Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

How Nietzsche Inspired Dalí

Magdalena Scholle looks for Apollonian and Dionysian traits in Salvador Dalí’s art.

“Even in the matter of moustaches I was going to surpass Nietzsche! Mine would not be depressing, catastrophic, burdened by Wagnerian music and mist. No! It would be line-thin, imperialistic, ultra-rationalistic, and pointing towards heaven, like the vertical mysticism, like the vertical Spanish syndicates.” Salvador Dalí, Diary of a Genius, 1963, p.17

“Yes, it is in the Spanish manner that I always sign my mad games! With blood, the way Nietzsche wanted it!” Diary of a Genius, p.40

Friedrich Nietzsche was undoubtedly one of the most controversial and influential philosophers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Among his many works, his first, The Birth of Tragedy (Die Geburt der Tragedie, 1872), deserves the special attention of art critics, because here the German philosopher introduced the concept that two opposing forces, the Apollonian and Dionysian, inspire all artistic creation. The dichotomy proposed by Nietzsche here is an attempt to interpret the world in two ways and also indicates the existence of two different concepts of truth and morality: absolute and relative.

Nietzsche’s books were read and commented upon by famous writers, philosophers and artists. In particular, the Catalan Surrealist painter, Salvador Dalí, was familiar with his most prominent works. Reading Dalí’s Diary of a Genius, we can see that he knew the contents of The Birth of Tragedy very well. The fact that here Dalí repeatedly refers both to Nietzsche’s philosophy generally and to his concept of art in particular, shows that the artist was heavily inspired by Nietzschean ideas. I wish to explore this influence in this article.

Nietzsche’s Two Spirits of Art

“The continuous evolution of art is bound up with the duality of the Apolline and the Dionysiac in much the same way as reproduction depends on there being two sexes.” The Birth of Tragedy, p.14

The Belvedere Apollo

According to Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy, art is a product of the dynamic conflict between two elements at work in culture: the Dionysian and Apollonian. He drew these terms from the names of the two gods from the Greek pantheon. It is worth noting that in the Greek tradition, Dionysus and Apollo were not considered enemies or opposing forces. But Nietzsche perceived a contrary nature in them – which seems reasonable, because these two gods embodied almost opposite personality types. Apollo was the god of poetry, art, music, and medicine, light and order, and in general, the harmony of the world. He was considered a symbol of perfect beauty, self-control, progress, balance, peace, rationality, logical thinking, moderation, and behavior in accordance with designated rules. The Apollonian attitude is well expressed by the maxims of the Delphic Oracle: ‘Obey the law’; ‘Think as a mortal’; ‘Control yourself’; ‘Control anger’; ‘Cling to discipline’; ‘Control the eye’; ‘Pursue harmony’. In contrast, Dionysus was the god of wild nature, the patron of virile and fertile forces, a symbol of a rakish lifestyle, wine, religious ecstasy, absurdity, emotions, passion, vitality, instincts, and irrationality. To Nietzsche he represents a dynamic life-giving power that breaks all the barriers and limitations established by the law, and breaks down all harmony.

Nietzsche pointed out that by following the Apollonian current in art, an artist surrenders to generally-accepted artistic principles – that is, he or she seeks to illustrate beauty and excellence through the standard formulas of the culture, and in this way, the artist is trying to beautify or idealise reality. Nietzsche was in no doubt that if an artist chooses such a conformist attitude, they depart from true nature, and even oppose reality: and the Apollonian perspective is not only against nature, it is against life and all its true manifestations. According to Nietzsche, a continual state of balance, moderation, simplicity, and order, is an illusory, fictitious vision of the world. In his view the principles of harmony, order, and perfect symmetry never dominate in nature, which is always chaotic, disordered, and variable. The desire for continual harmony comes from weakness and from a fear of real life.

Nietzsche’s concept of art is closely associated with his philosophy of life. Nietzsche often stressed that human life itself is the highest good. It is moreover a biological fact, because man is a corporeal being. Spiritual life is only an offshoot of bodily life, and a ‘disembodied’ spirituality is merely a place of refuge for the weak. Weak people need morality, inhibitions, and laws because they are not strong enough to live in the fullness of life.

Michelangelo’s Bacchus (Dionysus)

On the other hand, Nietzsche noted that the human mind is unable to grasp an ever-changing reality, because reality is not a system. So man tries to impose a framework on reality in order to organize, generalize, simplify, and inhibit nature. These actions produce a the picture of reality that is manageable, but somewhat distorted.

Nietzsche accordingly believed that the artist should not be afraid to shatter this scheme of organization. Instead, the artist should stand beyond limitations and moral schemas, should eschew the desire to escape into ideals, and should open him- or herself up to the power and dynamics of life. Nietzsche repeatedly emphasized that life’s true essence is devoid of rules and restrictions, and that this is the first and absolute truth for existence (instead of God or morality, for example). Thus the Dionysian attitude seems consistent with Nietzsche’s concept of nature. The Dionysian understanding is that the world “is beyond definition, or limitation.” The drunken worshippers of Dionysus are united with the energy of the turbulent flow of life. An artist following the Dionysian path, which is characterized by unbounded creativity, will not be afraid to push the boundaries of morality or cultural norms, and will instead follow the voice of his or her nature and impulses, which may oppose the prevailing rules, laws and conventions. Dionysian art is characteristically affirmative, dominant, irrational, and full of dynamism and internal tensions. It confirms the value of unfiltered natural impulses. It does not naïvely see the world through rose-tinted glasses. Rather, it accepts the shape of life as it is, and agrees to be bound by unknown fate. Enchantment with life, a sense of the magnificence of life, and the joy of life, are also typical, and address the need to be reconciled with the transience and fragility of human life, and the arbitrariness of catastrophe. We can say that art of a Dionysian nature genuinely speaks life’s voice. Or as a reviewer of Picasso on the website kunstpedia.com vividly puts it, the Dionysian “represents the unvarnished truth at the heart of existence: a ‘storm’ that destroys all polarity and antitheses and reveals the primordial unity at the heart of earthly existence.”

Certainly Nietzsche understood life dynamically. He believed that a person must know not only how to survive, but also how to develop in life. He advocated an attitude of conscious affirmation, breaking the resistance of the world, and sensing the growth of one’s own power. To him a person should accept reality as it is in the current moment, and experience it as best he or she can. He also had no doubt that art can influence the destiny of people. It can ennoble them, it can be a remedy for or respite from the nuisances of life, and it can help one reconcile with the drama of human existence, and with one’s fate. By practicing art we can transform the world, or participate in the process of its re-creation. In this sense, art can have a definite impact both on our lives and on the history of the world.

This is actually possible in either a Dionysian or an Apollonian way. To choose the Apollonian path is to cultivate the desire to create a perfect world, with ideal forms and classical beauty. To choose the Dionysian path is to cultivate a triumphant affirmation of life as it is, recognizing and accepting all of life, including its horrors and its darkest aspects. Although Nietzsche especially valued the Dionysian attitude, seeing in it the source of everything powerful and creative, he claimed that the highest product of society is the creative genius who miraculously merges Dionysian and Apollonian values. So although the Apollonian and Dionysian spirits seem to be in opposition to each other, their cooperation is possible. For instance, he noted that the Greeks loved beauty and admired the perfection of form, but that in this love there also lay an overflowing, formless stream of instincts, impulses and passions. And according to Nietzsche, the Apollonian and Dionysian were paired in that archetype of brilliant art, Athenian tragedy – hence the title of his first book.

For Nietzsche, the genius, the exceptional artist, would be someone who rises above mediocrity by following the strengths of life, as well as by utilising ideas of harmony and beauty. They would not be afraid to break the existing stereotypes, and would not fear to be dangerous to the existing culture. With this in mind, we can ask, did Salvador Dalí, this artist from Figueres, live up to the challenge of genius?

Another view of Dionysus

Dalí the Nietzschean Genius?

“The Nietzschean Dionysus accompanied me everywhere like a patient governess.” Diary of a Genius, p.21.

“Since Dionysius the Areopagite, nobody in the West, neither Leonardo da Vinci nor Paracelsus, nor Goethe nor Nietzsche, has been in deeper communion with the cosmos than Dalí. To grant man access to the creative process, to nourish cosmic and social life – that is the role of the artist” Georges Mathieu, from a letter reprinted in Diary of a Genius, p.171.

In the world of philosophy Nietzsche was considered a maverick, and he tragically ended up insane. Similarly, in the world of art, Salvador Dalí was seen as a problematic artist, and an eccentric.

Dalí repeatedly refers to Nietzsche’s works in his Diary of a Genius. No doubt every reader of it will gain the impression that the Catalan artist was fascinated by the philosophy of Nietzsche and with his character. He even grew his mustache to show his connection with the German philosopher (see the quote at the beginning of this article).

In his Diary, Dalí emphasizes that Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1881) drove him to atheism and the rejection of Christian virtues, and contributed to the development of his anti-social instinct and lack of family feeling. Apparently, for Dalí, the four years before his exclusion from his family were a state of extreme ‘spiritual subversion’: “To me those years were truly Nietzschean” (p.18). Dalí’s admiration of Nietzschean philosophy was so great that he called himself “the Nietzsche of the irrational” (p.23). It is also worth noting that the title of his diary suggests that the artist not only aspired to be a genius according to the German philosopher’s definition, but felt that he actually was one: “Some day… people will be forced to take an interest in my work” (p.43) or “My brain becomes normal again though I am still a genius” (p.186).

However, it is difficult to precisely pin down what Dalí wanted to suggest in claiming a connection with Nietzsche. Did he really appropriate Nietzsche’s philosophy? Or rather, did the artist behaved abnormally because he wanted excitement and wide publicity? Did he make himself out to be a madman and weirdo only for financial reasons, rather than out of philosophical agreement over an innate Dionysian impulse?

Regardless of how these questions are answered, Nietzsche’s thoughts and ideas do seem to fit well with the basic ideas of Surrealism, the art movement to which the Spanish artist belonged and loved most. One of the main ideas of Surrealism is the visual expression of internal perceptions. Artists of this style are also trying to create images that disturb the logical sense of reality. Since they cross the borderline between consciousness and dream, fantasy, or hallucination, their visions are often grotesque, and a complete move away from rationality.

In viewing Dalí’s paintings and sculptures, we can see that we are participating in thought experiments with the artist. His strange works are clearly opposed to realism, and full of dream-like landscapes and deformities. There are erotic, even lustful, threads. In his works we also often perceive an exaltation of the demonic: destruction, deformity, ugliness. There are themes of revolution, brutality, violence, cruelty, sexual perversion, and subversion. There is no doubt that the art of Salvador Dalí departs from the classical idea of beauty. In this sense, we can say that Dalí moved away from academic art, which is usually rooted in the Apollonian camp, since it refers to the human desire for order and rationality, and into the Dionysian. As Dali wrote, “That was the great lesson taught by ancient Greece, a lesson, that I believe was first revealed to us by Friedrich Nietzsche. Because if it is true that Apollonian spirit in Greece reached the highest universal level, it is even more true that the Dionysian spirit surpassed all excess and all outrage” (p.102). Certainly Dalí was a master of Surrealism and a follower of the Dionysian attitudes: “Before my life was to become what it is now, an example of asceticism and virtue, I wanted to cling to my illusory surrealism of a polymorphous pervert, if only for three more minutes, like the sleeper who struggles to retain the last fragments of a Dionysian dream” (p.21).

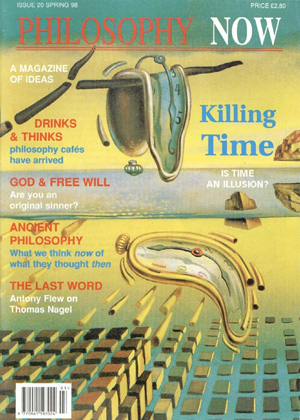

A 1998 Philosophy Now cover featuring Dalí’s The Disintegration of The Persistence of Memory (1954)

Dalí developed his own unique way of perceiving the world, which he described as ‘the paranoid-critical revolution’. This, he claimed, was a spontaneous way of generating irrational knowledge based upon the interpretive association of delirious phenomena. Yet his method explicitly refers to both the main ideas of Surrealism, and to the Nietzschean concept of Dionysian art. However, although Dalí clearly admired Nietzsche’s ideas, one cannot assume that he uncritically accepted every thought of the German philosopher. For instance, he did not like it that Nietzsche’s concepts were contaminated by ‘romantic irrationalism’: “I, the obsessed rationalist, was the only one who knew what I wanted: I was not going to submit to irrationality for its own sake, to the narcissistic and passive irrationality the others practiced; I would do completely the opposite, I would fight for the ‘conquest of the irrational’. In the meantime my friends were to let themselves be overwhelmed by the irrational, were to succumb, like so many others – Nietzsche included – to that romantic weakness” (p.19). It may be recalled that Dalí grew a mustache to be similar to Nietzsche, but wanting to be differentiated from him, he grew it into a different shape: “The important thing remains that my anti-Nietzschean moustache is still pointing to heaven like the spires of Bourgos cathedral” (p.43).

Dalí was convinced that the weaknesses of Nietzsche’s ideas were related to his mental illness. The artist also seemed concerned that he too would be suspected of some mental infirmity. As we know, the line between mental illness and artistic creativity is very thin. We can see that Dalí knew that as well, because, as he noted in his diary, Nietzsche “was a weakling who had been feckless enough to go mad, when it is essential in this world, not to go mad!… The only difference between a madman and myself is that I am not mad!” (p.17).

Through his art Dalí showed that the chaos and tension of Dionysus can always invade the sanity and order of Apollo, that beauty can always be impaired by disproportion, and that the rational understanding of emotion can be impaired by instinct, or even madness. In this way, Dalí embodies Nietzsche’s belief that the highest achievement of art is found in a synthesis of, or at least an encounter between, its Dionysian and Apollonian elements.

© Dr Magdalena Scholle 2016

Magdalena Scholle is pursuing postdoctoral research at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. She has a strong interest in the thinking of Aelred of Rievaulx and, as Magdalene Czubak, has published several books and articles on him.