Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Hegel Reading Heraclitus

Antonis Chaliakopoulos offers an intro to Heraclitus, and to Hegel, via each other.

When Euripides asked Socrates his opinion on the book On Nature by Heraclitus of Ephesus (c.535-475 BC), Socrates answered that the part he understood was excellent, as was the part he did not.

These are the two faces of Heraclitus. On the one side is the obscure philosopher, the ‘Dark Riddler’ whom even Socrates had trouble comprehending. On the other side is the profundity of a work worth exploring, a work that is rewarding in its depth. This duality is expressed in the lyrics of the ancient tragical poet Scythinus:

“Do not be in too great a hurry to get to the end of Heraclitus the Ephesian’s book: the path is hard to travel.

Gloom is there and darkness devoid of light.

But if an initiate be your guide, the path shines brighter than sunlight.”

(Diogenes Laertius IX, 16)

Hard and rewarding is Heraclitus, but also mystical, since an initiation into his work by an acolyte is required. In this regard, G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) is similar: an undoubtedly difficult, often inaccessible philosopher, whose secrets can best be revealed through a proper introduction.

Hegel himself also felt the attraction of Heraclitus. That is made explicit in Hegel’s Lectures on the History of Philosophy (1830), where he notes: “Here we see land; there is no proposition of Heraclitus which I have not adopted in my Logic” (trans. E.S Haldane, p.278). However, Hegel’s reading of Heraclitus in his Lectures is not that of a historian studying a historic persona; it is a tribute to a spiritual predecessor to whom the foundations of his own philosophy can be traced.

One problem with this spiritual descent is that it entails a lot of anachronistic speculation. It is very doubtful that Heraclitus really meant things the way Hegel interpreted them. Moreover, the work of the Ephesian today survives only in fragments retrieved from the works of Greek, Roman, and Christian authors who also often distorted the meaning of the original. Hegel doesn’t really tackle this issue at all, and often takes the fragments out of their original context, offering at best ambiguous interpretations.

Yet despite the issues of how he interpreted the fragments, Hegel’s lecture on Heraclitus conceives the spirit of the Greek philosopher in a unique manner. Behind the multiple layers of Hegel’s ideas, the Heraclitean logos (λόγος) or ‘divine principle of reason’ still shines brightly. Furthermore, Hegel was one of the few, if not the first, Western philosopher in centuries to properly understand the Heraclitean principles of constant flux and the unity of opposites, which ideas also form the basis for Hegel’s dialectic. This means that Hegel’s lecture on Heraclitus is a good introduction to the Greek’s most complex concepts, and an even better introduction into Hegel’s own philosophy. This is akin to the way Homer’s epics are more useful in understanding Homer’s own time than understanding the later Greek Bronze Age they were read in, in which they were already regarded as ‘classics’.

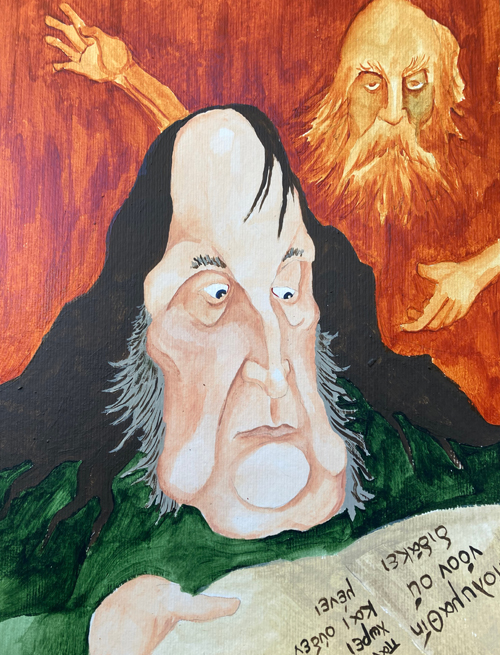

Hegel reading Heraclitus by Stephen Lahey 2021

Heraclitus According to Hegel

‘Dialectic’ means an interpretive process incorporating contradictory ideas to reach a conclusion. Let’s look first at dialectic as Heraclitus uses it.

The dialectical method is comprised of three moments. In the first, the ‘moment of understanding’, one idea (for example, Being) is firmly defined. In the second moment, called ‘the dialectical’, we pass on to the completely opposite idea (Non-Being). The third moment is the ‘speculative’, and it leads to a understanding of the unity of the two previous ideas, which are now reconciled (in this case, in Becoming).

Heraclitus’s dialectic is a positive one: it does not aim at proving what does not exist (like the Eleatics), or that all opinions are relative (like the Sophists). Instead it searches for what exists, what is true. Hegel credits Heraclitus with conceiving the developed dialectic form. According to Hegel, Heraclitus was the first to formulate that the ‘Absolute’ – the all-inclusive whole or unity that underlies everything – exists in the unity of opposites, first as a ‘Being’, and secondly as a constant ‘Becoming’. The main philosophical adversary of Heraclitus was Parmenides. Against Parmenides’ aphorism that ‘‘the one… is, and it is not possible for it not to be’’, Heraclitus believed that everything is in flux – that everything is Becoming – and so in a certain sense what is, at the same time, isn’t.

For Hegel, with Heraclitus, philosophy reaches the high plateau of ‘speculative form’ – a kind of thinking that is able to explain everything without gaps. For him, previous thinkers, such as Parmenides and Zeno dwelt with an ‘abstract understanding’ of, presumably, lower value. Additionally, Hegel thinks that Heraclitus is unjustly called obscure. Given that complex language is needed to describe complex ideas, Heraclitus is instead a master of complex concepts. Those unable to fully grasp them confuse complexity with obscurity in order to justify their own failure in understanding. Here, Hegel again invokes Socrates’ saying that ‘it would take a Delian diver’ to get to the bottom of Heraclitus; the process reminds him of fishing for pearls.

The Logical Principle

For Heraclitus, two opposing things unite in one to create harmony, and everything that exists is constituted through the struggle of its opposing parts. This is expressed in multiple fragments of his writing, such as the following:

“Men do not know how what is at variance agrees with itself. It is an attunement of opposite tensions, like that of the bow and the lyre”

(B51, trans. T.M. Robinson, 1987).

Another formulation of this principle is found in his statement that honey tastes sweet to the healthy and bitter to the sick. In this case, honey is one thing with two opposite qualities, just like seawater is both death for humans and life for fish: “The sea is the purest and the impurest water. Fish can drink it, and it is good for them; to men it is undrinkable and destructive” (B61).

Interpreting these fragments, Hegel deducts that “the truth only is as the unity of distinct opposites and… of the pure opposition of being and non-being… Being is and yet is not” (Lectures p.282). This is the primary Hegelian logical principle (his version of the logos): the unity of Being and Non-Being which together constitute ‘the Absolute’. Furthermore, in Hegel’s Science of Logic (1816), after a first examination, pure Being and pure Non-Being are found to be notions void of meaning if viewed independent of each other (§132-134). Instead, it is only in terms of the transition from a state of nothingness to a state of existence that they can both be properly defined and understood. This movement from one state to another is Becoming. This is the only constant, and it is becoming which logically synthesizes nothingness and existence.

The principle of constant movement, of Becoming, is also key in understanding Heraclitus. Plato encapsulates it perfectly in his dialogue Cratylus (402a): “Heraclitus says, you know, that all things move, and nothing remains still and he likens the universe to the current of a river, saying that you cannot step twice into the same stream.” But the most famous examples, by far, are Heraclitus’ own river aphorisms:

“You cannot step twice into the same river; for fresh waters are ever flowing in upon you.” (B12)

“We step and do not step into the same river; we are and are not.” (B49a)

The world is in flux, nothing remains the same, everything is changing, everything is becoming: Panta rhei – ‘Everything flows’ – is the philosophy of Heraclitus concentrated in two words. This constant movement of Being requires the activity of Being dividing itself into opposites that are both distinct entities and parts of Being.

In his lecture on Heraclitus, Hegel takes these ideas a step further to explain identity. Subjectivity is the opposite of objectivity, and since “each is the ‘other’ of the ‘other’ as its ‘other’, we here have their identity.” The point is that without the ‘other’ and its implications there is no subject, since the subject can only be defined by something other than itself. So the identity of a thing is the result of a dialectical process. This is exactly why in the Phenomenology of the Spirit (1807, Φ 178) Hegel writes that self-consciousness exists only by being recognized by another self-consciousness. But this illustrates well how for both Heraclitus and Hegel the universe is not definite and stable but moving and changing. Being is a process – that of Becoming.

Time & Fire

The German goes on to interpret two more basic Heraclitean concepts: time and fire.

Time for Heraclitus is the very embodiment of Becoming, and its first form. It is pure Becoming, and the harmony of the opposing Being and Non-Being. Hegel opines that “in time there is no past and future, but only the now, and this is, but is not as regards the past; and this non-being, as future, turns round into Being” (Lectures, p.287).

For Heraclitus, fire is the elementary principle out of which everything is created and to which everything returns. It can take the shape of everything and everything can take the shape of fire, in a process of continuous creation and destruction. Hegel argues that Heraclitus didn’t really believe that everything is made from fire in the way that Thales thought that everything came from water; rather, he chose fire as a metaphor of a force that constantly shifts its form. Fire never stays still and is always in unrest. Unlike earth, air, or water, which often appear static, fire is itself a process. In these senses, fire can be viewed as representing the idea of Becoming in terms of the natural process of material transformation – as opposed to time, which is the abstract representation of the process.

The natural processes represented by fire destroy and create matter. These are two distinct paths; indeed, in Heraclitus we encounter a ‘way downwards’ (ὁδός κάτω), where fire becomes moisture, which then becomes water, which then condenses to become earth; and a ‘way upwards’ (ὁδός ἄνω), where earth becomes water, then water gives form to everything else. Like everything else, this is a process that never ceases. Hegel says that the way upwards is the process of differentiation and creation that leads to Being; and the way downwards is the process of destruction, leading to Non-Being. “Nature is thus a circle” concludes Hegel.

Heraclitus portrait © Clinton van Inman 2021 Facebook at Clinton.inman

Consciousness & Truth

Expressing his admiration for Heraclitus’s ability to explain the dialectic using simple analogies drawn from daily life, Hegel says that he has “a beautiful, natural, child-like manner of speaking truth of the truth” (p.293). There’s something deeply entertaining in reading one of the most incomprehensible philosophers of all time claiming that Heraclitus, a.k.a. ‘the Obscure One’, has a ‘child-like manner’ of speaking the truth. Hegel also sees in Heraclitus the origins of other concepts central to his system of thought, such as the unity of object and subject, the omnipresent nature of the Absolute Spirit (Geist), and the unity of experience. These ideas are thoroughly explored in the third section of his lecture, which answers the questions: ‘How does logos come to consciousness?’ and ‘How is it related to the individual soul?’ Hegel believes that the Greek rejected sensuous reality as the area where one can find the truth. If for Heraclitus everything that is also is not, that means that all we observe as real is also not real. Following this path, Hegel concludes that “not this immediate Being, but absolute mediation, Being as thought of, Thought itself, is the true Being” (p.294). In other words, it is not through observation, but only through reason, that one can discern the truth.

Hegel gives another interesting interpretation to some Heraclitean fragments about sleep, learning, and reality:

“All the things we see when awake are death, even as all we see in slumber are sleep.” (B21)

“Eyes and ears are bad witnesses to men who have barbarian souls.” (B107)

“The learning of many things teacheth not understanding, else would it have taught Hesiod and Pythagoras, and again Xenophanes and Hekataios.” (B40)

Hegel interprets these fragments to show a distinction between particular and universal reason – between the thought of the individual (or subjective consciousness) and the Idea (objective or Absolute consciousness) or as Heraclitus names it, the logos. ‘Consciousness’ here refers to cognitive awareness, and it is often used interchangeably by Hegel to denote both the subject’s consciousness of an object, and also the subject’s self-awareness. According to Hegel, Heraclitus first established the unity of the subjective and objective consciousness – a key Hegelian idea – when he implied that the waking man is related to things universally. Sextus Empiricus expresses some relevant ideas on this issue in Adversos Mathematicos, VII.127-133. Here he relates that for Heraclitus, sleep is a state where our senses, our anchors to the world, stop functioning. The subject stops communicating with the logos, the objective consciousness, and this isolation makes what we experience in our sleep a dream. The only connection with the world in this sleeping state is our breath, which is likened to a root keeping us attached to reality. In contrast, when we are awake, we establish a fragmented but real conscious relationship with reality and the logos. If Sextus correctly understands Heraclitus, Heraclitus is also rejecting those who claim to have received wisdom from God in their sleep.

In another fragment, Heraclitus seems to advocate that we can reach objective knowledge of the logos. This may appear to go against his doctrine of constant flux, which implies that empirical knowledge is meaningless since things change all the time. However, here Heraclitus advocates using changing empirical observations to come to an unchanging knowledge of reality:

“Though this Word [Logos] is true evermore, yet men are as unable to understand it when they hear it for the first time as before they have heard it at all. For, though all things come to pass in accordance with this Word, men seem as if they had no experience of them, when they make trial of words and deeds such as I set forth, dividing each thing according to its kind and showing how it truly is. But other men know not what they are doing when awake, even as they forget what they do in sleep.” (B1)

Commenting on this fragment, which is thought to be the introduction to Heraclitus’s book, Hegel says (pp.296-97):

“Great and important words! We cannot speak of truth in a truer or less prejudiced way. Consciousness as consciousness of the universal, is alone consciousness of truth; but consciousness of individuality and action as individual, an originality which becomes a singularity of content or of form, is the untrue and bad. Wickedness and error thus are constituted by isolating thought and thereby bringing about a separation from the universal. Men usually consider, when they speak of thinking something, that it must be something particular, but this is quite a delusion.”

Hegel concludes his lecture on Heraclitus with a modification of the words of Socrates he used for his introduction:

“What remains to us of Heraclitus is excellent, and we must conjecture of what is lost, that it was as excellent. Or if we wish to consider fate so just as always to preserve to posterity what is best, we must at least say of what we have of Heraclitus, that it is worthy of this preservation.”

© Antonis Chaliakopoulos 2021

Antonis Chaliakopoulos is an archaeologist from Athens interested in the reception of classical art and philosophy.