Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

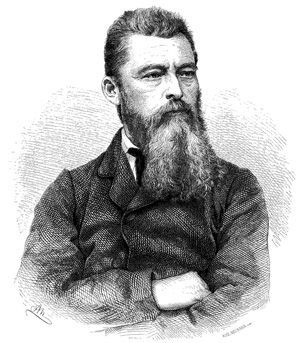

Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872)

Dale DeBakcsy tells us how Ludwig Feuerbach revolutionized philosophy and got absolutely no credit for it.

For many people, Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872) is the grey but necessary grit shoved between the foundation stones of Hegel and Marx in the edifice of modern philosophy. The phrase ‘transitional figure’ haunts Feuerbach literature as if he were little more than a just-functional MC holding the stage until the real act comes along. This is hardly a fair fate for the man whose critique of religion revolutionized philosophical theology, and who then pushed that critique into an all-out war against philosophy itself every bit as dramatic as the critiques of Marx and Nietzsche later in the century.

Feuerbach was born on July 28, 1804, in Landshut, Bavaria, into one of those large, broad-minded, and liberal German families that positively throve in the era before Bismarck. His brothers included a philologist, a mathematician, an archaeologist, and a jurist, so it is perhaps not too surprising that Ludwig would later make his name as a man whose watchword was the infinite potential and diversity of the human species.

Like many intellectuals of his time, Feuerbach arrived at philosophy via the gateway of theology. In 1823, he attended Heidelberg University as a student of religion, but was soon lured to Berlin and the big-stakes philosophy being wrought by Schleiermacher and Hegel, both lecturers there. Feuerbach was intoxicated by Hegel’s ability to explain his massive intellectual system in terms of mankind’s collective effort to understand itself. Even though he would spend most of his life passionately demonstrating the harm that Hegelianism does to humanity, Feuerbach would never entirely escape the spell of the great man’s thinking.

After five years of searching unsuccessfully for a permanent university post, Feuerbach fired off Thoughts on Death and Immortality in 1830 – a merciless, ironic, and downright fun broadside leveled at the Christian notion of personal immortality. You can hear him chortling while laying down lines like, “The entire pietistic or modern mystical theology rests only on a game of ball. The individual throws himself away only in order to have God throw him back again; he humbles himself before God only in order to be reflected in him. His self-loss is self-enjoyment, his humility is self-exaltation. He submerges himself in God only to surface again intact, and, refreshed and renewed, to sun himself in his own excellence.” This is classic Feuerbachian rhetoric – an incisive inversion of the accepted order aimed at bringing our loftiest notions of God back to their all-too-terrestrial origins.

This sort of critique of traditional religious thinking was incredibly dangerous to write in the increasingly reactionary atmosphere of the time, and so Feuerbach published it anonymously, which delayed, but did not prevent, the cold hammer of retribution from falling. After his authorship was found out, the doors of professional academia were closed firmly against him, and he would live his life with the wolves of penury always nipping at his heels.

For the next seven years, writing from the depths of poverty, he produced three works on the history of philosophy, which included a reconsideration of the epochal thought of Spinoza and Leibniz. For Feuerbach, these two figures represented a decisive turn in the history of thought: their pantheistic notions of God as a mind inhabiting or equivalent to all creation opened the way for a staggeringly rich and tantalizingly contradictory conception of God. As Feuerbach would later summarize it in Principles of the Philosophy of the Future (1843), “Pantheism is the naked truth of theism. All the conceptions of theism, when grasped, seriously considered, carried out, and realized, lead necessarily to pantheism.” And yet he believed that the unification of all thought and matter in the deity is so fraught with destructive significance that, ultimately, “Pantheism is theological atheism” – by equating God with the universe, pantheism allows humanity to see clearly that our concept of God is our alienation of our own nature; and this perception brings to a close the first stage in man’s self-rediscovery.

Dissolving Christianity

Some respite from his financial worries came in 1837 with his marriage to Berta Löw, whose wealth from a porcelain factory would keep the Feuerbachs snug and cozy until its bankruptcy in 1860. From that position of relative ease, Feuerbach launched a flurry of hard-hitting blows straight to the gut of traditional philosophy. In 1839, he renounced Hegelianism in his Critique of Hegelian Philosophy, seeing the future of philosophy not in Hegel’s abstract idealist speculation about the nature of the world as mind, but in a strictly materialist evaluation of anthropology. Then in 1841 he published his masterwork The Essence of Christianity.

This book ensures his survival in the philosophical pantheon. In it, Feuerbach painstakingly demonstrates that the attributes of God are all nothing less than representations of the species-being of humanity: God is humanity’s way of portraying itself, as a whole, to itself – an act of alienation that had to happen in order for us to overcome mere individuality, but whose time is done. As he writes: “Man first of all sees his nature as if out of himself, before he finds it in himself. His own nature is in the first instance contemplated by him as that of another being [God]. Religion is the childlike condition of humanity.” Feuerbach explains that the infinities present in the deity are the result of our own feelings of infinite potential as a collective, and the dictates of our ever-evolving reason. We survived because of our capacity for goodness, and were so pleased with that capacity that we made an ideal of it, paradoxically denying its existence in ourselves even as we hoisted it into the sky as an attribute of the deity. We denied ourselves personal goodness in order to venerate it the more, and with the passing of time actually became convinced of our own worthlessness as against the purity of God – along the way, we forgot that the very existence of goodness as a God-attribute signifies our basic goodness as a species. Feuerbach wants to remind us of what we were before we deified and alienated our favorite qualities: “You believe in love as a divine attribute because you yourself love; you believe that God is a wise, benevolent being because you know nothing better in yourself than benevolence and wisdom, and you believe that God exists, that therefore he is a subject – because you yourself exist, and are a subject.” Where Feuerbach excels is in the rigor with which he chases down each divine attribute and traces it back to its species-generated source. Even the theologian Karl Barth, who recommends that the best way to criticize Feuerbach is to “laugh in his face” has to concede that “In his writings – at least in those on the Bible, the Church Fathers, and especially on Luther – his theological skill places him above most modern philosophers” and “No philosopher of his time penetrated the contemporary theological situation as effectually as he.” And this is what you intimately feel when reading The Essence – the words of a man who has made the contemplation of religion his life’s work, offering us his dearly-bought insight into its psychology.

Dissolving Philosophy

The Essence of Christianity is a book of titanic import, filled with delectably quotable lines like, “You are terrified before the religious atheism of thy heart!” But it is only the first step in Feuerbach’s revolution. For, Feuerbach explains, philosophy freed us from the abstractions of religion only to encase our attributes in another, even more sinister, layer of abstraction. We shall not truly be free of our self-alienation, he concludes, until we slip the bonds of that philosophy.

He makes his case in the two books that followed hot on the heels of The Essence: 1842’s Preliminary Theses for the Reform of Philosophy, and 1843’s Principles of the Philosophy of the Future. In them Feuerbach starts to turn to a more aphoristic style of writing that crackles with proto-Nietzschean intensity to portray our self-knowledge as locked away from view for centuries until it was finally rescued by philosophy. At that moment, however, instead of handing it back to humanity, the philosophers took a long look at what they had in their hands and said, “You know, this won’t quite do. We’ll fix it up really nice for you, don’t worry” – and in the name of consistency proceeded to leech it of anything resembling an actual human trait. And so, in the end, we were worse off than before, because at least with God we had something for us to recognize ourselves in, whereas the idealist philosophy such as Hegel exemplified took anything smacking of a mere sensation-bound self and refined it beyond all recognition.

Feuerbach however strikes out on a new path, and in doing so he defines the project of philosophy for the next half-century: “The new philosophy has, therefore, as its principle of cognition and as its subject, not the ego, the absolute, abstract mind, in short, not reason for itself alone, but the real and whole being of man. Reality, the subject of reason, is only man. Man thinks, not the ego, not reason. Thus, the new philosophy does not rest on the divinity, that is, the truth, of reason for itself alone; it rests on… the truth of the whole man.”

Feuerbach put out the revolutionary call, and the response was immediate and fevered. Marx and Engels were among the first to answer, and although they went on to criticize Feuerbach for not going far enough in his materialism, there is no doubt that their revolutionary work is an extension of Feuerbach’s foundational concerns about the project of post-idealist philosophy.

With the failure of revolutionary reform in Germany in 1848, Feuerbach’s life took a marked downturn, not remotely helped by his hankering after the much younger Johanna Kapp, nor the ransacking of his home by police on the hunt for incendiary material. He had one more significant book in him, the hefty Theogonie of 1857, which expanded his religious ideas beyond Christianity to include classical and world religions. But with the bankruptcy of his wife’s factory in 1860, Feuerbach spent the last twelve years of his life largely a broken man, living off donations, detached from contemporary philosophical trends, and constantly ill.

In 1830 Feuerbach had thrown his professional career away with Thoughts on Death and Immortality, a book that intertwined a radical critique of religious psychology with long sections of poetry, all delivered with the rhetorical instinct of a prophet. Forty two years later, in one of the great hand-offs of history, he died the same year that a new poetry-spouting psychological philosopher-prophet, Friedrich Nietzsche, published his first work, The Birth of Tragedy. What had begun as a tentative exploration from within the teeth of Hegelianism, had, largely because of Feuerbach’s efforts, exploded during his lifetime into a revolutionary attack against the business of philosophy itself.

If we are a generation of individualistic self-obsessed maniacs, perhaps the source of both the good and ill of it can be laid at the feet of the Bavarian theologian whose life work was to, at long last, give us back ourselves.

© Dale DeBakcsy 2014

Dale DeBakcsy writes the ‘History of Humanism’ feature at TheHumanist.com, is a regular contributor to Free Inquiry and New Humanist, and is the co-writer of the twice-weekly history and philosophy webcomic Frederick the Great: A Most Lamentable Comedy.

Further Reading

Non-continental interest in Feuerbach is primarily as a linking figure between Hegel and Marx, so finding books in English dealing solely with him and his thought is a somewhat frustrating task. Mark Wartofsky’s 1977 Feuerbach is the best you’re going to find, though it is weighted towards an evaluation of his use of dialectic and other such specialized philosophical concerns that aren’t of particular interest to non-academics. So the best place to start is really with Feuerbach’s own works. Philosophy of the Future is a slim volume full of wit and punch that makes for an ideal starting point. From there, The Essence of Christianity is a natural jumping point, although I’ll caution you against the George Eliot translation, which is lovely on the whole, but full of distracting ‘Thee’ and ‘Thou’ constructions that have to be actively ignored if you’re going to make any headway with it.