Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Fiction

Who’s Watching Who?

Grant Bartley tells a terrifying tale of privacy, paranoia and popular culture.

Phil and Sarah are in their small living room, slumped on their once-cream beige sofa, watching rolling news clips. Sarah glances around and thinks, ‘How can I feel so bored and let-down already? Talk about being ground down by disappointment through failed expectations. Except we don’t talk about it.’ She says, “So how can we remake our lives, Phil?”

“I dunno. To start, maybe think up something nice to do.” He purses his lips.

“No!” She hits his arm with a cushion. “I mean, how can we really make things better for ourselves, rather than pursue luxuries that we can’t afford anyway?” She gestures vaguely at the screen as a Jaguar advert flashes up.

Phil mumbles his usual reply: “By turning this off, for a start. By looking at the world. Unfortunately, reality doesn’t have the cachet of the screen world. Reality can’t compete with the glamour and wealth we yearn for.”

“What do we do, then? Not just us, I mean Society?”

“Give everybody food and shelter and education and entertainment, would be my personal preference. That’s what I’d do. I can’t see it happening though. So my question is, What is to the ultimate benefit of the human race? By which I mean, well, me, primarily – but everyone else too,” he added, generously.

“Your benefit and the world’s benefit are two different things,” Sarah points out, “And what you mean by ‘benefit’ depends on the situation you’re talking about anyway. What’s good for you to do at one time is not good for you at another, nor for another at the same time. Same goes for what’s good for humanity…”

“Maybe there are some principles of good life which are always true?”

“Is that what you’re asking? What’s beneficial to people at all time, forever?”

In a now-rare moment of intimacy, Phil turns away from the screen to face Sarah’s face, and really look at her while he’s talking to her: “I really do want to see a better world created,” he asserts, “But I’m not sure we’re going about it the right way, as a society. Especially given the vast misdirection we call popular culture. We can’t trust the opinions of people who produce that!” He sniffs: “Where’s the self-awareness?”

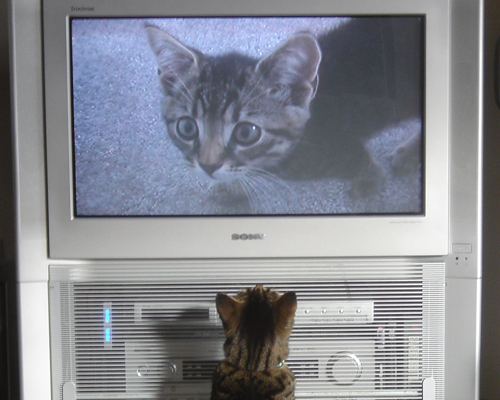

Cat watching TV © cloudzilla 2004 Creative Commons 2.0

“Yeah. I do know what you mean, for sure. Like I’m free to go and vote on what the right way to live is, when I’ve already been thoroughly and persuasively informed what the right way to live is, and hence how to vote, by the media.”

Phil thinks that’s not at all what he meant, but he responds, “I guess my basic question is, how do we know what world we want to create anyway? What’s our source of information about that?”

“Those are vital questions, aren’t they?” agrees Sarah, turning back to the screen.

“I think so. If we don’t understand what we think or why we think it, then we don’t understand anything. I wholeheartedly agree with you and the philosophers about that” said Phil, portentously.

“Or is it our definitions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ we should be most worried about?” asks Sarah, who has taken an ethics course, and knows intimately how language can distort the truth – particularly when you don’t know clearly what the words imply.

“No. I mean, I was just saying –” Phil is sick of Sarah pretending she’s listening to him; but now he’s lost the thread of his thoughts too. He continues randomly, “Don’t trust anything anybody tells you if you don’t have to, that’s all I mean… What do you mean, anyway? ‘Who controls our opinions?’?”

“That’s the question, isn’t it?” Sarah replies; then she remembers that she’s talking to an occasionally child-level intellect. She changes tack, looking for a way to explain her fears about power in a humorous and non-threatening manner to him. “What colours would you choose for your global police force?” she asks Phil. “Black blue, or brown, do you think?”

“It wouldn’t be my global police force. I don’t want one!”, Phil responds, sipping from his can of Tennent’s. He is only mock indignant. They’re running this grim in-joke about the balance of power in world politics and what to do about it. He has often predicted the emergence of police states. Hopefully not everywhere simultaneously, though.

Sarah tries to explain her intuition. “You know what it means if we’re right, Phil?” she asks, then self-corrects, “I mean, if I’m right, that we’re programmed in our thinking by the media? It means we’re there now! I mean mind massage! I’ve just put it all together…” Her voice has abruptly changed tone, from playful to shock: “Don’t you understand? We’re already there. We’re living in an authoritarian state, Phil,” she says, prodding him.

She’s right to some extent. A van parked down the street contains three men in matching boiler suits (all ex-Strathclyde police, curiously). They’re waiting for evidence of hate speech or extremism, especially from Phil or Sarah, who are known expressers of politically incorrect views. Following information received from big-eared neighbours with thin walls and cavernous imaginations, for two weeks now audio from the mic of Phil’s smartphone has been fed straight to an AI assessment app, which has flagged copious evidence of the sedition of the inhabitants of no.73. Their inflammatory words could be played to a judge, if that were ever to become necessary (“But only if you want to kill him with boredom,” the tech guy remarked cynically).

“Yes. I forget sometimes how much we’re programmed by this thing,” Phil agrees sagely, gesturing at the hungry screen at the centre of their lives. “Forget Orwell’s police-state paranoia, we’re controlled through status desires. I absolutely hate that!”

‘That’s a good line,’ he thinks, ‘Pretty major’. So he repeats it: “The world is now being controlled through social status. I mean, no-one can escape wanting respect, can they? So channelling peoples’ desires for status and controlling access to it has to be an infallible means of control, hasn’t it? We think it’s just market forces and media but we’re being manipulated, I’m certain of it. Don’t you see that?”

“I’m sorry, you’ve lost me,” Sarah replies. She forgets mind-control for a moment, instead trying to think how to file this conversation in her inventory of Phil’s character, simultaneously trying to remember if they’ve already had this talk. She does remember this conversation, or something like it, at least. So she repeats the conclusion she thinks she remembers arriving at then: “Oh, I remember now! We’re not gonna take it anymore! And of course we need to get out of here, darling,” she adds, smiling, waving vaguely around the small room. “It isn’t big enough for us, is it really, after all? Especially when Travis is staying with us.” Travis is her son.

Phil sighs and raises his voice, mimicking optimism: “What do we know about the future, though, anyway? Maybe we will be rich!”

“Yeah. Eventually, maybe. Yeah.”

Phil’s response stumbles down into a mutter: “It’s sucking me in, too, Sarah – like, normal desires and responsibilities. Can’t we see what we’ve become? We’re programmed potatoes!” For a few seconds Phil becomes statuesque in his silence. Glimpsing a depressing prospect ahead of him for the rest of his life, he thinks, ‘We sell our passion and romance with life out to the networks that keep us entertained. And they’re just the first line we must fight against to avoid sinking into materialism with the cement shoes of our desires. Man, I don’t think I’m winning against the world here…’ Phil is becoming so angry with the apparent immediate target of this arrow of thoughts, the screen in front of him, that his brows furrow as he glares at it. He asks tensely, “Where do we get our information about what to expect in life anyway, Sarah?”

Sarah nods at the screen, then tosses a glossy magazine at him for emphasis. “That’s exactly what I’m saying,” she says. As she speaks, one of the boiler-suits discreetly breaks a small pane on the back door, before leading his colleagues quietly down the hallway. “But the sorry truth is, the world isn’t interested in hard questions anymore.”

“The world isn’t safe for hard questions anymore,” Phil replies. “It’s a bad sign for freedom and the future, right?”

He reflects, ‘I knew I’d get stuck in the vortex of normal life eventually. Now it’s finally happened. Big financial expectations come with marriage. How boring the predictability of it all. Domesticity is as inevitable as the instinct to love, and as big a disappointment too. Disappointing to know that the flower of our love is dying of tedium. Our love, not just for each other, but for life; the world. We’re living examples of the petrification of hope, as despair spreads its shadow across the globe.’

“Things aren’t looking good,” Sarah agrees, nodding, glancing at the news on the screen.

© Grant Bartley 2024

Grant Bartley is Editor of Philosophy Now magazine. More of his short stories can be found at https://tinyurl.com/Bartley2024.