Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida by Peter Salmon

Omar Sabbagh on a biography of Jacques Derrida.

Deciding to write a biog raphy of Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), even a predominantly intellectual biography like Peter Salmon’s, must, perhaps, involve a dilemma. As Salmon himself suggests in his Introduction, the temptation to mimic Derrida’s own ‘gnomic, allusive, elusive’ manner of writing can be overwhelming. Yet while saying that Salmon has written a superb intellectual biography that does a terrific job of humanizing a man and thinker often seen or imagined as arcanely inaccessible, we can also mention the more approachable way in which Salmon mirrors for his readers’ benefit some of the gnomic tics of his subject (or is it object?). If there really is, as Derrida says, ‘nothing outside the text’ – meaning that all meaning is text-based, and so susceptible to plural interpretations – then writing a biography in a predominantly plain-spoken manner might seem to be conceptually problematic, no? The book, however, hardly ever fails to intrigue, picking out and deploying moments of Derrida’s life and work, text and context, with a novelistic rhythm.

As the chapters of this book move chronologically through Derrida’s work and life, they make use of epigraphs he employed in his oeuvre, indicating how layered all writing is, including biography. The first quotation comes from Socrates in Plato’s Parmenides (a work obsessed by oneness, coherence and unity), where Socrates says that recursive self-questioning is of the essence of being human, and not the conclusive achievement of insight. The second is from Derrida himself, stating, reluctantly and with a boyish impishness, that he has always loved the beauty of beautiful books. Yet later, Salmon has Derrida saying that the finished form of a material book belies the inconclusive nature and infinite semantic drift of literary meaning, since it seems to falsely indicate some notion of coherence and finishing of meaning. So, in a way, for all the sheer lucidity of Salmon’s book, perhaps he is himself rather impishly doing his own version of a rigorously-sustained philosophical technique, namely, Derrida’s own ‘deconstruction’.

Whether in the writings of Jacques Derrida himself, or in those of his many followers, the idea of there being a centre to meaningful thought, an essential core from which all else is hierarchically derived, is deeply abjured. It would seem that Derrida’s logic is instead ‘oceanic’ – meaning that meaningful truths or insights wend in from many different directions, all given equal status or priority, and no interpretations are primal or more valid than others. In the tidal motions of a sea, how do we prioritise one wave from the next? Simple: we don’t. Thus, one idea denied by the Derrida represented in Salmon’s book, is the idea of any academic’s work being a ‘profession’ separate from the man or woman in all his or her contingent reality. Of course, in a work of intellectual biography, this approach can only commend itself.

In so far as Salmon has written a labour of love, he unites in a kind of haunting spectral mirror himself and his subject, object, because one of the most incisive marks of Derrida’s approach to thinking and writing, language and meaning, is his insistence that philosophizing is, if not autobiographical in a purist sense, deeply, endemically ‘personal’. This can be seen when Salmon is exploring the thoroughly personal motivations of Derrida’s works which, as Salmon details, were nearly always spurred or triggered not by some philosophical agenda but by contingent moments in Derrida’s highly rarefied, intellectual life. It can be seen too in the many ‘historic’ intellectual exchanges Salmon records, such as that between Derrida and John Searle. Derrida attributed some of Searle’s arguments to a psychoanalytical mourning and/or killing of the father – JL Austin in Searle’s particular case!

Salmon’s book does the expected work of an intelligent intellectual biography. His novelistic ability (Salmon is also a novelist) is also a gift for this book, in weaving readable rhythms, shorter paraphrases, and enamoring longueurs between historical, biographical, political, social, ethnic and linguistic contexts, and wonderful glosses of philosophical ideas, which are readable by the average educated man or woman but also never in any sense a dumbing-down. They offer more than enough intellectual context and textual parsing, whether of philosophical history or about Derrida’s more contemporary concerns, ranging from Nietzsche, Freud, and Edmund Husserl, through Heidegger, to Sartre, Lacan and Levinas, Cixous and de Man, among many others.

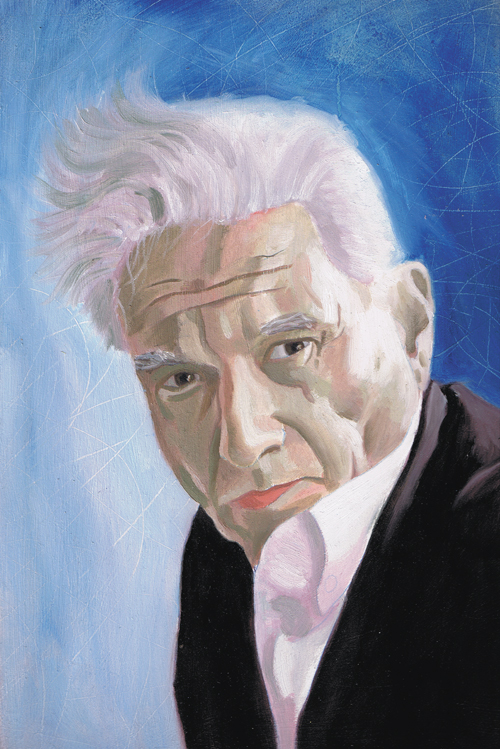

Jacques Derrida by Darren McAndrew

Deconstructing Politics

This is, so far, to speak about Salmon’s biography as it relates to his success as a biographer. However, upon mentioning both Heidegger and de Man, we cannot forget that as well as conflating the (supposed) space between the philosophical and the personal, Derrida saw all his writerly acts as political and politicizing, especially in the second half of his intellectual life, in his choice of subjects upon which to work with his ‘philosophical technique’ of deconstruction.

First is the more philosophical sense of being politicizing and politicised. As Salmon shows, Derrida was engaged in a rigorous critique of Husserl’s search for the origin of meaning or truth. With his famous dictum ‘To the things themselves!’, Husserl had rejected Kant’s split between phenomena and noumena, that is, between appearance and reality. Derrida finds this effort, however colossal, to be confused. Derrida’s central theme and method is to celebrate the paradoxical, contradictory, non-identical, ambi-valent and radically equivocal moments in discourse, ‘philosophical’ (note the scare-quotes) or otherwise. Derrida’s basic argument against Husserl is that even to attempt to originate an ‘origin’ for truth involves communicating it. But as soon as it is expressed (in order, the hope was, to establish the Truth of truth), then because of the way meaningful thought in language can never stop its semantic drift or slippage, in any direction, it instead becomes the origin (as it were) of its non-originariness. That is to say, the origin of truth, when expressed, is not the origin of truth, but only the origin of the expression of ‘truth’! Derrida’s implicit politicization, even at this early stage in his career, leads him to say that when one is searching for some absolute origin, some Form or forms, some essence before existence, or some final, first ‘ground’, one is thereby using metaphysics as ‘violence’. Such purely closed, finished, naming, denotative stances, are never self-justified for Derrida. They always come from some place inside culture and therefore involve or are embedded with political prioritizations, hierarchies, or forms of violence – acts of power and domination. In these terms, Derrida’s deconstruction can be construed as a liberation from violence.

Near the opening of the book, while still in introductory mode and before the chronological progression through the biography, Salmon describes the ‘event’ of Derrida’s entrance onto the world’s intellectual stage with a playfully defiant paper at a conference on structuralism at Johns Hopkins University in 1966. And towards the end of the biography, the controversy at Cambridge in the early 1990s surrounding Derrida being awarded an honorary doctorate is detailed like a counterpoint to this opening ‘event’. His now-infamous lecture on the ‘play’ of the ‘signifier’ at the Johns Hopkins conference is foregrounded by Salmon because it provides the title of his book: Derrida announcing an ‘event’ in the history of the concept of ‘structure’. But the controversy at Cambridge is a nice counterpoint, because it’s after the world-spanning fame set in, and it indicates how controversial Derrida as an intellectual presence was. Many analytical philosophers at Cambridge, having read Derrida or not, slated the honorary award, and argued that he was more of a literary punster than a genuine philosopher.

Salmon discusses a lot of intellectually politicized contexts, biographical or not. The Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser is a persistent presence in the book, accurately portrayed as a rather delicate personality, though a longtime friend of Derrida’s. That said, while such pivotal Althusserian works as Reading Capital and For Marx are duly mentioned with appropriate context, it is made clear how different Althusser’s intellectual instincts were from those of Derrida. As a graduate student Derrida felt he faced a choice between just two available options: the ‘Catholics’ or the ‘Stalinists’. He rejected that dichotomy and this fed into his later attacks on binary oppositions as being philosophically fallacious.

Michel Foucault, of course, is also a repeated presence. As one of Derrida’s doctoral examiners, he wonders whether, given the abstruseness (but brilliance) of Derrida’s work, he should be given an ‘F’ or an ‘A+’. This is the kind of paradox that typified Derrida’s public career. Later, Derrida, calling himself a ‘disciple’, critiques Foucault’s 1961 work Madness and Civilization ; but his criticisms are acknowledged by Foucault and duly applied by the early 1970s, by which time Derrida had already achieved wide fame.

In Salmon’s generally admiring book one exception worthy of note is his willingness to call out Derrida’s slightly mendacious defense of Paul de Man, once scandal broke regarding de Man’s Nazi past. Derrida claimed that de Man had effected a true ‘rupture’ with that soiling past; but Salmon is honest and respectful enough to indicate Derrida’s slight disingenuousness here. But consider this in light of the fact that, further on, at the end of the chapter titled ‘Before the Law’, Derrida in The Politics of Friendship (1994) is seen to be critical of Carl Schmitt’s dichotomy of ‘friend’ and ‘enemy’. Derrida’s deconstruction of this dichotomy is not purely the fruit of his philosophical ‘technique’. The ‘groundless’ experience of friendship for Derrida, its radical ambiguity, is registered, inter alia, by pressing concepts in the very contemporary climate of immigration, borders, and citizenship.

Salmon describes many other political, historical contextualisations, from Derrida’s childhood as a Jewish pied-noir in Algiers – he was originally called ‘Jackie’, after the co-star of Charlie Chaplin’s 1921 movie The Kid – through the upheavals of 1968, to the prodigious outcomes of the feminist movement that Derrida in part influenced. Salmon details not only thinkers and thought, but also factual details – such as the final joining of the female and male wings of the École Normale Superieure in 1985, or the legalization of birth control in France in 1967, or the right for women to work without a husband’s consent, granted in 1965. And we learn that towards the end of his life, Derrida’s use of his ‘philosophical technique’ goes overtly political, in such works as The Politics of Friendship or Spectres of Marx (1993).

Non-Concluding Thoughts

What Salmon has done so successfully and enjoyably here is not only to humanize a greatly influential thinker, relating his gnomic, arcane aura to a man of flesh and blood, but also to show how pivotal thinking can be when it goes radical. The idea that responsible and responsive thought is an investment, not only for politics ‘out there’, or history ‘out there’, but also as a point of intellectual departure, makes this an exciting read.

Deconstruction for Derrida was never the same as destruction. Instead Derrida believed that deconstruction was always already inside any discourse of meaningful language; so his ‘technique’ is not a critique of metaphysics, but a series of playful moves already inside metaphysics, making his interventions a kind of midwifery, disclosing, unveiling, revealing what was always there. And midwifery is not an act of violence, but of deliverance.

Whether viewed as a genius or a charlatan (and Salmon suggests that Derrida himself was never sure he wasn’t a charlatan!), he was most definitely a historically influential and impactful presence. This makes Salmon, in turn, a kind of midwife too. Salmon’s highly personable, but still rigorous, intellectual biography, can for instance speak of Derrida’s Of Grammatology (1967) as ‘gloriously bonkers’ even while giving it due space and weight and elaboration as part of the equivocal nature of a thinker so philosophically enervated by his personal concerns.

A genius, perhaps; but in the light of Salmon’s treatment, nothing like an impostor on the reader’s interest or time.

© Omar Sabbagh 2021

Omar Sabbagh is Associate Professor of English at the School of Arts & Sciences in the American University in Dubai. His latest work is Reading Fiona Sampson: A Study in Contemporary Poetry and Poetics (Anthem Press, 2020). Morning Lit: Portals After Alia is due in 2022.

• An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida, Peter Salmon, Verso Books, 2020, 320 pages, £11.99 hb, ISBN 978-1788732802