Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Tallis in Wonderland

Atomism & Smallism

Raymond Tallis wonders what the world is made from.

There is a much-quoted passage near the opening of Richard Feynman’s famous Lectures on Physics (1963):

“If in some cataclysm all of scientific knowledge were to be destroyed, and only one sentence passed on to the next generations of creatures, what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words? I believe it is the atomic hypothesis (or the atomic fact, or whatever you wish to call it) that all things are made of atoms – little particles that move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another.”

These ‘little particles’ have undergone some strange transformations in the last century, not least as a result of Feynman’s own work. They have become ever more ethereal, ceasing to be self-standing nanoscopic corpuscles bumping into one another. According to the interpretation now accepted by many physicists, they are quantized waves in fields of force that spread out through space and time. At any rate, atoms seem no longer to be discrete solid entities, separated by what Democritus, the first atomist, called ‘the void’. Nor are they indivisible – though this is exactly what, etymologically, the term ‘atom’ (atmos) means. According to modern physics’ Standard Model, the physical world is divisible into seventeen kinds of sub-atomic particles. (It is a nice irony that the ‘Atomic Age’ began precisely when it was recognized that atoms were not atmos.) And the story of the deconstruction of the atom, we may be sure, hasn’t ended yet.

Since quantum entanglement has cancelled discreteness and atomic fission has put paid to indivisibility it might appear that the ‘atomic hypothesis’ no longer carries the implication that the fundamental constituents of matter are discrete and indivisible. If so, it is difficult to say what “everything is made of atoms” does mean. One could be forgiven for thinking that Feynman’s mantra that ‘all things are made of atoms’ needs to be qualified by adding “though we don’t know what atoms themselves are made of, nor, judging by our present performance, are we likely to.”

Does this mean that atomism boils down to an empty truism: that everything is made of whatever everything is made of? This hardly seems likely, given the staggering heuristic power in physical science of the ‘everything is made of atoms’ idea. What then remains of atomism?

Boiling Up & Down

Two metaphysical claims seem to have survived successive paradigm shifts in physics. The first is that at the fundamental level there is homogeneity or uniformity. The second is that reality at that level is not formless gunk. Importantly, there is a connection between these two aspects of smallism, according to which pebbles, chaffinches, and readers of Philosophy Now, have the same ultimate constituents, and those constituents, if they are in any sense discrete, are very, very, very small.

Let us first look at uniformity. It is counter-intuitive. If what-is boils down to microscopic sameness, how does it boil up to macroscopic difference? At the very least, the idea seems to demand an explanation as to how it is that our everyday world is populated with entities as varied as thoughtless stones and thoughtful citizens. What’s more, the lack of qualities – notably secondary (sensory) qualities, such as colour, smell, the feeling of warmth – at the atomic level and lower, makes the widespread presence of those qualities in the world we inhabit inexplicable. What is it, then, that makes the idea that there must be uniformity at the most fundamental physical level so attractive?

In part it’s based on the truism I mentioned earlier: ‘Everything is made of whatever it is that everything has in common’. For entities to qualify as basic constituents, they must be constituents of whatever else exists. A ‘Theory of Everything’ will necessarily exclude anything that’s not shared by Everything. It is not to be unexpected that the instances of types of fundamental entities (which are now subatomic) are identical with one another, since any discovered difference between members of a type is a signal to dig deeper, perhaps to propose more fundamental entities. These homogeneous, more fundamental entities then would have the status of the basic constituents of matter. The Theory of Everything, therefore, will necessarily be located at a level at which everything is like everything else (plus, perhaps, the void).

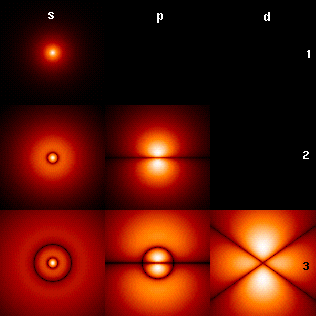

Electrons in clouds around atomic nuclei

© FlorianMarquardt 2002 Creative Commons

This brings us to the second, still surviving, feature of (post-) atomism: the ‘smallestness’ of these ultimate constituents. Even whole, unsplit atoms are minute. There are close on 1028 of them in the body of your columnist.

This unimaginable smallness is no accident. The smaller the entities, the less room there is for qualitative variety. So if ultimate reality is to be identified with what everything has in common, it must be close to being featureless. These sub-atomic entities, being the smallest possible entities, have minimal variation. The ‘charm’ and ‘colour’ of so-called ‘charmed’ and ‘coloured’ quarks, for instance, are strikingly charmless and colourless. Ditto ‘spin’ and ‘charge’. The quality that entities at the ultimate level of being have in common is lack of qualities.

The near-featurelessness evident at the fundamental level reaches its culmination in the reduction of what exists to a mathematical model. The final step to the mathematization of sub-atomic reality is the conflation of two claims:

1. That the elementary entities can be fully described by mathematical formulae;

2. That those entities are mathematical structures.

Unfortunately, this deepens the puzzle as to how, if the material world boils down to featureless ingredients, it then adds up to entities as different from one another as pebbles, chaffinches, and readers of Philosophy Now.

Out of the Depths

‘Real’ atomists might argue that, to the contrary, without discrete pieces on the board, able to be arranged in different ways, there would be no basis for the variety of things we see in the world. If the stuff of the universe was at bottom formless gunk, such composition could not take place. Hence the problem of the claim that the universe is a single wave function – which would suggest that it is gunk all the way down, and, indeed, all the way up. (We shall return to this.)

Even so, it is not clear that various arrangements of uniform fundamental parts could generate the kinds of variety we see in our world. Nevertheless, there seems to be some case for ‘smallism’:

a) That which is truly fundamental is that which is most real: atoms, or whatever we end up calling the ultimate constituents, are more real than chaffinches.

b) That which is fundamental must lack properties which distinguish it from other entities at the same level.

c) That which is smallest has least scope for variation, and is therefore closest to being featureless.

The minute subatomic ultimate constituents of atoms will meet these criteria, and hence are both most universal, and homogeneous. So whence the rich variety of the world in which we live? Although the ultimate wave-particles are homogeneous, they can give birth to heterogeneity by being gathered up in different quantities in different ways, just as uniform bricks can be combined in different ways to create fundamentally different buildings; or just as subatomic wave-particles can be combined to create atoms with different properties, and those atoms can be combined variously to generate the almost limitless variety of chemical compounds, with all their distinctive properties.

Does combination, then, solve the problem of how, if everything boils down to nearly featureless subatomic entities, we can explain the origin of the richly-featured world in which we live and have our being and in which physicists practise their physics? Does it explain the emergence of macroscopic variety out of nanoscopic monotony?

Unfortunately, the very idea of combination creating heterogeneity out of homogeneous constituents has become problematic.

Firstly, our ordinary notions of space and of time are under (further) threat from developments in contemporary physics. Indeed, the entangled universe of quantum mechanics has suggested to some that the totality of things is a single indivisible unity. According to Heinrich Päs, “All objects in existence” are “encoded in a universal wave function that describes a single, entangled state” (The One: How an Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics, 2023). Far from everything being made of discrete atoms combined in various ways, then, the universe is a single quantum whole.

Secondly, we have to explain the ascent of scale from the nanoscopic world to the macroscopic one. As I discuss in my book Freedom: An Impossible Reality (2021), there are good reasons for thinking that scales are not inherent in the physical universe away from minds: rather, scales are dependent on the grain of attention of conscious subjects. For some, this undermines the assumption that the ultimate truth of what is will be found in its smallest components, and justifies their suspicion that ‘fundamentality’ is not a natural property, and that ‘fundamental entities’ are not natural kinds – or no more so than pebbles, chaffinches, and readers of Philosophy Now.

The idea that the reality is to be found in its fundamental constituents was enjoyably mocked by Larry Wright in ‘Rival Explanations’ (Mind 82, 1973). Wright imagines a person who, having examined the list of ingredients on a carton of milk and, not finding ‘milk’ in the list, concludes that the carton contains no milk, and that there must be another carton which contains the milk. Smallism seems vulnerable to this argument. If we embrace the idea that everything is made of subatomic wave-particles, or whatever is regarded as the most fundamental physical constituents, we have only the constituents, and not whatever they constitute.

Some smallists may respond by suggesting that the macroscopic world of heterogeneous entities is an illusion. If, however, this were the case, it would be difficult to know where the illusion came from. The universe would be a desert of (true) atoms – though in the absence of a viewpoint on it, it would not even be gathered up into a desert. Even less would that desert then bloom into an illusory world.

And so we say farewell to the belief that even if ‘everything is made of (sub-)atoms’, then that’s the level where ultimate reality lies. While smallism is necessary to defend the idea that there are simple laws and properties that encompass everything, it does not follow that it’s the whole story of what is.

Small, it is said, is beautiful. But beneath the atomic level, it is not even ugly. It is close to being featureless, so that it can take its place in the Theory of Damn Near Everything. Such a theory runs the danger of being The Theory of Nothing in Particular – and that may not be clearly distinguishable from A Theory of Nothing.

A story, perhaps, for another day.

© Prof. Raymond Tallis 2024

Raymond Tallis’s Prague 22: A Philosopher Takes a Tram Through a City will soon be published in conjunction with Philosophy Now.