups, whose ideas could contribute to solving their problems and reaching their goals.

Ortega y Gasset in Darmstadt, 1951

For Ortega, a unified Europe would allow this to happen to its nations. The nations of Europe have historically shared experiences and cultural assumptions, as well as common problems and goals. Therefore the collaboration of European nations was essential for their development. But just as the nation-state doesn’t leave the communities that form it stripped of their individuality, Ortega believed there is no reason for a unified Europe to remove the sovereignty or identity of its nations. Comparing Europe to Hellenistic Greece, he suggests that “the Athenian, for example, feels [both] Athenian and Hellenic, like the German feels German and knows himself to be European.” As far as identity is concerned, Ortega had already suggested long before that in Europe “each new uniform principle fertilized diversification.” A unified Europe should not threaten national sovereignty, then; nor, conversely, should national concerns and interests be considered a threat to European unity.

Legacy

Ortega passed away in Madrid in 1955, without seeing the unification of Europe he believed crucial for its future progress. Nor did he see the fall of the Spanish fascist regime that had forced him into exile almost twenty years earlier. And as much as we can speculate whether or not he would have approved of the EU, there’s no question that he foresaw the inevitable need for cooperation amongst European nations to solve common issues – just as they had done many times before throughout history.

Other issues in his work have continued to be relevant since his death, too. As a result of the increasing dependence on mass media and our constant use of social networks as a source of information, the threats posed by mass mentality are more pressing now than ever, not to mention the presence of radicalism in many areas of society.

Although his ideas are dispersed in a seemingly scattered and incoherent manner across the many articles, essays and books he wrote throughout his prolific career, Ortega is very coherent in providing a philosophy that really is vital, going beyond academia and providing an approach to all aspects of our lives, whether that be domestic, social or political, just as the philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome set out to do more than two thousand years ago.

© Morgan Sloan 2020

Morgan Sloan is a graduate of the University of Chester who stumbled upon philosophy whilst roaming the Iberian Peninsula.