Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Philosophical Science

Catherine Malabou & The Continental Philosophy of Brains

Dale DeBakcsy urges rigor in applying science allegorically to philosophical problems.

Continental philosophy has a reputation amongst analytic philosophers as the flighty sibling of Western thought. In the Twentieth Century, whilst the British and Americans slowly and methodically went about the task of Getting Things in Order, the Germans and French had a tendency to leap steps ahead, generating vast new speculative systems with gleeful abandon, grounded in little more than their inexhaustible personal fancy built upon the collective fancy of those who went before. The more Icarian of Continental thinkers have also been reluctant to chain themselves to the sober discoveries of modern science. Whether out of some genuine allegiance to Adorno and Heidegger, or out of fear that, once let in the door, science will take over the whole of philosophy, Continental philosophy has long had an instinctive revulsion against engaging with the leading edge of science research, and above all to the perceived deterministic rigidity of neuroscience.

But philosophers can ignore a field that’s generating substantive answers to millennia-old questions about perception and identity only for so long, and when neuroscientific advances in imaging techniques and molecular scrutiny uncovered new answers to precisely those questions, a few philosophers rose to the challenge. Frenchman Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995) found philosophical significance in the synaptic gap between neurons, while Spaniards Humberto Maturana (b.1928) and Francisco Varela (1946-2001) sought to use discoveries about the role of the environment in gene expression (epigenetics) as a wedge against rigid genetic determinism. But it is with the French philosopher Catherine Malabou (b.1959) that the story of a thorough Continental philosophical engagement with neuroscience well and truly begins. She is at once a great example of what can be accomplished when philosophy and science genuinely engage with each other, and a great cautionary tale of what can happen if philosophy becomes over-eager in its allegorization of scientific source material.

Freud, Derrida & Damasio

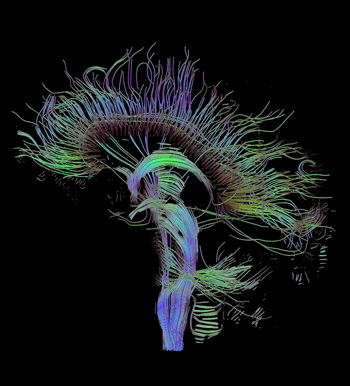

Neural connections in the brain

Neural graphic © Thomas Schultz 2006

Malabou’s starting question on neuroscience is a good one: how do the fundamental assumptions of philosophy and psychoanalysis change once you start admitting the discoveries of neuroscience? For her this question ushers in a centuries-spanning review of European thought, equally redemptive and destructive. Some things clearly have to go. The Freudian assumption that humans are beings of continuity – that everything which has ever happened to us is retained and influences our current personality – cannot long stand in the face of a mound of case histories of people whose personality fundamentally changed after episodes of intense brain trauma. How do you psychoanalytically treat an Alzheimer’s patient? Contrary to Freud’s pre-neuroscientific understanding, personality is neurally based, and any theory which holds beliefs contrary to that assumption, no matter how noble its pedigree, is for the dustbin of history.

At the same time, neuroscience provides many startling instances of support for philosophical theories that seem at first positively allergic to scientific methods. Malabou has deep intellectual ties to the work of the late, great Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), and much of her work can be seen as an attempt to use the insights of neuroscience to lend support to the theories and projects of that Father of Deconstruction. Thus she compares Derrida’s notion of the Otherness of our self-experiencing with neurobiologist Antonio Damasio’s theory that the the biological self has three layers, and finds several intriguing parallels. For Derrida, there is always something elusive about our attempts to experience ourselves, such that whenever we make the attempt to speak with ourselves, or even to let a monologue run in our heads, we are really engaging with nothing but hastily-erected constructs. In Self and Emotional Life (2013), Malabou quotes Derrida’s statement that, “At the very moment when ‘I’ makes its entrance… it signs the possibility or the need for the said ‘I’ (as soon as it touches itself) to address itself, to speak to itself, to treat of itself (in a soliloquy interrupted in advance) as an other” and she argues that this idea is reflected in Damasio’s notion of the multi-layered self. For Damasio, there is a fundamental core to each person, the proto-self, which is engaged in the business of homeostasis – of keeping our bodies alive and in chemical balance – and of which we have no introspective experience whatsoever. It is a complete stranger with which we cannot directly engage, in spite of the fact that it is the foundation upon which the rest of our self is built: what we experience as our self is a series of constructs and networked actions perched atop the proto-self. This series of constructs feeds us a cohesive and streaming imageof the self, but that must of its very nature always be interrogated as an image, that is, a convenient fabrication. To ask to dive deeper than that into the ‘real’ self is as forbidden from a biological perspective as the experiencing of a true ‘I’ is from a Derridean one.

Now we could be uncharitable at this point. The unattainable self of Derrida, and Damasio’s homeostasis-maintaining proto-self, are similar insofar as neither can be consciously interrogated, but they’re different in just about every other way, and equating them is perhaps to take a clearly-stated biological concept and foist a mass of hazily systemic jargon-encrusted guesswork on its back, to the benefit of no one except the odd Derridean seeking validation in a cold and mocking world. But evaluating the attempt in that light is to put continental philosophy and science right back where they started with regard to each other: in complete alienation. Yes, on occasion, what results from the engagement between philosophy and science boils down to a doleful image of hoary philosophers waiting around in the antechamber of science for one of science’s liveried servants to emerge and announce which of Western philosophy’s hunches turned out sort-of right. That’s a sad future for an entire discipline to face; and so it’s understandable that many philosophers, sniffing this future in the wind, have retired to their isolated burrows to write self-referential tracts about Fichte etc until death mercifully takes them. But the relationship between philosophy and science needn’t always work out this way, as Malabou shows when she returns to Damasio’s research in Looking for Spinoza: Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain (2003), this time confirming the notion that emotions order reason. That is to say, emotional responses give meaning to the various choices before us, and thus are the very stuff through which reasoned decisions are made within the whirring chemical abacuses of our brains. Remove that capacity to emotionally weigh decisions, and you remove the very vital force of thinking itself.

Here is a biological discovery with fantastic social consequences: consequences that a philosopher trained in applying ideas to civilization – that is, in ethics – is perfectly suited to investigate. This is not a case of a simple retrospective ‘Turns out you were vaguely right’ slap on the back from science, but of a discovery opening up a new interpretation of the individual’s engagement with society – which can itself become the springboard for a whole new philosophically-brokered approach to public health, social cohesion, and many other ethical issues. Philosophy and science have engaged, and both emerge the better for it.

The Emergent Consciousness of Catherine Malabou portrait by Elizabeth Bevington, 2016

Positive & Negative Charges

Malabou’s works are at their best at moments like these, when she fearlessly tussles with the full implications of modern scientific research and finds ways to relate them to philosophical projects, in order to outline a new and socially-relevant way forward for previously highly abstract strands of thought.

Another such instance comes when she’s relating the impact of stress on the hippocampus – a structure around the center of the brain correlated with the recording of new memories – and the cascading consequences that such stress has for an individual’s ability to relate to others and engage in community activities. This biological realization, fused with Continental philosophical insight on how engagement with Otherness (that is, with other people) is critical for self-definition and growth, leads Malabou to new ideas concerning society’s re-humanizing those who have been pushed to its extremes: for example, to approaches that treat the unemployed with the same level of whole-being concern as is granted those with Alzheimer’s.

However, these moments of positive potential are unfortunately balanced out by many instances where Malabou’s enthusiasm overtakes responsibility, allowing allegory to run away with itself. In such situations the old Continental flightiness grabs the wheel with often embarrassing results.

For instance, in her 2004 book, What Should We Do With Our Brain?, Malabou considers neural plasticity – the ability for often-used neural pathways to strengthen and thereby facilitate learning and even to re-allocate mental function to new areas of the brain to compensate for brain damage. Sadly, she does so in an over-allegorical way. She is dedicated to the idea that this plasticity provides the model for a new political order that emphasizes active resistance to a given regime over merely docile flexible accommodation to it. As she writes, “It must be remarked that plasticity is also the capacity to annihilate the very form it is able to receive or create. We should not forget that plastique… is an explosive substance made of nitroglycerine and nitrocellulose, capable of causing violent explosions. We thus note that plasticity is situated between two extremes: on the one side the sensible image of taking form (sculpture or plastic objects), and on the other side that of the annihilation of all form (explosion). The word plasticity thus unfolds its meaning between sculptural molding and… explosion. From this perspective, to talk about the plasticity of the brain means to see in it not only the creator and receiver of form but also an agency of disobedience to every constituted form, a refusal to submit to a model” (pp.5-6).

Now in Derridean philosophy, an analysis and comparison of words with the same roots and their alternate meanings is seen as a useful device for getting at hidden associations and binarisms in word usage. It can unravel unspoken agendas, and enrich meaning in stunning ways. Here, though, the word chosen, ‘plasticity’, is a rather useful marker for a very specific set of ideas. Does the word ‘plastic’ have other usages? Certainly. Do those meanings then automatically become part of the scientific idea being expressed as ‘neural plasticity’? A very dedicated adherent to the theory of the social construction of science might say “Perhaps”; but the rest of us would have to answer, “Sorry, no: that the word ‘plastic’ is a form of explosive doesn’t mean we get to leapfrog from brain plasticity to explosivity to social revolution, and thereby say, in a weird twist of free-associative transitivity, that neural plasticity implies social revolution.” There are other, similar, cases, too: for instance, stem cells being used as examples of our fundamental and absolute freedom as a species; or a defense of Deleuze’s wobbly poetic treatment of synaptic gaps in the name of creating a freeing defiance from an otherwise decidedly deterministic structure. Certainly Malabou has a point that how we think about our brains has ramifications for how we structure our society, just as our ordering of society informs how we interpret our brains (some of her most engaging analysis comes with her relating a neural networking model of the mind to the decentralized structure of modern capitalism); but you can’t force the brain, through a series of wishful associations, into being something that it isn’t in order to create the world that you would most like to see. Freedom, and rebellion against the corruptions of the extant order, are both lovely notions, but the justification for either of them isn’t going to come from how stem cells can become lung cells, or a fanciful etymology of the word contingently chosen to express the brain’s self-organizational nature.

Malabou’s ideas are not consistently plausible, but that hardly matters. She is attempting to fuse two branches of intellectual endeavor that have been scornful enemies for a century and more; and just making the attempt ought to be enough to earn gratitude to her on both sides of that dizzying divide. But that she has somehow wrought from these first attempts at synthesis a few moments of genuine promise – to ideas not just theoretically interesting, but of immediate import to the improvement of our social lives – that is something remarkable, and for the sake of which her false starts and over-eager linguistic leaps can be enthusiastically forgiven. A way forward has been lit, and there is some sound footing along it; and that is something philosophy has been waiting a long time indeed to hear.

© Dale DeBakcsy 2016

Dale DeBakcsy writes the ‘History of Humanism’ feature at TheHumanist.com, is a regular contributor to Free Inquiry and New Humanist, and is the co-writer of the twice-weekly history and philosophy webcomic Frederick the Great: A Most Lamentable Comedy.

Further Reading

What Should We Do with Our Brain? (2004) is Malabou at her most enthusiastic and expansive – full of the hope of neural plasticity’s promise to save the world. This book is also easily her most readable. More recently, Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity (2009), and Self and Emotional Life (2013), have moved to more solid ground in the exchange between philosophy and science, so these are the books to read if you want to see the real promise of her synthesis, even though they are far less readable. They are, basically, the same book, with Self offering a second section authored by Adrian Johnston on why psychoanalysis might not be in as much trouble as Malabou supposes.

The neuroscientific material that she pulls the most often from is Joseph LeDoux’s excellent The Synaptic Self (2004) – an incredible account of the formation of the brain and the role that synaptic variation plays – and Antonio Damasio’s Looking for Spinoza (2003) and Descartes’ Error (1995), both of which engage with the classical philosophical tradition from the perspective of neurology.