Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

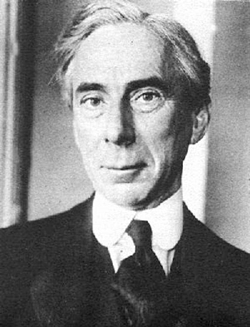

Bertrand Russell Stalks The Nazis

Thomas Akehurst on why Russell blamed German fascism on German philosophy.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) is best known for his activities at the very beginning and at the very end of his working life. His philosophical reputation was made by his pioneering insights into logic in the first decade of the twentieth century, and he cut his political teeth through his pacifist opposition to World War I – an opposition which saw him jailed for spreading rumours harmful to the alliance between Britain and America. Forty years later, as an old man, he helped found the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the late 1950s. These facts, plus his brief flirtation with polyamory, which scandalized conservative elements in Britain and America, tend to be what we know about him. What is less well known is that in the 1930s and 1940s Russell’s attention turned to the idea that the origins of Nazism were primarily philosophical. I want to argue that this account of the origins of Nazism helped to shape the hostility to continental philosophy which ran, and in some quarters still runs, through analytic (‘Anglo-Saxon’) philosophy.

The Philosophical Tide Turns

The story of Russell’s philosophical account of the evils of German politics starts with the chaotic jingoism of the First World War. Prior to 1914, German scholarship had been widely respected in Britain. However, as nationalist rhetoric intensified, and German Shepherd dogs were shot in British streets, German philosophy too came under increasing fire. In his The Metaphysical Theory of the State published in 1918, L.T. Hobhouse wrote this about witnessing a Zeppelin raid on London:

“Presently three white specks could be seen dimly through the light of the haze overhead, and we watched their course from the field. The raid was soon over… As I went back to my Hegel my mood was one of self-satire. Was this a time for theorizing or for destroying theories, when the world was tumbling about our ears? … In the bombing of London I had just witnessed the visible and tangible outcome of the false and wicked doctrine, the foundations of which lay, as I believe, in the book before me.”

(Quoted in Thomas Baldwin, ‘Interlude: Philosophy and the First World War’ in The Cambridge History of Philosophy 1870-1945, 2003, p.367.)

Hobhouse was not alone. Many British philosophers thought that they saw the root causes of the First World War in German nationalist philosophies of the nineteenth century, most particularly in Hegel. Friedrich Nietzsche was the other popular target. A bookseller on the Strand in London announced in his window that this was ‘The Euro-Nietzschean War’, and urged passers-by to “Read the Devil, in order to fight him the better.” (Quoted in Nicholas Martin, ‘Fighting a Philosophy: The Figure of Nietzsche in British Propaganda of the First World War’, The Modern Language Review 98, no.2, 2003, p.372.)

Bertrand Russell

Russell was a witness to the peculiar spectacle of the British public turning on German philosophy during World War I, but did not make any moves to join the general condemnation. All of this changed in the early 1930s, when in an article called ‘The Ancestry of Fascism’ in his In Praise of Idleness (1935) he resurrected the argument that German philosophy lay behind German political aggression. Following the lead set by Hobhouse and others in the First World War, Russell argued that while Nazism could be accounted for partially through political and economic factors, at its heart lay a philosophy that emerged from trends in nineteenth century thought. Although during the First World War there had been principally two villains, Hegel and Nietzsche, Russell managed to find a whole family tree of Nazism’s ancestors: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Immanuel Kant, G.W.F. Hegel, Johann Gotlieb Fichte, Giuseppe Mazzini, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Heinrich Von Treitschke, Thomas Carlyle, William James and John Dewey! This rogues gallery of philosophical forebears of the Nazis is a fairly diverse one, encompassing two Americans (James and Dewey), a Swiss (Rousseau), an Italian (Mazzini), and an Englishman (Carlyle); but by far the largest grouping are the Germans. Russell was convinced that the concentration of this (allegedly) proto-fascist philosophy in Germany was no mere historical accident, since Germany was always more susceptible to Romanticism than any other country, and so more likely to provide a governmental outlet for this kind of anti-rational philosophy (see p.752 of Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy, 1946). So the appearance of the National Socialist movement in Germany rather than elsewhere was for Russell entirely predictable, since to him the Germans had a psychological weakness for this kind of philosophy. The Brits by comparison appear relatively immune – only Carlyle makes it onto Russell’s list of the philosophical precursors of fascism; and he, Russell points out, belongs in the German tradition, being a disciple of Fichte.

Bad Philosophy

What were all these men guilty of according to Russell? They all espoused philosophies that promoted proto-fascist politics. Russell suggested that, for instance, Hegel’s conception of freedom “means the right to obey the police and it means nothing else at all” (ibid) – and so is perfectly attuned to totalitarian politics. Meanwhile, Hegel’s doctrine of the state, “if accepted, justifies every internal tyranny and every external aggression that can possibly be imagined” (History, pp.768-9). Furthermore, Nietzsche’s aristocratic ethics led to a moral case for the eugenic eradication of the ‘bungled and botched’ – non-noble people, to whom no value therefore attaches. Russell also saw Nietzsche contributing to the store of ideas his loathing for democracy and his ‘gleeful’ prophecy of future wars (History, p.791). But Russell was not content to just condemn the apparent politics of his rogues’ gallery; he wanted to make clear that this bad politics emerges from bad philosophy. This claim is well summed-up in A History of Western Philosophy: “A man may be pardoned if logic compels him regretfully to reach conclusions which he deplores, but not for departing from logic in order to be free to advocate crimes” (p.769). This comment is aimed at Hegel, but it is precisely what Russell accuses many of the supposed ancestors of Nazism of doing – of leaving behind good argument in order to promote barbarity.

This view sits slightly uncomfortably with a rival interpretation Russell offers of the argumentative failings of the proto-Nazis. Sometimes he seems to imply that they do not deliberately make bad arguments, but rather that they are so philosophically inept that they cannot help but make bad arguments. So Russell also says of Hegel, for example, that in order to arrive at his philosophy you would require a lack of interest in facts, and “considerable ignorance” (p.762). He also claims that “almost all Hegel’s doctrines are false” (p.757).

Whether the diagnosis is incompetence or deception, the force of Russell’s critique of these thinkers is that their philosophical contributions are of a painfully low quality. Sometimes Russell is content simply to assert this; at other times he seeks to provide arguments demonstrating the absurdity of their views. This is an early attempt to dismiss Nietzsche’s ethics: “There is [in Nietzsche’s argument] a natural connection with irrationality since reason demands impartiality, whereas the cult of the great man always has as its minor premise the assertion ‘I am a great man’” (History, p.757). Russell’s claim here is that to believe, as Nietzsche did, that only a small number of humans are of any value must imply that you believe yourself to be one of those humans. But, Russell claims, this is a failed argument, because the assumption involved, that ‘I am a great man’, may well be wrong, and in any case, has not been arrived at in an impartial way.

It is a striking feature of Russell’s attempts to show that these philosophical ancestors of fascism can’t make good arguments that in the course of doing so he makes so many poor arguments himself. This argument against Nietzsche is a clear example: there is absolutely no reason why someone who believes that only a few people are of value must believe that they themselves are amongst those people. Many who believe in the aristocratic ethics may include themselves among the elect; but there is no reason why this must follow. In fact, the very notion of ‘hero worship’ implies a veneration for someone else for their having heroic qualities we do not possess.

Matters become more surreal yet in A History of Western Philosophy, as, reaching around for a more telling argument against Nietzsche’s ethics, Russell has the Buddha condemn Nietzsche for being a bad man. The anachronistic dialogue between ‘Nietzsche’ and ‘the Buddha’ is rounded off by ‘Nietzsche’ claiming that ‘the Buddha’s’ world of peace would cause us all to die of boredom. “You might,” the Buddha replies, “because you love pain, and your love of life is a sham. But those of us who really love life would be happy as no-one can be happy in the world as it is.” (History, p.800.) As we can see, this dialogue ends with the ‘Buddha’ rather implausibly insulting Nietzsche’s character. The ‘Buddha’s’ line of argument against Nietzsche here is remarkably similar to Russell’s own: elsewhere Russell accuses Nietzsche of being insane, megalomaniac, and possibly having an unnatural relationship with his sister.

Condemned Without Evidence

There are several peculiarities in Russell’s characterisation of the supposed ancestors of fascism. We have seen some of his rather desperate attempts to prove that these ancestors are philosophically incompetent – attempts which often leave the reader more concerned about Russell’s argumentative standards than those of his opponent. But the story gets stranger. In his writings on this subject, Russell offers no evidence whatsoever that there is any historical relationship between the ideas of his lengthy canon of proto-fascist philosophers, and those of any actual fascists. For example, no evidence is offered that Hitler read Hegel. Nor is there any analysis offered of the Nazi state that would demonstrate that it at all corresponded to Hegel’s ideas. What kinds of ancestors of fascism are these thinkers, then, if there is no apparent relationship between them and the fascists? Yet this lack of evidence doesn’t prevent Russell from freely asserting very definite claims, such as, “Hitler’s ideals come mainly from Nietzsche” (Religion and Science, 1935, p.210) and “The Nazis upheld German idealism, though the degree of allegiance given to Kant, Fichte or Hegel respectively was not clearly laid down” (from Unpopular Essays, 1950, p.10). Worse, throughout his investigations into the ancestry of fascism, Russell continued to use the strongest possible terms of condemnation: the tenor of his work on Nazism is that philosophers like Nietzsche and Hegel were bad people who wanted bad things to happen, and would be generally pretty pleased with the Nazi’s performance. Rarely does he concede the possibility that if the Nazis were influenced by these thinkers, it was the result of misreading or distortion. He is content to allow the full blame fall on the shoulders of the philosophers.

So we have a blanket condemnation of a host of nineteenth century philosophers as originators of Nazism, based on what appears to be no evidence. Given such a slap-dash approach to the history of political thought, one would be justified in thinking that Russell’s colleagues would offer some sharp words of rebuke, or at the very least ignore his accusations. Instead, his accusations against his major targets were straightforwardly accepted by people who would go on to shape analytic philosophy for the rest of the twentieth century. Many of the most notable mid-twentieth-century British philosophers – A.J. Ayer, Isaiah Berlin and Gilbert Ryle, for example – lined up to agree that nineteenth century German philosophy was corrupt, totalitarian in its predilections, and in some way responsible for Nazism. Isaiah Berlin in his review in Mind even called Russell’s treatment of Nietzsche in A History of Western Philosophy – with insulting Buddha and all – ‘a distinguished essay’ (Mind 56, no. 222, 1947, p.165). But they had no more evidence of the guilt of these philosophers than did Russell.

Imperfect Philosophers

Why were such strong yet unsupported criticisms of fellow philosophers allowed to circulate as unquestioned fact within British analytic philosophy? Several factors seem to have been in play. There was the heightened nationalism caused by the war – a nationalism to which the philosophers turned out to be no more immune than non-philosophical citizens. There was the pervasive idea of the guilt of German philosophy, which was a legacy of World War I. There was also the belief, common amongst Russell and his analytic colleagues, that these continental philosophers were philosophically hopeless. Hegel, the wellspring of much of nineteenth-century philosophy, had, they believed, been decisively refuted by Russell’s close colleague G.E. Moore in the first decade of the century. So none of Russell’s analytic colleagues had anything invested in looking again at these condemned philosophers. This rich combination of philosophical and cultural factors were sufficient for them to simply accept that the German philosophical tradition was fascist. Thus Russell’s at-best eccentric condemnation of German philosophy was perpetuated both by many of his influential followers and through his best-selling A History of Western Philosophy. Shortly after the war, Russell’s intellectual disciples gained a powerful grip on the discipline of philosophy in Britain. So began an “active process of forgetting and exclusion” as David West writes in ‘The Contribution of Continental Philosophy’ in A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy (ed. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit, 1995, p.39). This process saw thinkers in what Russell identified as the proto-Nazi tradition excluded from philosophical consideration in Anglo-American universities. And although thinkers like Nietzsche and Hegel have subsequently made something of a comeback, the continued hostility among some analytic philosophers to so-called ‘continental philosophy’ is in part the legacy of Russell’s tarring of the originators of this tradition with the brush of totalitarianism.

This lost episode in the recent history of analytic philosophy raises again the old question of the value of philosophical education. Russell made his own views on this very clear at the end of A History of Western Philosophy:

“The habit of careful veracity acquired in the practice of this philosophical method can be extended to the whole sphere of human activity, producing, wherever it exists, a lessening of fanaticism with an increasing capacity of sympathy and mutual understanding. In abandoning a part of its dogmatic pretensions, philosophy does not cease to suggest and inspire a way of life.”

(A History of Western Philosophy, p.864.)

Yet Russell and his followers’ readiness to condemn their fellow philosophers for proto-fascism seems to rather undermine his claims for the salutary power of his own philosophical tradition. He and his highly trained, and in some cases brilliant, colleagues appear to have been no more immune to the nationalist atmosphere of the day than their fellow citizens.

© Dr Thomas Akehurst 2013

Thomas Akehurst teaches political philosophy for the Open University and the University of Sussex. His book The Cultural Politics of Analytic Philosophy: Britishness and the Spectre of Europe (2010) is available from Continuum.